Review of Rosalie Moffett’s “Nervous System”

By Amie Whittemore

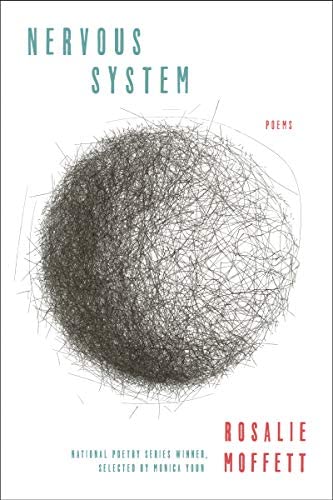

Moffett, Rosalie, Nervous System. National Poetry Series, Ecco Press, 2019. $16.99

Analyzing the brilliance of Rosalie Moffett’s second collection, Nervous System, feels a bit like trying to limn a spider’s web, for it is as pliable and delicate, smart and inventive as a web, releasing light as it acquires a feast.

The collection consists of two poems—a brief opening poem, “What the Mind Makes,” and the long title poem, “Nervous System,” makes up the remainder, though it is divided into parts, titled by first lines. Nervous System contains a singular preoccupation: the speaker tries to make sense of her mother’s disintegrating memory, and through this exercise, engages with multiple components of self and non-self, of home and away, of heart and mind, of inheritance, of spiders and snails and the electricity humming beneath it all. Woven from tercets, which exemplify the speaker’s uneasy search for clarity, these poems query the world, never feeling fully satisfied with what they find: every feast these marvelous webs catch, reveals another appetite.

“What the Mind Makes” sets up the spokes of the book’s web:

my memory grows, rising dough, it self- / fabricates, zooms // out to include in the frame the necklace / of cars fleeing the storm, / child-me asleep in one glinting bead. // These images arrive, file / themselves in the folder with the others / marked mother.

Here, the motifs that will haunt the collection are introduced: the speaker’s concern with her own memory in juxtaposition with her mother’s fading one; the multiplicity of self; and the desire for image to cultivate meaning. The poem closes with a wish: “there is a bit of faith // in what the mind makes / for itself, isn’t there?” Nervous System is a collection premised on faith—the faith of connections that defy and reify memory, the faith that language might provide us with all we ask of it, despite, or because of, our fears of how fully nestled our sense of self(s) is within it.

While these poems harbor nervousness, this sense of nerve is always multiple: the poems are nerveless and nervous at once. For instance, in an early section of “Nervous System” titled “[Scientist’s betrayal],” Moffett writes, “fear my mother would forget me, one copy / of my self deleted, // leaden shape / in her mind / where I once was.” Here we see that the mother’s memory loss is also an existential threat to the speaker: what do we become when our parents no longer recognize us?

However, this fear, while not erased, is, perhaps eased by what actually happens between the speaker and her mother:

she made two of me—twins, of which / only I survived, which is why / she doubled me again // every time I left the house, / saying, Take care of Rosi, as if one of me / could watch over another of me.

Here, the tatters of memory create a kind of satchel—the mother creates a stand-in that reassures the speaker of her own strength through this slip of memory: “little perfections exist,” the speaker notes, and “it is possible // to be content / like this.” This sense of the mother as a precarious cradle, is repeated in “[Her blood so thin when they drew it,]” when the speaker considers the “pain-only traffic” in the nerves, and how, when trying to interpret a dream of spiders as a sign of conflict with the mother,

the brain waves like a flare, a little request / for venom, a little / like my mother: her blue arm, her self // which held my self, idea / of me, until it was real.

Again, the speaker expresses concern that her identity is staked to her mother’s, that even as these poems seek to reconcile the cohabitation of loss and self, the idea remains unbearable: “it’s hard for me to believe // in anything / that hasn’t been made / into something else,” Moffett writes in “[Perhaps it wasn’t her head hitting the rocks.]” The transformation of grief into poetry, the transformation of experience into language—these transformations are, despite their fluidity, the only stabilizing forces the speaker trusts. This truth the speaker discovers suggests the transformation of the mother from one version of herself into another must also be embraced, held among the other, often unsought, changes in life.

Thus, while this collection is anchored by grief, it is buoyed by awe in the world, the self, the complexities and, thus, marvel, of being alive. In “[it’s not one spindle, one spool of thread,]” Moffett writes, “How easy it is to miss this / world we’ve been allowed into,” as the poem’s speaker admires the “remarkable factory” of a spider’s spinneret.

Nervous System is as much a remarkable web as a snail shell—the poems bring in more and more of the world as it spirals toward its close. For instance, admiration for the world gives way to longing: “what we want is to feel // like we’re wearing nothing, wanting / for nothing,” Moffett writes in “[In the event of a fly or beetle thrust headlong],” a poem that interrogates human desire to use spider’s silks for “bulletproof / body armor.” But, the spiders can’t work under the conditions that would make such transformation economically viable (thankfully), and here the poem presents a kind of solace: no matter how “exceptional” many humans feel about humanity’s place on earth, we cannot bend everything to our will; we must be humbled by our own fragility, by our tattered wiring, our fading memories. The human brain, this dazzling electrical storm, this folded collection of canyons that is heartbreakingly able to feel a part of and apart from the world all at once—this aching liminality is the geography these poems inhabit with tenacity and grace.

Amie Whittemore is the author of the poetry collection Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press), the 2020-2021 Poet Laureate of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and an Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellow. Her poems have won multiple awards, including a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Prize, and her poems and prose have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Nashville Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere. She is the Reviews Editor for Southern Indiana Review and teaches English at Middle Tennessee State University.

Rosalie Moffett is the author of Nervous System (Ecco Press) winner of the National Poetry Series, chosen by Monica Youn. She is also the author of June in Eden, winner of the Ohio State University Press/The Journal prize. She has been awarded a Wallace Stegner Fellowship in Creative Writing from Stanford University, the “Discovery”/ Boston Review prize, The Lorraine Williams poetry prize from Georgia Review, the Ploughshares Emerging writer prize, and scholarships from the Tin House and Bread Loaf writing workshops. Her poems and essays have appeared in Tin House, The Believer, New England Review, Narrative, Kenyon Review, Agni, and other magazines, as well as in the anthology Gathered: Contemporary Quaker Poets, and The Familiar Wild: On Dogs and Poetry. She is an assistant professor at the University of Southern Indiana.