“I promise the sunrise can still feel sweet”: Reaching for Tenderness and Kayleb Rae Candrilli’s “Water I Won’t Touch””

By K. Iver

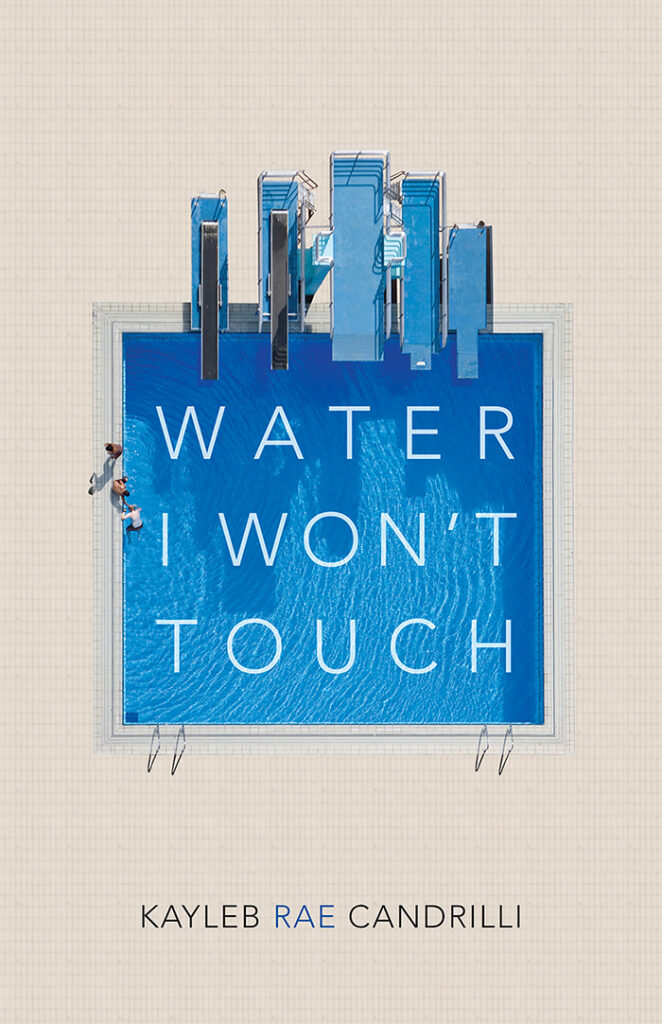

Candrilli, Kayleb, Water I Won’t Touch, Copper Canyon Press, 2021. $16.00.

Whenever I see poetry whose voices reach from a harsh landscape toward tenderness, my scope of possibilities for what’s “allowed” in poems widens. It’s no surprise that power dynamics involving marginalization or familial abuse can, and do, harden their survivors. Kayleb Rae Candrilli’s book Water I Won’t Touch is a stunning example of the opposite. Candrilli’s voice builds a turbulent world from the speaker’s family of origin: a patriarch inflicting violence and addiction onto his children. The speaker experiences the wrong end of a power dynamic both as a child and as a gender-nonconforming adolescent in a rural landscape, both scenarios presenting their own distinct challenges. As an adult, the speaker builds their own world: soft and sometimes peaceful. I trust the authority of this voice: a rural trans person whose parents put them in harm’s way. I’m a nonbinary trans person who came of age in Mississippi, in the 90s, whose parents put me in harm’s way. I didn’t expect to live long. I almost didn’t. My high school love, a trans person, didn’t make it past 26. Long after having lost him to the simple fact of his marginalization, I’m still trying to soften. Part of me wants to stay hard: if I’m not angry at strangers who appear responsible, who will be? Who will protect us? Who will shame the complicit into caring? Softening does not come cheap. Candrilli’s book–through its uses of dynamic imagery and hybrid forms –has charted its own map of possibilities. It begins with genuine curiosity about the body as both carrier and potential healer of trauma.

