ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: “Mother Goose” by Jenee Skinner

Read an interview with the author here.

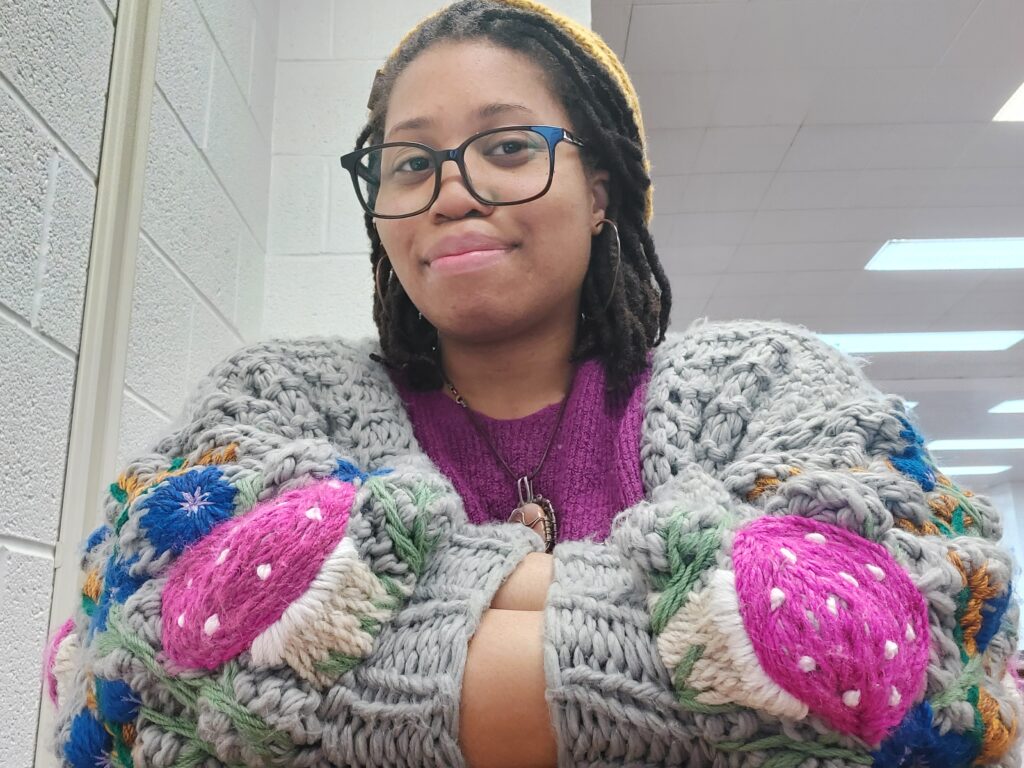

Jeneé Skinner

Mother Goose

An old woman gave birth to four eggs. Gold and cradled by tree roots and ribbons inside her house. Their births were ugly, complicated by forceps and fluorescent lighting, but the loving made it worth it. Their father was more forest than man, belonging everywhere and to no one. He invited her to his pond where they swam in moonlight and she tasted a whole other world on his tongue, all the things she didn’t know about redlining, recycling, and the prison-industrial complex. Before she could ask what was the best way to end lending discrimination and what plant-based materials could replace plastic, the man kissed her. Then he squatted on her back, bit into her neck, spread his arms wide as if he and she would fly the night away. The old woman bit her lip as he slid his fingers over the moles of her cheek and taught her how to make love.

*

An old woman gave birth to four eggs. The eggs reflected like a lighthouse at night, smiled with the sun during the day. Predators masked as suitors approached and knocked on her door. The first was a garden snake who wrapped perfectly into the curves behind her knees and elbows. She missed being touched so much that for a moment she closed her eyes. That was all it took for the snake to swallow one of her eggs, a torch-like shimmer sliding down his throat. What the snake didn’t notice was that the old woman’s neck was shaped like a river, with enough bends and length to kill him. In an effort to recycle, she stretched the snake’s scales and organs out, weaving them into the nest of her remaining eggs. Though she tried to pump the snake’s stomach for her lost egg, all that came up was some leftover yolk.

