Featured Essay: “Whip Stitch Finish” by Stephanie Sauer

Someday I will learn this language.

Rio, the city, has many mouths. Each one houses gums hot from infection reaching into arteries. Rio, the city, does not resist personification. Rio, the city, will eat you. It will suck you and serenade you and swallow the crackle of your bones whole. Rio, the city, has no regard for survival, only for living at the epidural edge – at the moment blood pushes pores open, releases scent. The air is composed of saline and the once living. At certain circumferences, their weight calcifies into matter. I bump into one on the way to buy groceries and it slices my arm. I hold the cut with my opposing hand and an incision forms from the inside of my skin, letting air in but no blood out. Rio, the city, becomes home not because it, too, is a postcard like California Gold Country, but because it, too, fails to digest its dead.

[August 2012, Rio de Janeiro]

I take the 170 bus to my studio, pass in front of the National Archive. New banners announce that the archives from the dictatorship are now open to the public.

In an article entitled “Trait vs. Fate” in the May 2013 issue of Discovery, Dan Hurley discusses the epigenetic programming research of Moske Szyf and Michael Meaney, saying:

According to the new insights of behavioral epigenetics, traumatic experiences in our past, or in our recent ancestors’ past, leave molecular scars adhering to our DNA…our experiences, and those of our forebears, are never gone, even if they have been forgotten.

2010, Placer County, California: A friend asks, “Where is my purple heart? My father got one in Vietnam, but what about the rest of us who still have to fight the war he brought back home?”

–

[Setembro 2012, Rio de Janeiro]

All this textile, costura, embroidery in the streets and fairs and galleries homes me.

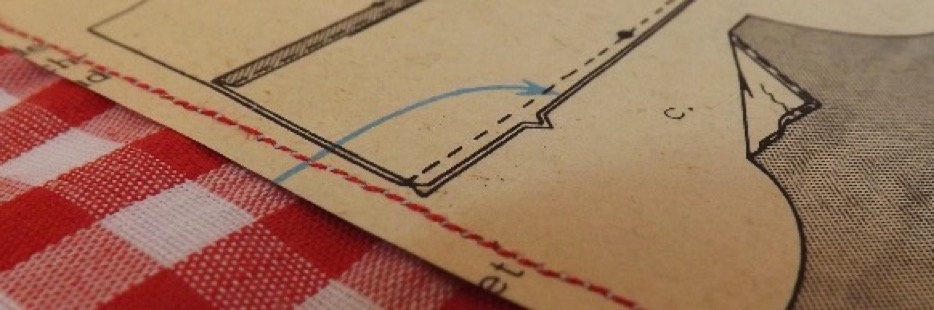

Patchwork onto muslin backing, whip stitch down. Attach back fabric at 2.5” larger (1.5”/side); turn edges in and self-bind.

Making takes form, devours form. I take up stitching. Again. I thread the machine from memory, forget how to thread a bobbin. Remembering takes half an hour. Longing dampens the room, causes dew. I sit down and I write. I write through. I write between stitches. I have to reshape outworn narratives, write into myself new stories. Only then can the making continue.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

2003, Nevada County, California: I know I’m going to die, I just wish I’d get it over with sooner, he told his mother. Or at least that’s what grandma told me. His body had been withering ever since he was three. Ever since we played marbles and he let me win at Clue, Monopoly. The nerves, they said, had no more padding. Thirty years without a doctor’s visit, driving a nine-shift, logging below the summit. Fifty years since the stroke at three. They had said it was encephalitis to cover up the beatings he witnessed. Just huddled his little boy body into a corner and screamed until the paralysis set in. Fifty years and now he slips, bleeds from the skull all over the carpets. When I am not there. When my aunt is out of town. When he doesn’t listen to the recommendations, wants it to end. But he makes it—thirty years of hauling log to sit on a couch by a wood-burning stove in a stick-frame home to wait to die.

–

2014, Nevada County, California: My nephew is born 12:55 on a Sunday to a local sheriff who tells me that the most common calls in our hometown are to report domestic abuse and suicide.

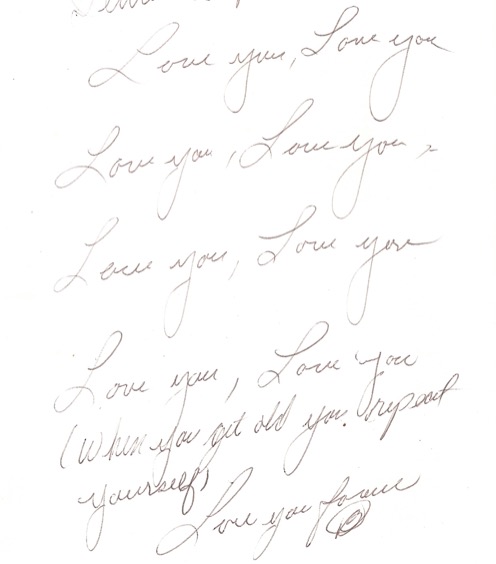

I have not sought release forms to record or publish my grandmother’s stories. They resist the restrictions of copyright law. Her story is part of my story, but it is not my story. The tearing away requires vigilance, a seam ripper, and much stumbling.

