“How They Were Kin”: A Review of LURES by Adam Vines + An Interview with the Author

By Brandi White

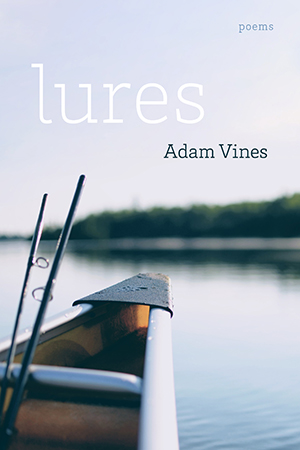

Vines, A. Lures: Poems. Louisiana State University Press. 2022. $17.95.

One of the first things the reader will notice about Adam Vines’s latest collection of poetry, Lures, is the tranquil cover image of a broken-down fishing pole propped up in a canoe. John Sekutowski’s soft, high-definition photo wraps around the book’s jacket; because the image is shot from the viewer’s perspective, it sets the book’s tone, and in this way, Lures “lures” the reader to embark on Vines’s journey through “grief, trauma, southern masculinities, and fatherhood,” as LSU Press puts it, from the navigator’s seat.

The poems in Lures are heart-wrenching—both formally apt and linguistically innovative, rooted deeply in Vines’ southern upbringing. The poems are often composed like an extension of therapeutic refuge, allowing him to navigate stages of trauma, grief, fatherhood, and cultural identity. The sonnet “My Father’s Rod: Fishing the Skinny Moon” atones for the underlying grief and trauma in many of the collection’s poems:

While waiting on the Opelousa bite,

or channel cats would do, our fingertips

plucking our fishing lines below the first

eyes, twitching livers we had hooked and cast

into the river’s craw, my father would

relax, the only time I witnessed this.

By utilizing the rich metaphorical world of fishing, Vines lures the readers through memories, both familial and geographical.

Vines dedicates his poem “River Elegy” to Jake Adam York, another Alabama poet, who wrote elegiac poems on the social history of the Civil Rights Movement. Author of A Murmuration of Starlings, Abide, and Persons Unknown,and the founder of Copper Nickel, York’s life was woefully cut too short.

“River Elegy” reads like a wistful dream, as the speaker imagines spending time with York on a river. The reader envisions a mournful speaker sitting on a riverbank in the poem’s most impactful stanzas:

And I bet I would have learned from you

on that night that will never be

what I had to learn on my own today,

that Holiday and Coltrane flirted through

that number, too, and the song owes its breath

to the 1833 Leonids meteor shower,

the night the stars fell. And I imagine

you would have said what I am thinking now:

that a shower of ’33 happens only once

every couple of lifetimes, and even then it

won’t happen if you ain’t paying attention.

“River Elegy,” almost epistolary in nature, resonates with the reader in the way that one might imagine making new, impossible memories with someone dear who has passed. The speaker might have shown York all the things around his old stomping grounds and the places he was most proud of. In this way, we see the otherworldly connections that can happen between two poets—a nod of appreciation across the vast lake of time.

Lures includes an ardent sense of humor, which strikes a lovely harmony in conjunction with grief and trauma. For example, in “At the Customer’s Request,” a short poem that involves a conversation between a woman and her landscaper, the woman asks the landscaper to murder her lawn and fill it in with dirt. The woman’s husband had spent countless years, time, and money pouring his soul into its manicured, prestigious glory; he has since passed away or is no longer there with his wife. The last two couplets read:

I asked her what she wanted me to do,

And she said, “My husband loved this yard—

kill all of it.

She added, “Dirt will do just fine for me.”

This poem asks the reader to consider the hysterical gap between hurt and revenge. The line break after “My husband loved this yard—” leaves the reader expecting a joke or personal reflection about the husband. However, the reader learns it is an earnest matter, and the woman client is not joking. Through this pivotal twist, the reader wonders what has happened: has the husband wronged his wife, has he died, is she angry over the loss of closure, or bitter with jealousy over the lawn? Either way, the poem demonstrates Vines’s ability to move deftly between the realms of humor and grief, and the reader is left with an intimate, genuine connection to the speaker.

My favorite poem in this book was one I must have read ten times. “Coursing the Joints” leaves me sick with sadness for the speaker. In this haunting poem, the speaker runs trespassers off from his grandfather’s beloved homestead. In retaliation, they return later and burn it to the ground. Vines writes:

…I ran my hands across the joints,

from course to course, my fingers spreading out

and snaking through his hands: the fossils he

left behind, the gift the fire gave back to me.