Candrilli opens Water I Won’t Touch with its own genesis story in “Sand and Silt.” The first line, “In the beginning, there was a boy,” primes a stark contrast from its biblical predecessor with what follows: “who touched me as he shouldn’t have.” The speaker never reveals how old they were then, neither do they make the violation explicit. The word “shouldn’t” carries much of the tone’s weight. This sentence is one of two in a 27-line poem given its own couplet. The other one suggests that the occasion of this poem is a retrospective on a violation, not the violation itself: “I think I knew I was a boy / when the boy touched me.” This information, along with the knowledge that this other boy has grown to be “a violent man,” contribute to the speaker’s gradual clarity on the story. Though the word “beginning” is never repeated, it grows in importance. This is, in fact, the birth of something: “We all have a story like this / innocent in its setting, nefarious / how it stays spurred into our bones / as we grow.” The visceral word choice of “spurred” and “bones” calls attention to explorations of trauma that tend to focus on what has died, what has been taken, what is no longer. Here, Candrilli makes the necessary room for such an exploration while also metaphorizing what lived and what continues to live. The speaker illustrates their body as a desert, “one part longing, / one part need, the rest withstanding.” Difficult an existence it may be, wishing one could “[thirst]” / for nothing,” the voice is one of agency. The poem ends with an impossible dilemma of “violent men” wanting the speaker “to be a violent man” or to be “dead.” The last line, “What a privilege to have an option,” though laced with irony, opens up the possibility that such an option may not fall on either. If there’s one speaker throughout the book, the reader knows they have lived to tell the story, and they do not end up violent.

Though the speaker has known unspeakable childhood violence, though the speaker is well acquainted with the dangers of rural queerness and gender variance, though they can recall these events almost simultaneously with their skill of hunting and butchering animals, they prioritize tenderness over harm with their partner, their sibling, and themself. In another poem, “On the Benefits of Learning by Example,” the speaker recalls, “The first thing I ever learned is that it’s not hard / to kill.” The word “kill” is repeated throughout the book, but never cheaply. In “On the Abuse of Sleep Aids,” the speaker’s mother is so afraid that the speaker’s father will kill her that she drowses herself in Benadryl just to sleep at night. This poem directly precedes one about killing animals when the speaker recalls, with bewilderment, the motivation to hunt: “what does it mean / to carry a dead / animal so close to your heart / in hopes you might / kill some more.” The juxtaposition of human and animal vulnerability does not equate the two. But it does investigate how easily anything with a body one can become accustomed to violence. These lines are powerful examples of how Candrilli explores their subjects by holding questions closer than declarations. The questions build in their precision as the speaker grows from carrying harrowing memories into an adult who makes life-affirming choices. Their poem “Transgender Heroic: All This Ridiculous Flesh” argues that while the speaker’s familiarization with killing runs deep, they also want something to nurture, explicitly so: “soon / I will be gentle enough to mother even / the cherry blossoms. Soon, my body will / mother whoever needs mothering most.” They plant vegetables with their partner. They speak into being their own body’s ability to mother “just about anyone.” They implicitly nurture the reader by promising them that “sunrise can feel sweet.” This idea pushes against tropes of the barely-surviving victim who, at best, is afraid of beginnings and, at worst, meets each day with dread. Who gets access to “sweetness” has socio-economic implications. Candrilli’s promise of access, resting on the word “can,” is not a shaky one. I trust it.

“Transgender Heroic: All This Ridiculous Flesh” adopts the crown of sonnets, each beginning with the final line of its predecessor. Candrilli uses the sonnet, one of the oldest poetic forms, to situate the building of something new. They forsake end rhyme and syllabics, relying on clear and undecorated syntax to highlight their subject. In the crown, each sonnet has their own take on the larger theme. The sonnet has historically been a conductor of tension in sound, imagery, and content. Candrilli keeps this element, packing together instances of harshness such as street harassment with “flamboyant joy” and “soft silence” between the speaker and their partner. This juxtaposition is not unlike the speaker’s drive to safely hold tension of opposites while surpassing their own internalized expectations: “I’m trying to change the future / my blood has written for me.” “Flamboyant joy” would not have such an exhilarating effect without reminders of its opposite or without the persistence of facing and moving through emotional discomfort.