On the nights when the rat, dog, raccoon, and crow came for dinner, the old woman was ready. First came their smile and conversation, then their hunger. None of them ever suspected that she was hungry too, that she craved flesh, not just for her lost child, but to feel desired, to be reminded that she was a woman before she was old. Their paws, wings, snouts momentarily smoothed out her wrinkles when they embraced, but her eyes stayed open and her neck stayed sharp.

The fox’s tongue was the most cunning, his eyes the most familiar. It wasn’t until after his teeth went for her throat, after her neck wrapped around his, after her teeth crushed his jaw that she recognized he was the father of her children. Pulling off the fox’s clothing, the old woman saw her beloved’s eyes, human, round pupils instead of slits. Despite the night he made her feel like she could fly, he tried to consume what they had made, when she would’ve happily shared her riches if he’d asked or just stayed. She vowed to spend as few tears on him as needed, then lined her children’s nest with his body as she’d done with the rest. By the time the police knocked on her door and questioned her about her beloved’s disappearance, her goslings had already hatched and made a meal of him, not even sparing the bones. It made her happy that her children had been close to their father in some way and that his body gave back to the community they cared so much about.

*

An old woman gave birth to four eggs. The remaining three hatched, blessing their mother with a few years of chirps, soft down feathers, and need. But their youth was a race that ran faster than the old woman was ready for. Soon they waddled out of the house. One joined a gaggle of geese, choosing a simple, traditional life dictated by weather. The second spent his days going to marshes and lakes, trying to chase moonlight, the same in which his parents conceived him, until a wolf snatched him up for dinner when he got too close to shore.

The third child stayed with the old woman longer than her brothers because the world beyond the porch was terrifying. The old woman knew it was selfish not to push her daughter out of the nest so she could know the beauty of falling before flight. But a mother’s biggest betrayal was an empty nest. How thankless it was to spend years giving others wings only to be trapped on the ground alone afterwards. Besides people treated the world cruelly. Shrinking the forest that fed life, cutting down its trees, poisoning its waters, banishing its creatures to highways and backyards. All to house an economy that devoured people as much as it did land. Keeping her daughter out of the city’s smoke-filled mouth was the responsible thing to do. So she fed on the girl’s ignorance, tasted the golden edges of her hair, which still held the aroma of eggshells. Every time the old woman looked into her child’s eyes, she saw her beloved, doting and at peace, and knew she made the right decision.

One day while the old woman took a trip to the valley to pick roots for dinner, the house flooded with river water. Not knowing how to swim, the daughter flailed and sank to the bottom, the odor of decaying wood filling her throat. A mud cat swam through the door, silver-bellied and basil-colored muscle gliding through each room like oil. When his whiskers brushed along the young woman’s face, he tasted her freckles and innocence. He smiled and opened his mouth wide as if he could swallow the room. She hesitated and looked around the bony crevices of his cheek, but realized that his skin was the only thing that contained air and swam in. The mud cat burped a bubble that cocooned her head and made her gasp as if being reborn.

He swam through the forest with her on his tongue, showing her all the stories the forest held: when butterflies land on turtles’ noses, why the bobcat’s mane was shaped like pine tree needles, how moss came to grow on moose antlers. He showed her the joy first to balance out seeing the forest’s pain. The polluted mine water that made fish taste like zinc, bald spots filled with cement roads where trees used to be, children scrapping parts from cars and e-waste at a local junkyard. The mud cat’s knowledge touched the young woman like a solution, a seduction of hope that made her want to be in the world to heal it. Mistaking enlightenment for love, she swam out of his mouth and kissed him, let his whiskers wrap around her waist because she wanted to know more of him as well.

The old woman came back to a soggy house that reeked of mildew for the next week. The roots spilled on the floor once she noticed her daughter was missing. The young woman showed up an hour later with a smile and a necklace of small ruby-colored beads. Seeing the mucus remains of fish around her daughter’s chest, the old woman tried to snatch the beads off, only for the child to slap her hand away. Apparently, her daughter’s world had grown bigger while she was gone. Over the next few months, the beads around her neck blossomed to bulbs with forming bodies inside. Her daughter left in the middle of a few nights, wet and shimmering in starlight, no explanation of where she’d gone.

