Journals We Love: Editor Spotlight — Rebecca Lindenberg

REBECCA LINDENBERG is the author of Love, an Index (McSweeney’s, 2012) and The Logan Notebooks (Center for Literary Publishing, 2014), winner of the 2015 Utah Book Award. She’s the recipient of an Amy Lowell Traveling Poetry Fellowship, an NEA Literature Grant, a seven-month fellowship from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, and an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award. Her work is forthcoming or appears most recently in The Missouri Review, The Journal, American Poetry Review, Tin House, Tupelo Quarterly, Southern Indiana Review and the Best American Poetry anthology series. She’s a professor of poetry at the University of Cincinnati where she also serves as Poetry Editor for The Cincinnati Review.

Havilah Barnett: Your poetry collection, The Logan Notebooks, won the 2015 Utah Book Award, and more recently, your poems have appeared in Best American Poetry, 2019. Can you discuss your journey as an editor and how that complements your work as a poet? Do you feel that you’ve grown as a writer since you first started editing?

Rebecca Lindenberg: My education in editing started, oddly enough, in book editing. After college at William and Mary, I went to work as an editorial assistant at Henry Holt & Company publishers in New York. I was involved in every step of the process, including acquisitions, editing, copyediting and proofreading, marketing and promotion, and more. I certainly also learned a great deal applicable to working as a poetry editor from the many workshops I both took and taught during my Ph.D. program at the University of Utah and afterwards. But I didn’t really work on a literary journal until I started as the Poetry Editor of The Cincinnati Review. I learned a great deal in my first couple of years in that role, both as an editor and as a writer. It’s very exciting to see what other writers are creating and sending out for publication—I see a wide range of aesthetic styles, formal experimentation, even trends.

Seeing the artistic innovations and commitments of other poets excites and inspires me as a writer to push the envelope of my own writing practice in new and different directions, opens my eyes in a thrilling and humbling way to new perspectives and approaches, and sometimes surprises and delights me in entirely unexpected ways. I have often thought of myself, as a poet, as a storyteller who distrusts narrative, and what I encounter as an editor helps me think through new ways of exploring non-narrative ways of shaping a story or idea. But when it comes to what I choose to publish, I wouldn’t say my own approach to the page determines what I’ll accept. I wear a different hat in that process, if you will. I feel the role of the editor is to curate somewhat regular anthologies of what seems to me to represent the increasingly diverse community of artists that comprises contemporary English-language poetry both within North America and beyond. I suppose the most profound thing my work as a writer and my work as an editor has in common is my desire to make new discoveries, and my willingness to take risks.

HB: When you are the sole editor of a collection, do you ever have moments of doubt in your position? If so, when did you learn to trust yourself as an editor, and what guidance might you give a new editor who’s not yet confident in their abilities?

RL: I may be the sole editor, and it is true that the final say mostly lies with me, but make no mistake – nobody could make an issue like we do at The Cincinnati Review on their own. I rely very heavily on our graduate student editors, whose input and perspective I value tremendously. They’re really, really smart folks. I work closely with them on each issue, meeting regularly to discuss some of my thinking and my choices, and soliciting insight and opinion from them. They are enormously helpful and influential when it comes to vetting work, but most helpful, I think, when there’s work we’re “on the fence” about. I have always been someone who works best when I have interlocutors, someone to help me echo-locate my thoughts. So it’s very important to me that we have conversations at the magazine; it’s almost never just me banging the gavel of literary authority, thank goodness.

I’ll sometimes send something to our managing editor, Lisa Ampleman, and say, “Hey, here’s my take on this but what’s yours?” We often agree, but I think I grow most as an editor when we don’t, and we have to figure out why. And I suspect every editor has doubts—my least favorite aspect of the process is the sending of rejections, because even things we say “no” to often have great merit. They just didn’t happen to make it into that particular issue of this particular magazine. All this being said, I do think at some point you have to trust your gut. But that is something I didn’t only learn to do editing a magazine, and it’s certainly not something I learned to do in solitude. I learned a lot reading admissions applications with colleagues, reading for juried prizes alongside other poets whose judgment I trust, discussing work with friends who are also writers and artists, judging contests, running workshops. I came to see more clearly what I look for in poems, how that is and isn’t different from what others might. And I don’t expect everyone to agree with all of my editorial choices. Universality is not a reasonable expectation for artists or editors. And I don’t expect that the work of learning to trust myself as an editor will ever be done – that seems to me a lifelong and ongoing practice. If nothing else, the world, our art, and our own minds are always changing, and we have a responsibility to keep apace as best we can.