2013, Nevada County, California: She has taken to hibernation. Pajamas, curlers, terrycloth slippers. Cups of Earl Grey. The doing and redoing and undoing and losing of taxes. Her children complain that she doesn’t like to go out. They put her on medication. She rebels, then refuses. She worked in a mental ward before and how can her own children betray her like this?

What she will do is go with me to concerts and plays and sit in uncomfortable chairs at storytelling festivals. I take her to see live productions of “The Patsy Cline Story” and “A Street Car Named Desire.” When the scene blackens and the wife is beaten, screams escape from my grandmother’s lungs. Pained, voluminous sighs. People around us shift in their seats, ssshhh her. I ask her if she wants to leave. No. Another whimper, more shifting. My gut enflames. I throw warning glances in the direction of other audience members. Holding my grandmother’s arm, I plan a speech about Post-Traumatic Stress not only plaguing soldiers in case it comes to that, an interruption to this play to defend this feeling woman. I shrink at the thought of disrespecting the artists, but isn’t that part of performance – opening yourself up in real time to experiencing something with others? My grandmother trembles, but still she does not want to leave. I wonder if this is out of politeness or because she needs to see this story end.

–

My grandpa is a legend, I hear at the local diner, taking unnecessary risks with his life and his scrappy equipment to haul log in the Sierras and keep his business afloat.

My grandpa is a legend, I hear.

–

2013: A United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes “Global Study on Homicide” finds that, of all women killed in 2012, nearly half were killed by intimate partners or family members.

2013: A World Health Organization study published under the title, “Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women” found that an average of one in three women around the world “have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence.” Other studies reveal that only 14 percent of women report their experiences of intimate partner violence.

–

“Crazy quilts, born of necessity, were made in an all-over design consisting of pieces of material, regardless of size or color. With the scarcity of materials in the early days of our country, women cut from worn and discarded woolen clothing any parts that were intact or considered useful. They were sewed together in crazy fashion …. In 1870 the lowly crazy pattern was elevated to the parlor by substituting scraps of silks and velvet for the worn woolen pieces.”

-Marguerite Ickis, The Standard Book of Quilt Making and Collecting

–

[December 2015, Nevada City, California]

The “Walking Tour” brochure I picked up in a shop off Broad Street boasts:

NEVADA CITY

Where the Past is Always Present

–

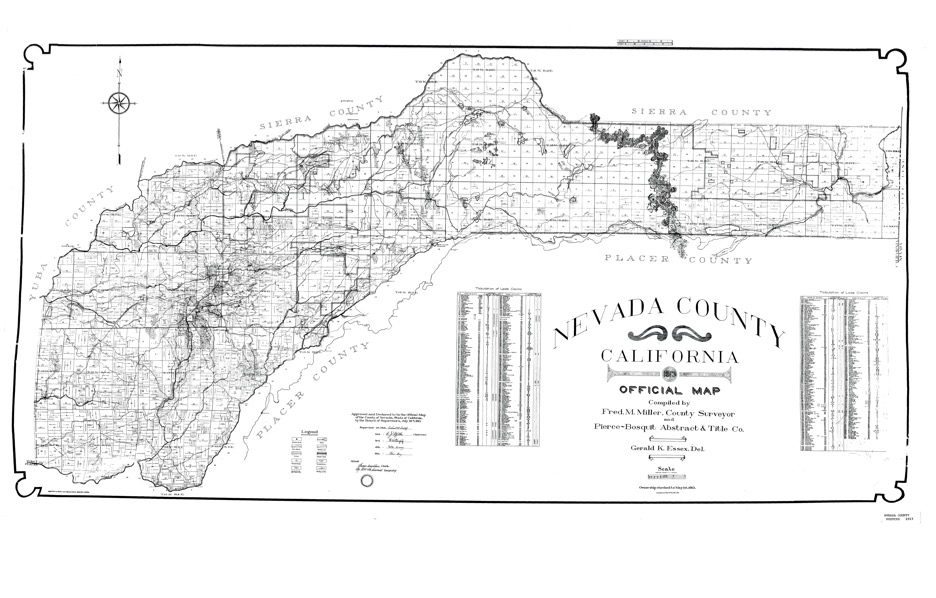

2010, Nevada County, California: If you trace the county lines, ink will outline the shape of a pistol. Teachers at the Catholic middle school find this fact funny. College professors, meanwhile, teach California Gold Country as the site of the most violent chapter in Native American history.

