ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: An Interview with Jeneé Skinner

Osasere Edo-Ewansiha

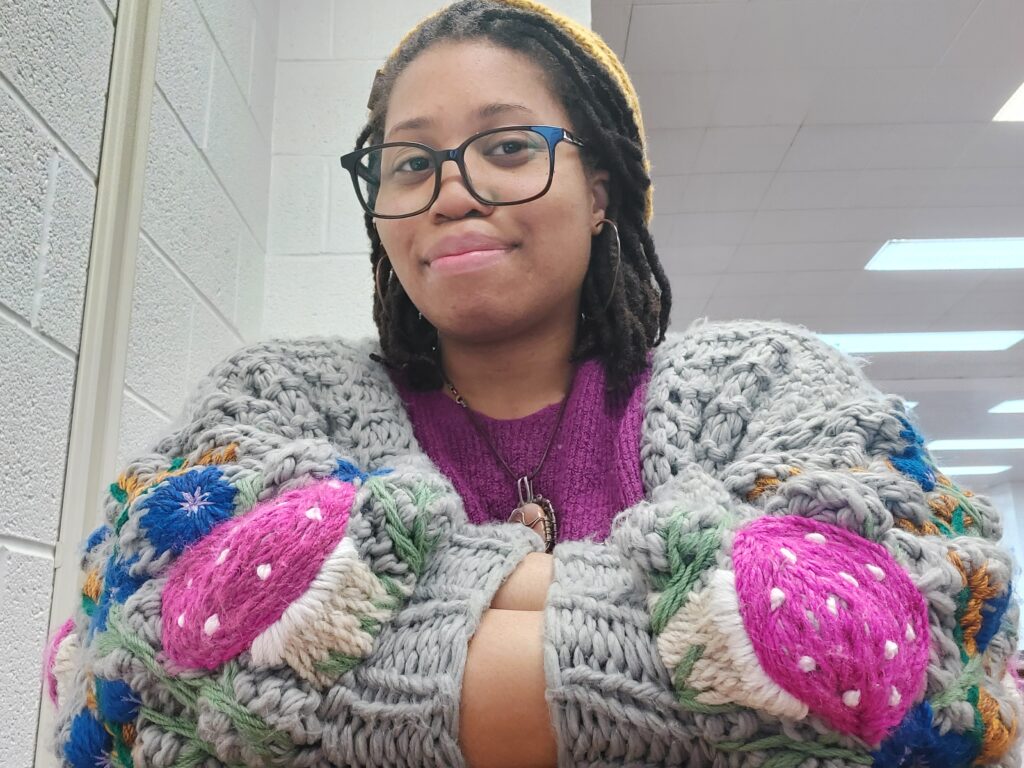

Jeneé Skinner

Jeneé Skinner has a degree in Creative Writing and went abroad to the University of Oxford to study Renaissance Literature and the Italian Renaissance. Her work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, Missouri Review, Roxanne Gay’s The Audacity, and elsewhere. Additionally, she won Michigan Quarterly Review’s Jesmyn Ward Prize and was a finalist for the Black Warrior Review’s Fiction Contest. She has received fellowships from Tin House Summer Workshop and Kimbilio Writers Retreat. Her work has been nominated for Best Microfiction, Best of the Net, and a Pushcart. She’s a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. You can find her on Twitter @SkinnerJenee or Instagram @jskin94.

Why did you decide to use references to fairy tales as a vehicle to comment on present-day concerns such as environmentalism, feminism, gentrification, and more?

I’ve been attracted to how succinct and confident fairytales are. They don’t shy away from the horrors, tragedies, or lessons that make up reality. Yet there can also be room for happy endings, or a character winding up somewhere that’s better than where they started. All of it reflects the better and worse aspects of humanity. Fairytales don’t explain themselves. They just happen and allow the reader to process the events in their own way.

“Mother Goose” was created image by image and leaned into moments of the characters’ strength, vulnerability or curiosity. It began with my wanting to put my grandmother into words. Or at least design a woman who could converse with my grandmother. I hadn’t seen fairytales about older women who weren’t witches or crones. Plus, I’d heard a lot about Mother Goose (MG) as a famous storyteller and wanted to read her origin story. But when I looked her up, I discovered she’d only told the narratives of others. So, I decided to create a space just for her, and make it a coming-of-age story. That term is often used towards kids and young adults, but the desires of the human heart don’t go away with age, they just move with whom the person becomes.

