“Delicious Boundary”: Sex and Contradiction in, If the Future Is a Fetish, by Sarah Sgro

by Ellie Black

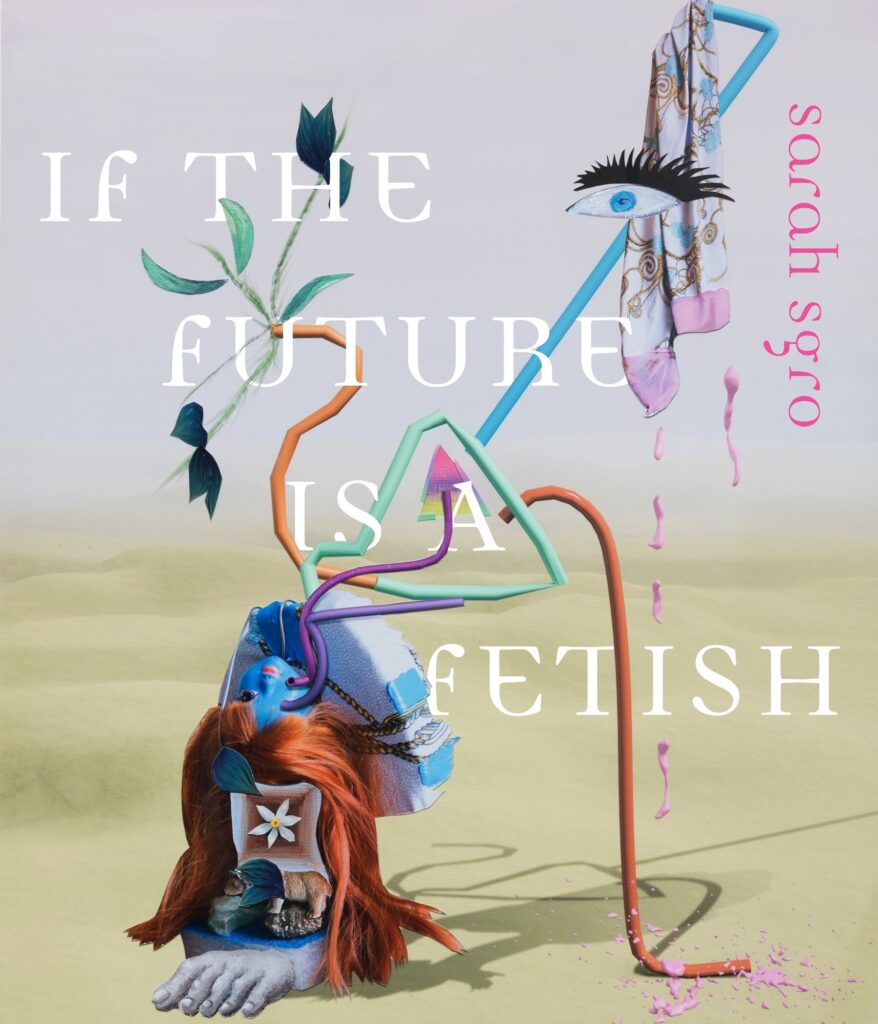

If the Future Is a Fetish, Sarah Sgro. YesYes Books, 2019. 102 pp. $18.00

There’s an indefinable quality to Sarah Sgro’s If the Future Is a Fetish (YesYes Books)—it’s viscerally sexual, sharply academic, and tinged with punk sensibilities, but also greater than the sum of its parts. The collection—Sgro’s full-length debut—contradicts itself almost unceasingly, asking the reader to hold at once (perhaps to gestate) a number of complications: It’s as scientific as it is sensory, as confident as it is desperate, as earnest as it is irreverent, as joyful as it is violent. Its fractured nature espouses, as in the poem “On Your Back Porch I Atone for Every Future Violation,” “incompletion as a fetish.” This collection is holistically queer in its content and its methods, its forms, which is what makes it both so bewitching and so difficult to describe; it swerves and halts, refusing easy definition at every turn.

If the Future Is a Fetish is, in simplest terms, a meditation on queer identity and the possibilities of motherhood therein. The speaker mothers herself, her friends and lovers, and a hypothetical daughter—all to varying degrees of success. The imagined child functions as a simultaneous rejection and fulfillment of heteronormative narratives, a phantom created equally by guilt and compassion, by shame and desire. She simply is and isn’t. Schrödinger’s daughter. “When I hold my daughter in my hands,” says the speaker. “When I menstruate with irregularity & wipe my daughters off my legs.”