When the bulbs were the size of plums, the young woman went out to reunite with the mud cat only to be knocked unconscious in a bed of dirt. When she woke, her necklace was gone and she smelled of decaying wood. Though she could still feel the fish’s whiskers along her neck, a part of her had been stolen. When the old woman held her daughter and tears fell on her shoulder, she smiled having seen the mud cat swim off with a necklace of eggs from a distance. Sometimes when she was in town, she’d look into a restaurant and see a well-dressed couple eating roe and wonder how her grandchildren tasted.

Her daughter’s grief didn’t keep them together as the mother hoped. Instead, it gave the young woman the wings she needed. She left the house, traveling around the forest collecting more stories and telling them to children. Fairytales where ecosystems were both heroes that protected and princesses that needed protecting. Fairytales where boys listened and girls learned. Along the way, she met my father, a clean boring man who was safe and never left. They married and had me, a vessel to hold my mother’s stories and know the world before a suitor, man or beast, tried to teach me.

*

An old woman gave birth to four eggs. But when they were gone, there was nothing but dust and her children’s feathers to keep her company. She grew fat with age. That way there’d be more of her to notice, more of her to fill the space that her beloved and children once did. She went out for late-night swims and drinks and dancing, but remained lost.

Years later, two businessmen knocked on her door and offered her a check for her land. They told her they’d make the forest better than itself, better than the air that flowed from trees, by building shiny new coffee shops, parking lots, and yoga studios. And of course, they’d make the nest of her golden eggs a tourist attraction to complete their gentrification. Of course, they didn’t call it that. Though she doubted their intentions like every man before them, there was nothing tying her to her home anymore. While she didn’t want her land and its creatures to be displaced, her home had gone years ago with her children.

After the men laid the check in her hands and left, the old woman accepted that’s what she wanted. To leave. She gathered the few remaining feathers that had fallen into the nest over the years, but they weren’t enough. So she went out and searched the ground for all the discarded Styrofoam, aluminum, paper wrappings, and plastic containers she could find. Once all the items were cut into strips, she stitched together a set of wings and attached them to her arms. With arms she’d held countless love and loss, with wings she would hold herself. She flew for years, looking down to find a place that had room for her as no man, beast, or child had. Eventually, she looked up and saw the point where earth and sky met and knew that’s where she’d reside.

*

I’ve gone to the forest a few times, hoping its presence would tell me if I’m more animal or woman. Every time I talk to the flora and fauna, they tell me I’m too young and don’t have enough stories to fly on yet. I try to catch sight of my grandmother in the horizon. Searching the sky, asking the birds and fish if they’ve seen her. Sometimes I’ll see a shadow the size of an angel ruffle between the trees, but when I run towards it, only a feather floats toward me. I’ve started gathering litter off the side of roads determined to turn trash into wings as she did. One day I hope to transform the earth’s waste into its salvation, but for now I’ll settle for getting up to the horizon. If during sunrise or sunset you happen to catch an old woman flying outside your window, tell her to come see me. I’m trying to figure out which of my mother’s stories are fairy tales and which are real.

Jeneé Skinner has a degree in Creative Writing and went abroad to the University of Oxford to study Renaissance Literature and the Italian Renaissance. Her work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, Missouri Review, Roxanne Gay’s The Audacity, and elsewhere. Additionally, she won Michigan Quarterly Review’s Jesmyn Ward Prize and was a finalist for the Black Warrior Review’s Fiction Contest. She has received fellowships from Tin House Summer Workshop and Kimbilio Writers Retreat. Her work has been nominated for Best Microfiction, Best of the Net, and a Pushcart. She’s a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. You can find her on Twitter @SkinnerJenee or Instagram @jskin94.

Jeneé Skinner has a degree in Creative Writing and went abroad to the University of Oxford to study Renaissance Literature and the Italian Renaissance. Her work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, Missouri Review, Roxanne Gay’s The Audacity, and elsewhere. Additionally, she won Michigan Quarterly Review’s Jesmyn Ward Prize and was a finalist for the Black Warrior Review’s Fiction Contest. She has received fellowships from Tin House Summer Workshop and Kimbilio Writers Retreat. Her work has been nominated for Best Microfiction, Best of the Net, and a Pushcart. She’s a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. You can find her on Twitter @SkinnerJenee or Instagram @jskin94.