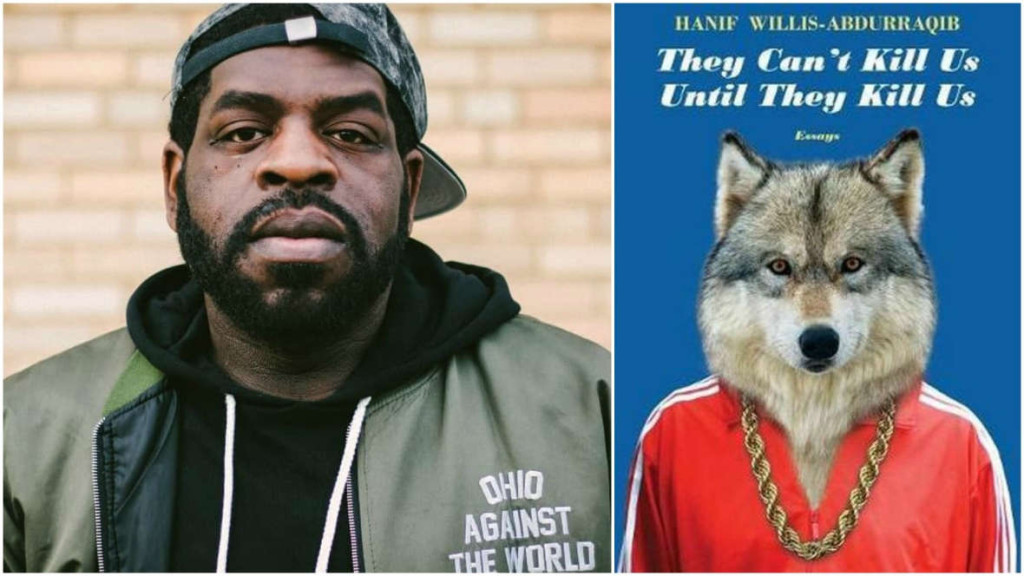

3-Minute Book Review: Paul Haney on Hanif Abdurraqib

Three Minute Book Review: Paul Haney on Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (Two Dollar Radio, 2017)

–

- If Hanif Abdurraqib’s essay collection, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, were a mode of transportation, it would be a train line. More specifically, it would be the L in Chicago, a city Abdurraqib frequents in sections of this book which navigates between the outer neighborhoods of concerts and friendships and monumental losses, and the subterranean downtown of deeply felt emotions—grief and joy, displeasure and gratitude—with deceptive ease. Let’s regard the Marvin Gaye motif spread through the book as The Loop, facilitating access to the city center, the heart of this essayist.

- Is this book papyrus, typewriter, desktop computer, or iPad? None of the above. It’s a hundred beat-up notebooks retrieved from the mosh pits, the dance floors, the stadium seats where our unflagging reviewer jots down and riffs upon his observations. Chance the Rapper, Carly Rae Jepsen, Fall Out Boy—Abdurraqib places the reader in front of the performer and commands them to see beyond the music, to glimpse the societal impact of popular performers and indie heroes alike, and how they reflect the culture that bears them.

- If you planted this book in the ground, what would grow? Hanif Abdurraqib himself, with all his insight and perspicacity. These forty essays, though mostly grounded in music, fulfill the essayistic tradition of constructing a thinking mind on the page. Readers come to know his tastes and his loves, his struggles and his successes, and they learn, too, about their own positioning in a nation whose inhabitants recognize the depths of beauty and pain alike.

Selected Quotations:

“There is no moment in America when I do not feel like I am fighting. When I do not feel like I’m pushing back against a machine that asks me to prove that I belong here. It is almost a second language, and one that I take pride in, though I wish I did not need to be so fluent in it. I know what it is to feel that urge to build a small heaven, or many small heavens. Ones that you cannot take with you, but ones that cannot be taken from you. A place where you still have a name. I believe, at one point, that Marvin Gaye looked at a country on fire, and wanted that for us all” (p. 99, “III”).

“For anyone who has ever loved someone and then stopped loving them, or for anyone who has stopped being loved by someone, [Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours] is a reminder that the immediate exit can be the hardest part. Admitting the end is one thing, but making the decision to walk into it is another, particularly when an option to remain tethered can mean cheaper rent, or a hit album, or at the very least, a small and tense place that you can go to turn your sadness into something more than sadness. It’s all so immovable, our endless need for someone to desire us enough to keep us around. To simply call Rumours a breakup album doesn’t do it justice. Most breakup albums have an end point. Some triumph, a reward or promise about how some supposed emotional resilience might pay off. Rumours is an album of continual, slow breaking” (166, “Rumours and the Currency of Heartbreak”).

Paul Haney’s work has appeared in Fourth Genre, Sweet, Essay Daily, Slate, the Boston Globe Magazine, and elsewhere. While earning his MFA from Emerson College, he served as Editor-in-Chief of Redivider. Now he lives and teaches in Boston, where’s he’s writing a Bob Dylan bibliomemoir. Follow him @paulhaney.