Like the rest of the book, this hero’s journey does not traffic in fantasy-driven hope for its own sake. (The word appears “painfully” and “foolishly.”) Instead, the poem insists on reimagining what vitality in a harsh landscape can look like. Just like one can build, modify, and repurpose one’s body, the voice of this book builds their own world that’s not only habitable but as natural for them as growing “mint” in their “open” “mouth,” or planting “rosemary” in their “open” “belly.” The speaker wonders, “don’t all children with a story of abuse / know something of construction?” The materials left for children who have survived abuse are less than ideal, part of “sweet and sour life,” and the defense mechanisms necessary to survive such a childhood don’t age well. Construction requires creativity, discomfort, use of tools and materials one doesn’t expect, and breaking rules that serve no purpose. Candrilli keeps the rule of repeating the preceding sonnet’s last line as the first, but only as variations. Because the sonnet is almost as old as Western poetry, many poets have metaphorically “broken” it. The unpredictable rules of this crown add to its vitality, not unlike the speaker’s metaphorical lifeboat, “built from scratch.”

One of the most powerful instances of the word “hope” is couched in a painful sonnet imagining the speaker’s “next life” in which trans people live longer lives complete with “castles” that welcome everyone. Vital to the sonnet is the turn, or volta, and when grouped together, Candrilli’s crown presents the fourteenth sonnet as its larger turn. There, the speaker addresses their reader for the first and only time in the book:

“In America, right now, trans people

are impatient to die, because they

are hopeful for their next life.

I hope that breaks your heart.”

The ten-syllable first line of this phrase mirrors the traditional sonnet, but the number of syllables decreases with the next line, sharpening the effect of “I hope that breaks your heart.” Implicit in this hope is the fact that a reader’s reaction can never be certain, but such heartbreak is necessary for collective transformation.The final sonnet continues its acknowledgement of the speaker’s “rage” with an immediate turn in the second line: “But I am still making dinner / tonight, cilantro stock boiled down–/ something small to celebrate.” The section unfolds simple, soft, and safe pleasures laced with the wish that “the whole / world could see the light” that the speaker is generous enough to show them. Candrilli’s skillful positioning of tender, domestic imagery here provides the volta’s release into the final sonnet that gathers each of the crown’s repeating lines. Candrilli again varies their syntax and word choice. When they write the third variation of their promise with the unbroken line, “I promise the next sunrise will feel sweet,” I believe it.

Intentionally or unintentionally, a text responds by default to conversations of its moment, and the conversation centering trans and nonbinary communities is a high stakes one. Candrilli’s book refuses narratives that depict tragic victims for cis consumption. The book doesn’t, however, ignore wounds. In doing so, it acknowledges that “we can hold / just about everything inside of us, whether we want to or not.” This book hopes to break your heart. It also hopes to show you its own: full, tender, and “simple, again.”

K. Iver is a nonbinary trans poet from Mississippi. Their poems have appeared in Boston Review, Gulf Coast, Puerto del Sol, Salt Hill, TriQuarterly, The Adroit, and elsewhere. Their book Short Film Starring My Beloved’s Red Bronco won the 2022 Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry and is forthcoming from Milkweed Editions. Iver is the 2021-2022 Ronald Wallace Fellow for Poetry at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing. They have a Ph.D. in Poetry from Florida State University.

Kayleb Rae Candrilli is a 2019 Whiting Award Winner in poetry and the author of Water I Won’t Touch (Copper Canyon Press, 2021), All the Gay Saints (Saturnalia, 2020), and What Runs Over (YesYes Books, 2017). Candrilli was a 2017 finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in transgender poetry and a 2017 finalist for the American Book Fest’s Best Book Award in LGBTQ Non-Fiction. They have received fellowships from Lambda Literary and are published or forthcoming in Poetry, The American Poetry Review, American Poets, TriQuarterly, Boston Review and many others.