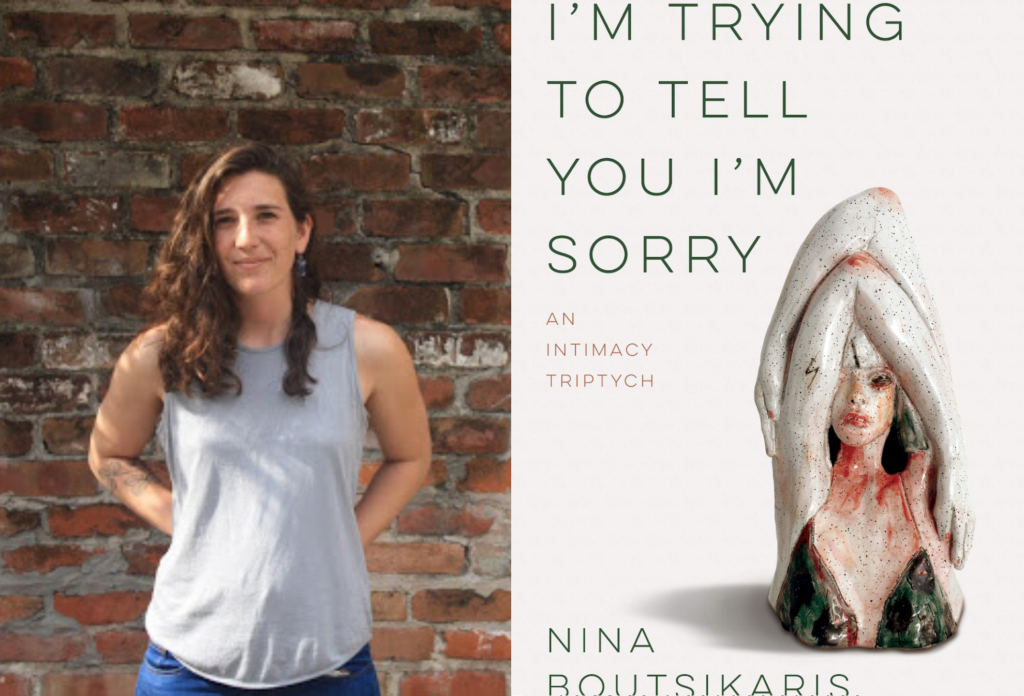

“What I mean is”: On Nina Boutsikaris’s I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych

“What I mean is”: On Nina Boutsikaris’s I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych

Austyn Gaffney

New York: Black Lawrence Press, 2019. 140 pages. $16.95

Nina Boutsikaris is a sieve. What I mean is, in her first book, the memoir I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych published by Black Lawrence Press, words leak from Boutsikaris — words on family, fragility, art history, good sex, bad sex, desire, abuse, fidelity, friendship, theft, manipulation, friction — and they plink across the pages. She filters her experiences, and runs her hand beneath them to see what sticks. It’s this stickiness she communicates to the reader.

What I’m saying is, her book is a fly trap. Husks of past lovers and parents and friends and selves. She collects these husks to try and understand men and power and how they’ve cased her. It’s framed as a triptych, looking not only at herself but how the world looks at women. She uses art as a lens, reflecting on a painting (“Man Greeting Woman” by Ken Kiff) where the orange blob of a man tips his hat toward a woman leaning into a lawn. Both are naked. Heterosexuality is performative. The greeting, the feign of desire, the invitation are performances.

“Maybe it has never been me looking at myself,” says Boutsikaris. “Where or how could I even begin? A man is greeting a woman. And so she is naked in a field.”

What I’m trying to say is, she’s looking at the relationship between men and women. She identifies herself as Derrida’s printer: archivable meaning is determined by the person who archives. She fingers the soft spots around her world like an orange. She holds out her palm to us — open and addressing: how did I get to be this way? Who is this person leaking confessions like plucked citrus? And whose fault is it? Men have been the printers of women. How can I undo the ink?

Let’s just say, Boutsikaris’s book is a series of reintroductions, of pretending the new place she begins from is somehow less tethered to the place she just abandoned. And when that explanation doesn’t seem to do her meaning justice, she doubles down with repeating phrases (plink, plink, plink): “What I’m saying is… what I’m trying to say is… what I mean is… let’s just say. Maybe — here’s what I mean — I’ll start over.”

In the beginning, it is difficult to know exactly whom Boutsikaris is writing to. At first it seems it could be a parent. Then a lover. Then perhaps, a partner, who is trying to understand her past. Eventually, it seems it is the society that has reared her. But by the end, I wonder if Boutsikaris is just writing to herself.

“What I’m saying is I tried hard to make it okay,” she says in “Be My Nepenthe,” her triptych’s first section. She’s with a man who flew her to Miami for the weekend. An extravagant gesture that pushes Boutsikaris to feel outside her power in relation to men, social function, herself: “Meaning that night I had to do what I had to do. To be gracious, to at least try. It was among the less easy encounters. I really had to will myself not to think thinky thoughts about objects and subjective investments, about spectacle and the big, black void between us, the melancholy in the reification — thoughts that made me sad because I knew I could probably never unthink them; that there was no going back.”