Because of the senseless act of arson in the poem’s beginning, at first, I felt great anger. Upon reading and rereading, I can see, feel, and hear the sorrow, healing, and important work of forgiveness the speaker finds by the end—a commentary, perhaps, on the grueling but necessary art of revision.

Adam Vines’s Lures, an enlightening collection, contains many sparkling gems, deep insights, and a wide range of emotions and experiences. The book radiates a sense of longing, asking us to slow down, to consider our respective hometowns or places of solace. Though the nature of memory, grief, and parenthood can be complicated, it is at once joyful, mournful, hilarious, and grave. Adam Vines’s sense of his roots radiates beneath the water’s surface and delivers us back home.

AN INTERVIEW WITH ADAM VINES

Brandi White: Congratulations on the publication of your latest book of poetry, Lures, and thanks for taking the time to speak with me. First, can you talk about the process of putting together this book? How long did it take to write it, and when did you have a sense of its scope or its arc? Do you ever write towards a book, or did the collection come together organically?

Adam Vines: Lures is comprised of poems I wrote over twenty-five years or so. I wrote the last poem two weeks before I turned in the final manuscript to the editors at LSU Press. I wrote the first poem in the collection six months before that.

I had a sense that the thickening stack haphazardly stuffed into a folder marked “others” was starting to look like a collection with loose thematic ribbons when I realized that “Lures,” the eventual title poem of the collection and an elegy to my best friend of 40 years who died of brain cancer, could be the wellspring. Many of the poems in the collection are elegiac; however, I also have many poems with my love for my daughter at their foundation, along with poems grounded in my adoration for fishing and excitement and bewilderment with the natural world and my personal struggles with faith. Love and loss, grief and adoration teeter on the same edge in this collection. Bewilderment and faith constitute that edge.

I rarely write toward a book, with the exception of Out of Speech, my collection of ekphrastic poems, but even with that collection, I started out writing suites of poems without a “project” in mind. Lures came together about as organically as it could, I reckon. I needed to grow as a human to write it. Loss and love over 50 years made it possible for me to see the lineage of these poems and how they were kin.

BW: Can you talk about the process of selecting the cover art for this book and how you see it speaking to the collection as a whole? In your previous book, Out of Speech, you wrote many ekphrastic poems–what are the connections between visual art and poetry for you?

AV: I chose the cover art for my first collection of poetry, but I allowed the fine folks at presses design the covers for the rest. The cover of Lures reminds me of my youth, when I would launch my canoe into the Cahaba River and fish alone all day, catching redeye and spotted bass, warmouth and shellcrackers and bluegill on Rooster Tails and Beetle Spins and Mann’s Jelly Worms. The human in the canoe on the cover is outside of the frame. The reader sees a two-piece fishing rod that hasn’t been put together yet and the canoe’s bow, insinuating the human has not cast yet and is paddling their way to their first stop. Beyond the canoe, the reader sees an expanse of water and sky and smudges of green trees along the bank. This scene, for a fisherperson, is the most exciting time. It is the start of the journey, the start of the unknown.

I see poetry and visual art as sisters. The Greeks had their allegorical muses, many of whom were attributed to different genres of poetry like Kalliope (epic poetry), whose daughter was Iamb, Erato (erotic poetry), and Euterpe (lyrical poetry), but none of the muses were assigned to painting. The visual arts, as if almost an afterthought trailing behind seemingly more important ideas or simply folded into “creativity,” fell under the purview of Athena and Hephaestus. Nine muses are certainly not enough. In the late 19th century, Henry Siddons Mowbray, an Egyptian-American artist, was commissioned to create nine lunettes for the entryway to a mansion in New York City. He included six of the foundational muses but added three new ones to the mix; one was the muse of painting. How did it take so long to bring her into the sisterhood?!

A talented poet guides us through the intended narrative, primary argument, and secondary arguments by employing and wrangling with syntax and tonal shifts, delayed verbs and language subordination, rhythmic and phonetic patterns and bursts, and lineation, controlling the viscosity and friction of language. The visual artist guides us through the intended narrative and arguments—oh “intent,” what a fickle, subversive critter (should be its own trickster muse)—through color theory, geometry, focal point, brush stroke, texture, and negative space, among many other tools, both poetry and painting employing image juxtaposition in the same manner. Both arts rely on a deft control of gaits, how the pieces move, how they are in conversation with the audience and manipulate its perceptions, even as both, when successful, are essentially “frozen motion,” which is how Andrew Wyeth described his paintings.