The speaker loves the child she has invented—“This poem named her daughter Space ({}) // This daughter lives inside this poem ({})”—but is also wrought with fear (and grotesque curiosity) about the possibility of harming one’s own child, whether intentionally or unintentionally: “I want to have my child and eat her too ({}),” says the speaker. Then, “mmmm my mother // everyday i eat my unborn child // as a light snack.”

Motherhood here is a necessarily sexual space, despite the fact of queer reproduction’s tenuous connection to (hetero)sexual acts. As Sgro writes in the book’s functional foreword, “Apologia: ({}),” “({}) should not conflate maternity with anatomy.” Later, “I dream of solitary procreation. // I dream that I am moss expanding into other moss.” The speaker desires sex without reproduction and reproduction without sex, both contemporary possibilities—indeed, aspirations—for a queer woman. The speaker doesn’t reproduce with her lovers—J, A, M, and X, a chorus present throughout the collection—but instead paradoxically reproduces them, becoming “pregnant with names. J, A, M, X.” Though the speaker usually communicates through the personal “I” (or often “i,” a devalued self), she sometimes identifies herself as “Sarah” and sometimes “S,” in line with the naming scheme of the lovers’ chorus. She splits into multiple versions of the same self, an act of mitosis borne of contradictory desires and the absorption of outside perspectives:

“Sarah is a big whiner. Sarah is a hypersexual. Sarah hears she’s queer and silently agrees. Sarah is a dyke. Sarah is a fake. Sarah needs to dig deeper in her work.”

The daughter, then, both is and isn’t just an extension of the self, trapped in the liminal space between the speaker’s body and the page. The speaker wants a daughter like she wants herself and like she wants to get out of herself.

The vulvic (perhaps womblike) symbol referenced in “Apologia: ({})” is Sgro’s chosen method to “signal fracture, fragmentation, opening”—all central concerns within the collection—and is used simultaneously as a marker between the book’s sections and a surrogate title for certain poems (often, but not always, poems that invoke the symbol throughout). At different points, it acts as a kind of caesura/censor/word-substitute; as punctuation; as a visual component evoking the matters described in its aforementioned apologia; as a reversal of itself (in a poem reckoning with lesbian identity, for instance, the symbol is repeatedly crossed out). Again, as Sgro writes, it “may be pronounced as the mouth around a yellow moon, as Space, the violence of the skin torn.” It is a new word—a not-word—to describe a sensation/experience/concept that may indeed be unique to the collection itself, an ultra-specific representation of femme queerness.

Sgro recognizes the vulgar in the academic and the academic in the vulgar, citing several critical works (such as Marjorie Swann’s “Vegetable Love: Botany and Sexuality in Early Modern England” and Sarah Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology) through footnotes; she blends the playful, the colloquial—a voice at times almost resembling a Valley Girl—with the high lyric. Consider the untitled poem in which Sgro explores phenomenology through wordplay:

“Phenomenology of no one care / Phenomenology of armpit hair / My friends say I look phenomenal / Phenomenology of yes I do / My mother wants to shave me secretly at night but I am a / phenomenon”

This book is deeply sensory, rooted in visual, physical, and aural experiences: the speaker frequently punctuates thoughts and memories with exclamations such as “mmmmmmm,” “nnnnnffff,”and “guhhhhhhh,” even representing audible action with asterisks (“*children sing*”).

If the Future Is a Fetish considers and pushes up against the acceptable boundaries of family, body, and identity; it posits sex, motherhood, and confession as compulsions, solutions to nothing that nevertheless entice. In a sequence of poems addressed to the lovers’ chorus, the speaker says, “congratulations I am queer.” This line is a perfect microcosm of the collection at large: Simultaneously, it evokes birth and revelation, sarcasm and resignation, a flashy wink and handshake cut through with deeper resonance. Just when you think the speaker has laid everything out on the table, she pulls something else from her sleeve—or, rather, from the fruitful void of ({}). Despite it all, everything this book touches is queer, pulsing, alive. Congratulations. We’re here to celebrate.

Ellie Black is an MFA candidate at the University of Mississippi. Her poetry, reviews, and interviews can be found in Best New Poets 2018, DIAGRAM, Booth, The Adroit Journal, and elsewhere. She is an associate editor at Sibling Rivalry Press.

Sarah Sgro is the author of the full-length collection If The Future Is A Fetish (YesYes Books 2019), which won the 2020 IPPY Independent Voice Award. Sgro earned her MFA in Poetry from the University of Mississippi and is pursuing her PhD in English at SUNY Buffalo, where she studies waste, queerness, and the future. Her work appears in BOAAT, Cosmonauts Avenue, The Offing, and other journals.