She invokes nepenthe, or something aiding in forgetfulness, especially of grief or sorrow, and in pleasure. How sex and flirtation and fleeting companionship can help us forget our childhoods or our ostracizations or our loneliness. As the printer, she needs others to need her. To help her create meaning. She is aware of the sexism that frames her relationships — a man invites her to Miami for sex, a man demands she smile, a man outside a bar tells her to grow a bigger ass, then claps! — and yet she finds a version of identity here, like a piece of tangerine.

She uses the section to deconstruct herself: “Was I ever not afraid of men? / Meaning did I ever not fear that they would and would not? / Meaning I spent a lot of time sneaking around. / Meaning I still do. / What I really mean is I wanted them.”

At 14, boys she’s never met show up at her front porch. She doesn’t know how they find her address. They invite her to parties. She demures, and after a few attempts, they leave. She wonders if that was the right choice. She lost the power of being the thing they wanted — the nepenthe. Still — who are these boys who come knocking? How did they find her? How did they know what they wanted to ask and that they could? Who taught them? Later, a boy screams slurs at her at a party. When she gets angry, shouts back, the room turns on her. Who is she to show anger? “Because it was my anger, don’t you see, that had caused the trouble,” Boutsikaris reflects. “For a long time I held my keys between my knuckles when I passed that house.”

Her interrogation brings us out of nepenthe, her hinge back toward power. How to get out of powerlessness? Control. Learn how to control men, and then, her own body. In the second section, “This One Long Winter,” Boutsikaris is sick and living in New York City. She finds lovers. A woman with whom she filches purses. The “nighttime boys” who comment on her body, which is sickly and shrinking, and name it: beautiful.

She visits a clinic with regularity. She wants to know what is wrong with her. In the waiting room, a woman tells her to move towards softness. “Are you ever going to stop being someone else… All around you is softness, waiting.” Boutsikaris is growing up and reckoning with who she has become. Nepenthe showed the reader what series of experiences moved her here. Now the printer wonders what will move her past here. “Where is my softness,” Boutsikaris repeats. Plink, plink. “What kind of girl am I?” She maintains control by controlling a body, a set of reactions, a cold exterior. Until it cracks.

In the third section, Boutsikaris moves outside of the city to the desert sun. She meets different men, and begins asking who is stuck to her: “What I mean is how can I know what I have done? How can I know which processes I have been to whom — collecting, impermanent, on some already fleeting surface… Who is inside me forever?”

If you identify as a woman, who has ever slept with a man, you may see flashes of yourself here. Little clips from the clicking film of your escapades into late night pleasure, like when a thumb or a thigh pressed just so, but more likely from all the things that may now, or later, feel grimy. Seconds, if sheared from your life, you would not miss: “This is what these boys liked,” Boutsikaris recounts, “what they did with their bodies. I had no choice.”

Like the times you had sex before you knew what it meant to be wet. The times at the drug dealer’s house when the sporadic knock on the door sent him from your stomach to the lock box inside the closet. The times someone threaded past your waist while you counted change at the register of the fast food restaurant and you wished they both would and would not. The times you slipped aside your lace underwear, gave the blow job, slid your hand down, though your mind felt hazy. The times you said yes but shut your eyes. The times he slept off his orgasm and you, still untouched, rolled back and forth wondering how you’d survive the lonesome night. How foreign and intimate your body was then, when under someone else’s hands, you felt no tether to the act. If you’ve ever slept with a man, and felt any version of that, Boutsikaris will scream to you, and you might find yourself screaming back.

For her final pages, Boutsikaris stands in front of a man she finally feels kindness toward. She is wanting, but she is in her power. She holds the trigger of a gun and shoots it across the Arizona desert. “It was just a posture,” she says of the act, “it was like anything else.” Boutsikaris is posturing. She’s performing. Her book is a performance.

“There’s no real end to writing about your own life,” she says. “Only segments of examined companionship that by necessity come to a close. What that means is the possibility of redemption continues beyond the last page. Forgiveness maybe… As if writing it all down was enough of an apology, a good excuse. As if being the recorder could make anything forgivable, make anyone lovable. I get it. I do.”

By the end, she has found a sort of salvation. She returns to art, quoting Marina Abromovic’s vision of herself as three unique people: a triptych. It’s hard to know if Boutsikaris forgives herself. Her voice is confessional, but it’s also on loop. It is a mixture: the things we want and the things we’re taught to want. She finds clarity and digs deeper. Finds clarity and digs deeper. Plink, plink.

Once I biked over a bridge just north of Savannah where marshland met river and then met sea. The water swooshed like milk tea. Sediment and salt formed a brackish line. Boutsikaris’s book is that line. Two opposites from the same source meeting: our desire and our displeasure. Our transparency and our mystery. Boutsikaris stands in that whirlpool. She looks around, collects the detritus, reports back: we are all three things — the flesh, the salt, the brackish between.

What I’m trying to tell you is, I was glad for her labor. I was glad I met her here.

Austyn Gaffney’s stories appear in Blue Mesa Review, where it was selected by Leslie Jamison, Brevity, HuffPost, onEarth, Prairie Schooner, Sierra, Vice, and elsewhere. She has received funding from Bread Loaf Environmental Writers’ Conference, Brush Creek Arts, the Kentucky Arts Council, the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources, and PLAYA. A graduate of the University of Kentucky MFA program, she now lives in Louisville, Kentucky.