BW: We, as readers, are often reminded of the author/speaker divide–that is, that the author isn’t always writing from personal experiences or circumstances. However, in many poems in Lures, you pay tribute to real people, both public figures and family members. Given the fact these poems seem rooted to you personally, how would you describe the creation process for specific poems, such as River Elegy, written in memory of the late Jake Adam York?

AV: Many of the poems in Lures were initially provoked by personal experiences; however, I always try to write to the fruition of the poem, what the poem desires to be, which places me in a position of unknowing, instead of securing autobiography. Poets should be great liars, making the audience believe whatever they are selling. Strictly adhering to “the truth,” however subjectively wrangled, most often stifles creativity by initially creating too rigid of a premeditated frame to work within. Too many folks are concerned with what subject or idea they are writing about instead of how to write about those subjects or ideas surprisingly and convincingly.

“River Elegy” is the last section of a four-section poem I collaboratively wrote with William Wright. We both admired Jake. I wrote the second and fourth sections, and William wrote the first and third. The sections connect through juxtaposition instead of narrative trajectory, I hope. So “River Elegy” is indebted, somewhat, to the first three sections, which I read over and over before putting down a word, and tries to envision how a camping trip Jake and I had planned to go on a month or so after his death might have gone if he hadn’t passed. The poem is informed fiction, what I hope is the kind of “supreme fiction” or balancing of reality and the imagination that Wallace Stevens investigates in “A High-Toned Old Christian Woman,” “Of Modern Poetry,” and The Necessary Angel, his collection of essays. I imagine an event that will never happen at a place, my land on the Warrior River where my family spawned, that feeds me more than any other place on earth. I broke the section off the collaborative poem and included it in Lures because it contains so many leitmotifs common to other poems in the collection—it makes good company.

BW: This series of poems thematically navigates realism, roots, and truths, which often come alongside difficult subjects like abuse, subjugation, and grief. You deftly blend these more difficult poems with moments of humor, such as the poem “At the Customer’s Request,” which gave way to random laughter for me. Where did the inspiration for this poem come from, and do you think it tells the reader a story left up to their interpretation?

AV: I was a landscaper for twenty years before I tripped into academia, and the woman in the poem is based on a persnickety and hilarious 90-something-year-old customer whose yard I tended. Her name was Mrs. Yelverton, and she had outlived four husbands, but she told me to call her Mrs. Mack because she hated her last husband and Mr. Mack was her favorite of the four. When I would knock on her door after cutting her yard, four or five inches of a shotgun barrel would rise into view through the transom. Then when she heard my voice, she would lower the gun and put it next to the door where it resided at all times. She was a badass. I would chat with Mrs. Mack for 20 minutes or so every two weeks for over five years while she wrote me a check. During the summer months, Birmingham, Alabama, was in the 90s with close to 100% humidity, but her house seemed even hotter with no AC on and her, somehow, wearing a thick sweater and a scarf. When she’d hand me the check, she would give me an extra five-dollar bill and ask me to go “down the road,” which was actually a thirty-minute roundtrip drive, to get her a two-piece dark-meat snack meal from KFC and a pack of sailor-cut Camels from a convenience store. The five bucks didn’t come close to the cost, and I had two helpers in the truck who were on the clock, so I always lost money on her yard, but I couldn’t quit her. I adored and respected her. The poem is an informed fiction, with a person who is real in a scene and situation with dialogue that are imagined—“Imaginary gardens with real toads in them,” as Marianne Moore says.

I hope the poem leans toward a reasonable interpretation. I tried to capture the snarky wit of Mrs. Mack when, in the last couple of lines, the character says to the landscaper, “‘My husband loved this yard— / kill all of it.’ / She added, ‘Dirt will do just fine for me.’”

BW: Which poem in this book was the hardest to write, and why?