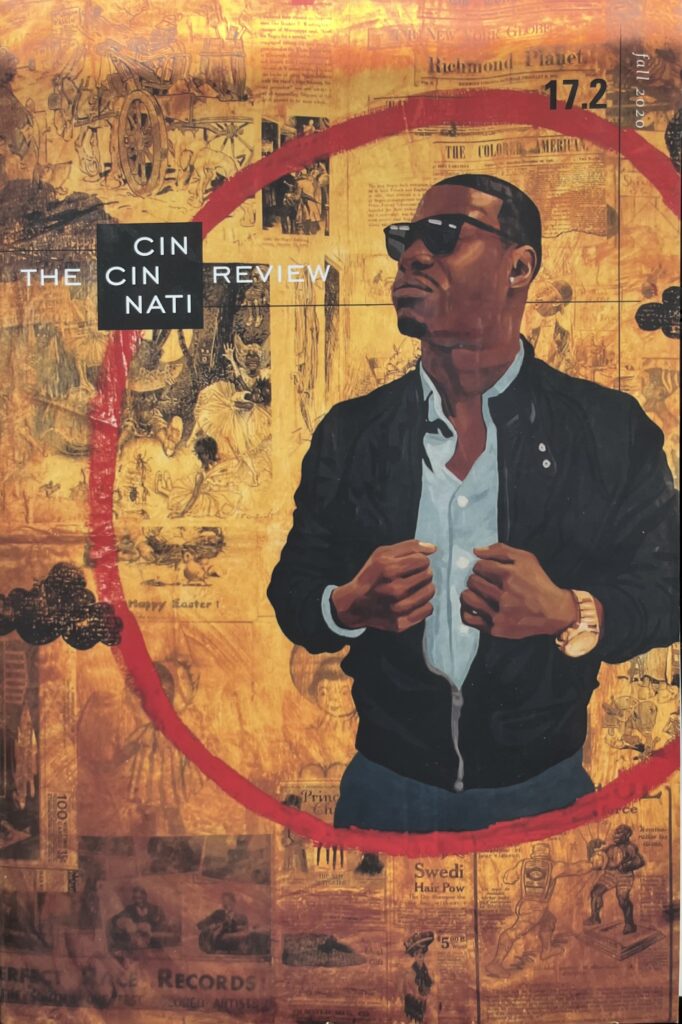

HB: The poetry selection in issue 17.2 of The Cincinnati Review contains a lot of language and imagery about loneliness. Was that intentional? For example, Kaveh Bassiri, in “Repetition Practice,” talks about being “left” many times, and Martha Silano, in “Lunching with Frank O’Hara on My Deck,” describes being alone as “an echo.” Can you talk about the work that you publish, and if corresponding subject matter is important to you? Is there a collective theme you usually look for, or does it vary with each issue?

RL: This is such an astute question, and the answer is yes, there are definitely subtle patterns to each issue. But we’re not in the business of making themed issues. It’s more of an emergent process—I notice that a lot of writers are sending work with similar subject matter, similar ideas, similar imagery or gestures, and without wanting to overdetermine it too much, I take it to mean that’s something in the zeitgeist that’s worth pulling into relief. I can’t say it happens with the same frequency or prominence in every issue, but sometimes it feels simply ridiculous to try to ignore. I would offer that it’s just one of the many ways the submissions themselves (not just my or our curatorial sensibilities) shape the issue.

HB: Is there something specific, in terms of craft, that you particularly enjoy or would like to see more of from the poetry community? And what, if anything, makes you reread a piece or pulls you back to it? Can you describe the weight of that pull?

RL: This is a difficult question to answer. I can say that there are always trends of some kind. For a while there, the word “petrichor” was everywhere. Then there was that season where everything was shaped like a Phillip Levine poem. For a moment, everyone seemed to be writing the contrapuntal. If you’re aware your writing into a kind of trend, you should be aware that if you hope to get published, your version of that has to be really mindfully made to stand out. And if I read seventeen submissions that are all left-justified un-stanza-ed columns and I suddenly come to something fragmentary and spread out all over the page Mallarmé-style, it’s going to inevitably get my attention simply by being different. I can’t say any of that is a deliberate editorial process, just an inevitability.

But I will say, I’m kind of a sucker for affect. Poetry is cerebral, and great poems reward close and considered reading and re-reading, but as I mentioned at one point in my first book, I think of poetry as “how thought feels.” I’m looking for that moment, whether it’s a subtle thrill of surprise or a shiver of recognition or an unexpected swerve or simply a satisfyingly well-rendered and linguistically gripping phrase, that reaches through you, the way great music reaches through you—I want that. I think our readers like it, too.

HB: Has reading submissions led to an increase in your own creativity, or provided you new insights into your own writing? Have you developed a different approach to your writing process?

RL: Haha—it certainly hasn’t made me more prolific. I do a lot, lot more reading these days than I do writing, though I carve out enough time for what I need as an artist most years. I find the process profoundly humbling a lot of the time. It reminds me how many fabulous writers are out there making really important, really impactful work, and as a writer, I am a little one of a large many. It reminds me that I’m part of a community of enormously talented and ambitious folks, and it reminds me that I want to be the kind of artist whose work is always somehow different from her previous or even most recent work.

But it’s also reassuring, in that it reminds me that art is a process and even great artists don’t always get it right the first time out. And that there’s something democratic about the page—it’s blank, for all of us, until we start to try to mark it up in a way that’s meaningful to us. And sometimes we succeed in realizing our vision in ways that others connect with, and sometimes we don’t. I love it so much when artists submit and resubmit and resubmit and I can see their work evolve and change. I love it when someone really new to publishing their work sends something in and they’ve just absolutely nailed it. It reminds me that all artists have ups and downs, and that failure, which I absolutely believe is an essential and necessary part of the artistic process, is part of all of our artistic processes. And I will champion that forever.

Fail, then fail better, right? Artistic gifts can go wasted without a little stick-to-itiveness. It’s hard to be patient with ourselves, especially with a 27-hour social media news cycle that seems to be demoralizing by design. But that’s where the good stuff is hidden—failure, and patience. I think being an editor, on this side of the process, helps remind me (as an artist) to keep the faith.

HAVILAH BARNETT is an undergraduate student at the University of Central Missouri, where she also works as Assistant Poetry Editor and Assistant Blog Editor for Pleiades: Literature in Context, and as Poetry Editor for UCMO’s undergraduate magazine, Arcade. She was awarded the 2022 Ginny McTighe Creative Writing Award and has won Button Poetry’s 2021 Short Form Contest.

This interview was lightly edited for clarity and formatting.