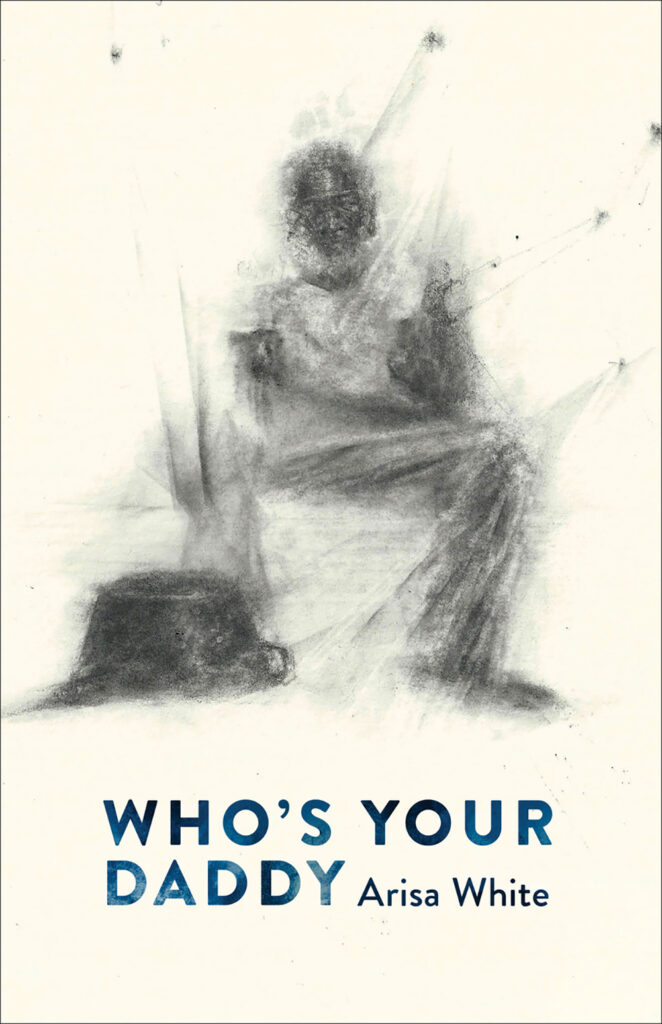

Exploring Repetition, Renewal, and The Cycles of Time in Arisa White’s, “Who’s Your Daddy?”

White, Arisa, Who’s Your Daddy?. Augury Books, 2020. 138 pp. $16.95

By Briana Swain

What happens when you discover a question that must be unraveled throughout a lifetime? Each time it arises the associated consciousness of the question and the question asker shifts. Just as a cloud never retains the same shape yet floats as the same cloud, the answer exists as an ever-changing state of being. In Arisa White’s newest collection, Who’s Your Daddy?, she presents an epic journey of question asking that constantly renews itself in the ultimate pursuit of health and healing.

Who’s Your Daddy? is an autobiographical exploration of how the absence and presence of various fathers and figures of fatherhood created the larger subconscious framework that Arisa, the female speaker, derives her decisions and experiences reality from, and ultimately, desires to heal from. White utilizes prose, poetry, and memoir to sharpen the emotional and spiritual journey that encompasses mining her family mythos to recreate a narrative of renewal and freedom that reflects a truer sense of self. By engaging in the healing practice of unwinding memories, reconnecting with her father, and traveling to his place of birth, the speaker evolves her understanding of the past for reconciliation and acceptance.

Divided into four sections punctuated by Guyanese proverbs—a head nod to the poet’s ancestry and one of the grounding pillars of the text—this journey begins in high lyric while the narrative arises like waking from a dream, slowly and then all at once. There are no clear demarcations of poem by title or page; instead they are notated by bolding each beginning phrase. The timeline begins with a childhood that reinforces and establishes the speaker’s reconnection with her biological father later in adulthood. As someone that originates from a lineage of absence, my maternal grandfather died before I was born and I have only met my living paternal grandfather once as a toddler, I find one of the most defining features of this work is White’s description of trauma and Black fatherhood without reproducing troubling narratives.

One instance of White’s resistance of trauma narratives is located within the poem “Gerald calls on June 14.” The speaker recalls a telephone conversation with her father where he asks what she’s getting him for Father’s Day after only exchanging a letter and Skype call since before their estrangement. After laughing and telling him no, the speaker asks if “[his] feelings are hurt” and allows his emotions to coexist amongst hers as equals, two people experiencing the depth of years of awkward silence, newfound acknowledgement, and hurt. Instead of becoming distracted with the speaker’s internal experience and projecting it outwardly, White focuses on the dialogue between the speaker and her father, adding in observational details that only heighten the emotionality like noticing background noises, naming the experience and dynamic between the two without analyzing it. She allows the moment after they say goodbye—when the speaker’s father curses before his phone has turned off—to linger as our final moment.