–

2015, Sacramento: Capitol Public Radio announces the first-ever investigation into the links between mining contaminants released into the environment during the 1850s California Gold Rush and the disproportionately high rates of breast cancer among women now residing in the region.

The inner lining

of the cups of the first bra

I bought myself

with the first paycheck

from my first job

with the college degree

that was the first in my family

are stained

from weeping.

My breasts are weeping.

This is not poetry. Weeping is the medical term for the seepage that occurs from a hereditary eczema enflamed by an acute emotional distress, which may or may not also be hereditary.

The weeping does not cause the staining. The broken tissues of my areoles leak a clear fluid. The comfrey root I boil in water, make into a salve, is what leaves traces.

[2014, California]

Tonight I told myself a story of my life that echoed the story of my grandmother. And it’s not even true. Some days I still have trouble untying one story from the other.

Our veins pump five quarts of blood in a full circle throughout our body every sixty seconds. If we breathe deeply, yogis say, we can purify this fluid. I am drawn to this idea that purification is possible by breath. And I wonder, if we don’t breathe deeply. I wonder, is healing just a matter of allowing the blood to cleanse itself in as many circulations as it takes? Am I, at some level, just a body for this blood to pass through, to use to cleanse itself and then discard? Or am I above my blood like my mother tongue assumes?

–

[September 2013, Rio de Janeiro]

I settle on Herança as the Portuguese title of this installation in the upcoming ArtRio show. Inheritance. Not a literal translation, but more exact in this tongue.

–

1992, Nevada County, California: Grandma dresses me in a button-down shirt, pressed with starch, dried by the fireside. She talks me through the binding of a tie, pointed at the end like my father’s, knotted perfect. Don’t you never kiss no man’s foot.

–

When she was first married, my grandmother worked as a nurse in the Department of Mental Hygiene at DeWitt State Hospital. A former Army base, DeWitt housed overflow patients from other California mental hospitals beginning in 1946. By 1960 it housed over 2,800 patients. Grandma was paid an hourly wage to administer medication, bathe patients, scrub hallways. She tells me she had gone to school with several women who were admitted by their husbands when their husbands wanted to remarry. She tells me there was nothing wrong with these women. She tells me she was almost fired for combing a patient’s hair and giving her water. She tells me she was not supposed to touch the crazies.

I am told I cannot trust anything my grandmother says.

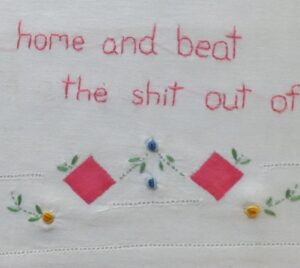

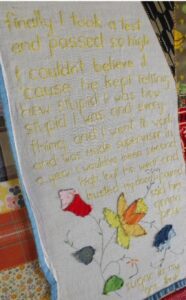

‘Contained crazy’ is the quilting term used to describe a hodge-podge of pieces stitched together into squares that are then stitched into a larger quilt. Containing crazy seems to be the way handicrafts aim to tame, a pre-determined pattern into which we may filter our wild parts, our worries, our questions, our pain. The women I come from stitch theirs, boil theirs, cut theirs, cover theirs with dirt and watch, wait for something else to take shape – a shape that has been chosen ahead of time and is anticipated with care. A choice to repeat the past like a refrain in a hymnal, sometimes inspired, sometimes dutiful. A choice to bring the past into their living by not altering its shape, or by altering it slightly allowing for a particular continuity over time, allowing for safety. You always know your position, the extent to which you are needed inside of a unit, hands full of tradition, fingers calloused. It is family shorthand to call grandma crazy. The screaming, the secrets, the lies, the stitching of sweet things into hidden places all over the house, into her mouth. The cussing at and blaming of grandpa for everything. The out-of-breath retellings of the past over and over and over again. Every sentence in a conversation turning toward a memory. Her never leaving the house. No one can listen to her for more than an hour. The toxicity begins to infect. Some claim she’s made the whole abuse thing up, convinced herself she’s the victim when really it’s the other way around. They blame her for not leaving, say she slept around. Grandpa can’t see why she can’t just let the past go. Some worry about him, call what she does elder abuse. We see him shrinking. We see her growing large. She considers herself strong now, says she don’t take no more shit. The rest of us wish there’d have been a divorce long ago, but it’s too late now. Now, grandma is crazy because calling her this is easier on us. Pinning it on the woman excuses our own complicity in the normalizing of her pain.

Stephanie Sauer is an interdisciplinary artist and the author of Almonds Are Members of the Peach Family (winner of the Noemi Press Book Prize for Prose) and The Accidental Archives of the Royal Chicano Air Force (University of Texas Press). She is a co-founding editor of A Bolha Editora in Brazil and teaches writing in Stetson University’s MFA of the Americas program.