AV: “Coursing the Joints” was by far the hardest to write. Around five years ago, I had the wonderful opportunity to spend two weeks at the Rivendell Writers Colony in Sewanee, Tennessee. The colony butts up to Walker Percy’s family’s land, overlooking Lost Cove, where Percy wrote during handfuls of summers. This was my first experience in my life where I had no other responsibilities but to write. I know Sewanee well. I was a scholar at the Writers’ Conference in 2008, and I was on staff at the conference for ten years and now attend as a visiting editor. I know most of the caves, hiking trails, and swimming holes on that mountain. It is the perfect environment for me since I am most productive—I think of most of my seeds for poems—when I am rummaging around in the natural world. My second day at Rivendell, after an anxious day of writing awful-ass lines, I decided to get up early and hike Buggytop, an isolated trail through old growth hardwoods that ends at a deep cave with a stream running through it. I turned on my headlamp and started winding through the cave. At one point, I had to squeeze through a narrow, and I felt the smooth, cold limestone, and I started running my fingers over the contours of the stone, which transported me to my family’s land on the Warrior River in Beat 10 of Walker County, Alabama, which my family settled in the 1830s. This is coal mining land, land that was infamous for moonshiners and gun-runners. These limestone caves and outcroppings in Lost Cove that fueled Percy’s imagination and the rock that became the facades for almost all the houses on the mountain and buildings at the University of the South took my mind to the cabin my grandfather built in the 1930s from shale, sandstone, and limestone he hauled from quarries and spoil piles. He scraped the road for the sand he used in his mortar, which has an unusual pink tint from the Alabama clay that comingles with the sand. When I was in my early twenties, after both my grandfather and my father died within two years of each other and I had inherited the family land, some hunters who were running dogs for deer torched the cabin after I had to persuade them off my land when they refused to be civilized.

I left the cave, went back to my writing desk at Rivendell, and dug through dozens of unsuccessful drafts I had written over 25 years about the torched cabin, trying to find some lines that would open a door into another draft. Nothing stuck. Then I decided to do something I never do. I tore the drafts out of notebooks and tossed them, deleted my old files of failed drafts about the cabin, and relaxed. I thought back to the last time I had been to the property, a couple of months before, and how I had noticed, somehow for the first time, the impressions from my grandfather’s fingers where he had pressed the mortar into the joints between rocks when the trowel wouldn’t suffice. That was my way in to the poem. Then, for the first time, I forgave those men who torched the cabin. I forgave them because of the blessing their vile act uncovered, for the reunion they provided with my grandfather, his fingers the same size as mine. Forgiveness was my way out of the poem. That day I wrote the first draft of what became “Coursing the Joints.” The form of the poem took the shape of interwoven Spenserian and blank-verse stanzas. If I would have come up on those men torching my cabin—they left a six pack of empty beer cans and boiled peanut shells behind where they watched it burn—something bad would have happened. As a boy in the hyper-masculine, blue-collar culture of Alabama I grew up in, I learned, sadly, to be mulish, to ball my fists and dig in, to never forgive. Instead, I found catharsis and grace through writing the poem.

BW: As Editor-in-Chief of Birmingham Poetry Review, you’ve clearly spent a great deal of hard work and dedication cultivating a beautiful publication, which won the 2020 AWP Small Press Publisher Award–congratulations! Can you talk about the balance between writing and editing poetry? How does your work as an editor inform your own craft, and what do you enjoy most about editing?

AV: Editing a poetry journal, along with teaching poetry writing, has positive and negative effects on my writing. A landscaper’s yard is most often the one that needs cutting in the neighborhood because the last thing one wants to do when they come home after cutting grass all day is to cut grass. The same can go for writing. Many times, after a long day of reading manuscripts, tweezering through poems when proofing, and scribbling on student poems, the last thing I want to do is sit down and draft or revise poems. Editing a poetry journal, I am inundated with what poets are writing at that exact moment. I see the trends and movements and chic subjects and approaches and forms for good and bad, which shapes my poetic sensibility.

I enjoy publishing young and unknown poets the most. In fact, it absolutely thrills me, and many of the young poets I published years ago still send to me now that they are rock stars.

BW: On a similar note, editing a journal is both an act of love and an act of collaboration. You’ve also co-written two collections of poetry with Allen Jih. Can you talk about your relationship to collaboration and how you see collaboration as part of the life of a poet?

AV: Allen and I started writing collaborative poems in graduate school nearly twenty years ago. We were both talking one day about how we seemed stuck in writing about the same kinds of things in a similar manner with similar outcomes and wanted to find a way to write from an uncomfortable, unknown place. So we decided to start sending lines back and forth through email. We had two rules: we would send two lines each time, and when one person said, “cooked,” the draft was finished no matter what, and the other person had to start a new draft. Allen is more interested in literal internal landscapes and landscapes of the mind, and I am interested in the exterior world. Allen is fifteen years younger than me and Taiwanese and Buddhist. I was raised in Alabama with impending Calvinist suffering always nipping my lobes and ashes and dust as spice for my swine. In our second collection of poems we added a third rule: the poems must be in iambic trimeter tercets. In the third manuscript the poems are informed by answers and clues from New York Times crossword puzzles. These collaborative exercises changed us both for the better. I learned that working in a constant slippery state was where my imagination worked best. For me, collaboration has been key to my writing, whether it is collaborating with paintings or people or music or the natural world.