Given the traditional stance and structure of fairytale, I became interested in juxtaposing that with modern society. Place and the contrast of beautiful/ugly have always fascinated me, so it came naturally make a haven where an older woman could experience romantic love and motherhood for the first time, while also tethering her sense of self to nature and animal life. The ugly came from the world’s cruel treatment of her and the environment. The land and woman are beings whose resources are taken until only toxic, painful remains are left behind. The cold, invasion of houses that will never be homes and people who can only be bought, sold, or otherwise consumed was a natural next step in a increasingly unnatural world. The heartbreaks that women go through with love affairs, empty nests, and self-discovery mirrored the struggle of Mother Earth. Those all presented phases of isolation where MG’s world continued shifting underneath her feet.

Amid uncontrollable changes made to family and environment, the old woman is the one constant. Given the losses she goes through, a happy ending was earned, necessary. A place of elevation, mobility, where she takes her life into her own hands, communes with nature on a plane that society can’t interrupt. In another version of the story, I might have shown how the current framework of society leads to its destruction, but in the current version, society is the outsider, one for whom many stories have already been told. Therefore, Mother Goose and her lineage are the horizon where life continues.

What should the reader take away from the connection between the experiences of the three generations of women?

Each generation was a way for the story to continue, for collected stories to be handed down, to carry some of the traditional essence of Mother Goose into a wider community. In that way her stor(ies) act as a network, a legacy that allows her to speak and be heard in a way that her earlier experiences didn’t. Each generation receives the lessons of the matriarch at a younger age, in hopes that they’ll avoid making her mistakes. But each woman must take their own journey to find love and purpose, and while there are differences there are also parallels in their desires. There’s power in the tribes that women sustain for one another. Each provides support in her own way, be it raising one another, keeping each other alive and connected through shared narrative, or keeping a space for each to be found when another is lost.

Can you name a fairytale that conflicts with the themes present in your story? If yes, how does it contrast to your ideas?

A lot of fairytales showcase either a woman’s youth and beauty, a child’s purity or misbehavior, or an old senile woman who takes comfort in evildoings. Fairytales often include romantic love and upward mobility for one of the characters to escape poverty and abuse. And one action or singular pattern of behavior defines each character as good or evil.

A story that stands out from a collection of Turkish fairytales arranged by Ignacz Kumos and Nisbet R Bain is “The Rose-Beauty.” One of the king’s daughters is forced to marry a poor laborer. The daughter is later visited by peris (winged spirits) who bless her future child with otherworldly beauty, which includes pearls for tears, greenery forming with her steps, and roses blooming when she smiles. The king requests the maiden to be married to his son. But a palace dame whose daughter was supposed to marry the prince won’t hear of it. Long story short, the dame eventually tricks the beautiful maiden into giving up her eyes for water so she’ll no longer be beautiful.

Lots to unpack here. Aside from the presumably incestuous arrangement, is women competing for men’s affections at the cost of their own soul. The desperation to be the most beautiful and have access to a life of security is strong. An older woman tears down a younger in order to succeed. In “Mother Goose,” the women aren’t competing for resources or attention. Their actions aren’t motivated by the male gaze. Beauty isn’t defined in a way that excludes each other. Pain and rejection don’t devolve into a taste for innocent blood. While the choices of each character plays a role in their lives, their mistakes don’t define who they are as a whole. They are flawed, but find redemption in each other, nature, and storytelling. Isolation doesn’t translate to becoming sinister or the madwoman thought to be a witch. In fact, part of the magic of Mother Goose and her descendants is educating children through tales instead of violence.

Read Jeneé Skinner’s “Mother Goose,” a Pleiades Online Exclusive, here.

Osasere Ewansiha is a graduate student in the University of Houston-Clear Lake literature program. In her spare time, she enjoys reading, writing, and watching anime or her favorite show, Running Man. Her goal in life is to reach a wider audience with her writing while inspiring a love for reading in others.

Osasere Ewansiha is a graduate student in the University of Houston-Clear Lake literature program. In her spare time, she enjoys reading, writing, and watching anime or her favorite show, Running Man. Her goal in life is to reach a wider audience with her writing while inspiring a love for reading in others.