What White describes in the opening poem “Prologue” as a “grandfather feeling” buzzes in the background waiting to become fully realized. This collection is a coming of age narrative that expands beyond linear time, constantly informing itself along the way. White establishes a self-referential text by infusing elements of time together, using repeating imagery and symbolism, and expanding the reader’s understanding of past events as the speaker gains more understanding of herself and her father. A moment I experienced a nonlinear expansion of time most poignantly is in one of the beginning poems “My mother is nineteen…”

All the places she goes. In his Cadillac down Fulton Street,

down Nostrand Ave, without question up and down Atlantic and

Pacific, DeKalb, on Eastern Parkway, through Gates and Myrtle,

Bushwick and Halsey, sunsets on Jay. Down this first day of

spring, red lights every two minutes when contractions start. The

cab ride stretches out before the hospital.

This poem oracles the rest of the collection, exposing how various portals exist within one moment. The beginning line “My mother is nineteen when she meets Gerald,” situates us in a past that leads into the future, which seemingly displays a western understanding of time. Yet, through this memory the future exposes itself within the past and present. Located in the memory of when Gerald taught Denise how to drive, the adult speaker ruminates on being Denise’s second child while in the womb, and Denise begins feeling birth contractions. This allows us to register a more expansive awareness of the speaker’s humanity, that she exists beyond the limitations of family, sexuality, gender, history, and her own perceptions.

Immediately, I hear how Robert Lashley’s The Homeboy Songs extends itself as a cousin to this collection as both poets articulate how the voices and energies of their many lineages, seen and unseen, inform a poetics of Sankofa. Embedded in these texts is a revisioning of poetic modalities rooted in Black and African consciousness that decolonize the psyche allowing them to dream and evolve past current systemic restrictions on bodies, communities, and perceptions of being. A few notable ways White achieves this is through movement of time and people. White displays transparency of her influences via quotes, notes, and passages from authors and musicians like Erykah Badu, Alaine de Botton, and Henry A. Giroux. There are offerings of memory and the subconscious, rituals and cues that suggest we are entering into different realities that either recur or can be tracked via dream signs and/or dream iconography.

These poems begin in the womb, not the womb of a physical body, but an ancestral energy that is nurtured and exposed while the speaker births herself. Moving left and right, diagonal and straight, between the cosmos and Earth in the poem “I walk with a poet friend around Lake Merritt,” this speaker is “starting from the east and then returning east.” A similar logic is found within Sasha Steenson’s The Method. Steenson uses Archimedes’ historical text of the same name and the various ways it’s survived through history as a vehicle to grapple with the relationships between people, their histories and written work. The resonance between these writers occurs in exposing the crude methods of preservation that affect societies and culture. They understand how societies withstand trauma, absence, separation, theft, and forced migration in ways that change us for survival. Alternatively, the speaker begins her journey when she realizes these methods must be abandoned when they oppress or inhibit her expansion. Through this collection, the speaker guides us through Guyana, a physical and ethereal family history, romantic and familial relationships to find out what is there if “The Father isn’t the answer.”.

This collection isn’t just about fathers, but also about exposing where fault lines and resulting tensions exist. How, as White states in the poem “It’s our last full day in Guyana and we wake at 5AM…” we begin “to feel the pull of earth opening up” when we realize that “there’s no contact between human beings that does not affect them both.” Alternatively, I can only begin to grapple with healing when I acknowledge another person and allow them to touch me with their humanity and vice versa. At this moment in the collection, I am able to feel a lesson of liberation most tangible, when I expand my stomach with air in gratitude.

Although there’s unyielding energy that pulsates in the climax, the real juice is in the speaker’s journey. During all of the build-up, the expectation, the curiosity, a question I found myself asking was what does it feel like to really be here in this world in my body, and how might I embody that in my writing? White understands that the end result is only as potent as the work it takes to carefully discern what the journey points to and build up to it. White offers the opportunity to pay attention and integrate instead of continuously reacting and responding to what is observed as what we observe is only as vast as our perspective is. Who’s Your Daddy? is a reminder of what lies beneath superficial truths, how creative and ripe the subconscious is, and what begins to unfold when healing is given the time, attention, and space it deserves.

Briana Swain believes in herself and the power of her words. She received her MFA in

Creative Writing from Saint Mary’s College of CA and Theatre BA from CSU Sacramento.

She writes to envision new manifestations of Black consciousness, subvert the colonial gaze,

ascend possibilities, and exist in humanity as a site of liberation for the African Diaspora.

Swain has received scholarship to The Juniper Summer Writing Institute and is published in

Pleiades. She currently lives in Sacramento, her hometown, extending her creative practice

beyond a degree and into the hands of the people.

Arisa White is a Cave Canem fellow and the author of Who’s Your Daddy and co-author of Biddy Mason Speaks Up, the second book in the Fighting for Justice series for young readers. Nominated for a Lambda Literary Award, an NAACP Image Award, and a California Book Award, her poetry has won the Augury Book Prize, the Per Diem Poetry Prize, the Nautilus Book Award, and the Maine Literary Award. Professor White is the recipient of fellowships from Headlands Center for the Arts, Squaw Valley Community of Writers, and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. She serves on the board of directors for Foglifter and Nomadic Presses. Professor White attended UMASS, Amherst and focuses her work on poetry, the hybrid memoir, middle-grade verse, short-form playwriting, and choreopoem. More information can be found at www.arisawhite.com.