BW: As an avid fisherman, how is writing poems like catching fish? How is it not? If this book were a particular fish, which one would it be?

AV: The old platitude is “they call it fishing, not catching, for a reason.” Nearly all of “fishing” time for a serious fisherperson is spent “casting,” not “catching,” which involves probability or mathematical variance, accuracy, and style. A fisherperson is in constant practice of their craft, trying to put in as many accurate casts in places that hold the most fish. They know predation patterns and spawning cycles. When I am fishing a tournament, I want to put in a certain amount of casts over an eight-hour period. Finding the water that holds the most fish while employing accurate casts from the right rod and reel with the right line with the correct lure and technique is the key. One can cast a jig just six inches shy of a stump and might not catch the fish that is sitting there if the fish is not actively feeding. One must be able to skip a wacky worm like skipping a flat rock ten feet under a dock with just a three-inch sliver between the deck and the water’s surface. Ninety percent of fish are in five percent of the water in a lake or stream or river or ocean. Figuring out fish patterns from water clarity and depth, structural variations, like determining if fish are relating to points, creek mouths, weed beds, fallen timber, rock piles, ledges, and overhangs is a constant puzzle.

Fishing is a cerebral sport—one must be a patient observer, a naturalist, and take note of all sensory details around them. A strong fisherperson can smell bream beds even if they can’t see them, notices the slight pipping or “nervous water” from wads of bluebacks or shad, understands that riprap along a bank holds crawdads and mudpuppies and hellgrammites beneath the water even though they can’t see them. All these observations, all this knowledge, lead the fisherman to tie on specific lures to mimic whatever would be the most probable prey in that particular column or stretch of water. They might walk the dog with a Zara Spook, slow-flirt with a dropshot, drag a Carolina-rigged plastic salamander across a point or rip a lipless crankbait below a dam where shad are wadded up or a spinnerbait through stump rows or along a blowdown, among literally hundreds of other techniques and baits for very specific conditions. Furthermore, a fisherperson fishes differently to provoke a feeding or aggression strike. For instance, a largemouth bass, most often an apex predator in a southern United States river or lake, might feed only 3-5 hours a day during the hottest part of the summer, so a fisherperson may try to piss off the bass to provoke an aggression strike with a bait that has an erratic movement, or the fisherperson creates an erratic movement by the way they work the bait, or, in certain circumstances, the fisherperson downsizes the lure or soft plastic and works it slowly, luring the fish to strike an easy prey.

Essentially a fisherperson must have the correct tool and technique for any situation that arises. If I changed the context and created a Mad Lib where I replaced the fishing language in the last two paragraphs with a prosodic and poetic lexicon, that might be my version of an ars poetica. So, yes, fishing and writing poetry are probably the two most challenging and thrilling and frustrating and rewarding things I do in my life.

I adore thinking of my book as a kind of fish. Thank you for allowing me to ruminate on this! I would say a flounder. A flounder has its eyes on both sides of its body and swims upright as a fry, then one seeps through the body to the other side as it grows, and it settles to the bottom on its side with both eyes fixed above. I love the perspective shift of the flounder. No one has witnessed the flounder’s surroundings like it has. I want to know its underwater wisdom. I hope my collection has similar perspective shifts, seeing the same thing from multiple vantages. Besides that, flounder are one of my favorite fish to eat.

Adam Vines is Professor of English and the Director of Creative Writing at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where he edits Birmingham Poetry Review. He has published poems in Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, and Poetry, among other journals. His latest poetry collection is Lures (LSU Press, 2022).

Brandi White graduated from the University of Central Missouri in 2023 with a degree in professional writing and an emphasis in creative writing, where she worked as the creative nonfiction and arts editor for Arcade. Brandi was named the 2023 winner of the Baker/Starzinger Award in Poetry and the 2023 Outstanding Non-Traditional Student Award from UCM’s College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. She lives in Warrensburg, Missouri with her husband, where they own a family farm.