“Built through our long blood”: Inherited Wisdom and Intersection in Joy Priest’s HORSEPOWER

By Esther Lin

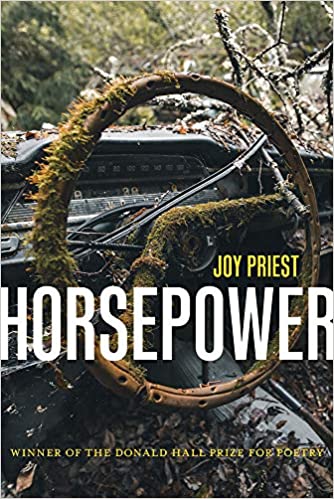

Joy Priest, Horsepower. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020. 80 pgs $17.00

Guns, cars, and racehorses animate Joy Priest’s debut collection, Horsepower (Winner of the 2019 Donald Hall Prize). Set largely in Louisville, Kentucky, the collection is unabashedly regional and pulses with equine imagery. References appear like flashcards throughout, as if to remind the reader this life is a racetrack. It is a life that is fecund, febrile, and deadly. The speaker’s identity is as fluid as the movement of the thoroughbreds: at times she is presented as a Black girl, at times she is figured as a filly on the track, and on occasion she is a reflection on a car’s paint job. With these images, Priest faces off complexities in relation to ancestry, Blackness, the baffling entrance to womanhood—and pushes the imagination on how these identities can cohere, or fail to do so neatly, in a single body.

That racehorses, cars, and guns traditionally belong to male spheres is one of the central tensions—what is the value of a woman, much less a girl, in a landscape that is too often rigidly binary? Most often, the speaker is a receiver of knowledge and inherited wisdom. In a series of poems with titles bearing the phrase: “My Father Teaches Me . . . ,” Priest demonstrates the ways in which the violences of sexism and anti-Black racism intersect within the speaker’s life. For the sake of survival, the speaker sheds female figures, as well as emblems of the female sphere, in order to be close to men. In “My Father Teaches Me How to Slip Away,” the speaker meets her father for the first time, and the poem concludes: “When I step into him & look back at my mother, she / Is on the other side.”

It is the “historical chasm” of racism that parts the white mother and Black daughter, and it is also this family’s tradition that women stand alone and apart from each other. In “My Father Teaches Me How to Handle a Pistol,” the speaker contemplates an ancestress named Elsie—her father’s grandmother—

[H]ow tough she must have been / living alone with two / of the meanest men in our family / of mean men.

The relationship between the speaker and Elsie is iterative; she has replaced Elsie, and now she is the solitary, tough woman who contends with a white racist grandfather and a father who

[K]nows the huge, abstract names / for emotions, when it comes to plants, / but not his own self.

Her grandfather and father are limited in their ways of embracing their complicated descendant. What traditionally belongs to the female sphere—emotions—is lost to the father, and consequently, lost to the speaker.

These lines are representative of Priest’s restraint, wit, and honesty. They live in the quieter poems of Horsepower, while other pieces present a more pyrotechnic poetic, with expressionistic removals of punctuation, the use of all-caps, and the scattering of lines east and west of the page. This formal shift occurs in the poems that portray a speaker out in the world, whose role as the recipient of masculine knowledge has shifted to that of an actor, sometimes in aggressive sexual dynamics.

In “To All the Men that Summer Who Said I Love You,” the capitalized word “It” stands in for the sentiment I love you, whose usage bewilders the speaker: “[M]y fiancé followed me // through Chinatown for an hour yelling It.” Not just the fiancé, but also the father, and also a caretaker’s husband:

& How her husband / had looked at me desperately / as I was escaping & said It: I love you / & How he’d crept into the room / where I slept whispering It: I love you [.]

To hear I love you from a man is dangerous. Love cannot be trusted; it should not even be named. The poem closes without a period: “How there had been no panic // in my body then & then & then & then or then[.]” Such inconclusiveness evokes disturbance and despondency. The speaker is swayed or, at best, challenged at every turn. In a world of men, even an expert like her is rarely permitted to calibrate herself on her own terms.

It is primarily in the language of horses that the speaker is sure of anything, as is declared in the title poem: “I know the horses, / the horses & their restless minds.” Thus the speaker adopts some of these masculine symbols and masters them. What excluded her becomes, by way of a ferocious perception, a source of her power.

Although horses, real and figured, populate the collection, Priest does not romanticize them. Her horses are not mythic, they are not even noble, but remain nearly insensate creatures raised and broken by capitalism. In “Elegy for Kentucky,” Priest describes “the same horse always dying at the curve”:

There she lay toppled like a toy figurine. / Calm but huffing, a laboring machine / making steam.

Hardly glorious and hardly tragic; the loss is so routine that there is no fanfare for her death, except by the speaker’s sober observation: “The lone black filly. / Finished before becoming—[.]” Likewise, the most important earners and losers of the racetrack are not the owners or jockeys or bettors, but the local family, who sell parking spots and lemonade to spectators. As one might expect, the family are entirely barred from the main event. One of the finest poems of the collection is “Derby,” which describes this phenomenon in the form of a triptych. Its tone is coolly unforgiving, particularly of the mother for making a child her “gimmick.” It is with this cool tone that the collection assumes its greatest authority, with the adult speaker who sees clearly, from great distance, and without an obligatory mercy. The third section reads:

[W]e wait / for the races to let out, / for our customers to stumble back / from that fortress / we’ve never been inside.

A sense of cosmic exhaustion and artifice pervade this enterprise: The child speaker smiles because her tight ponytail “pulls” her “face into a grin.” The only horses she is permitted to view are the “[s]pecial occasion barrettes molded / into the white, plastic body of a horse” holding her hair. These are the horses of Horsepower—the ones that make it and the ones that don’t, and all their accompanying substitutes.

Esther Lin was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and lived in the United States as an undocumented immigrant for 21 years. She was a 2020 Writing Fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, 2017–19 Wallace Stegner Fellow, and author of The Ghost Wife (Poetry Society of America 2017). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Gulf Coast, Hyperallergic, the New England Review, Ploughshares, Poetry Northwest and elsewhere. Currently she co-organizes for the Undocupoets, which promotes the work of undocumented poets and raises consciousness about the structural barriers they face in the literary community.

Joy Priest is the author of HORSEPOWER (Pitt Poetry Series, 2020), winner of the Donald Hall Prize for Poetry. She is the recipient of the 2020 Stanley Kunitz Prize and her poems have appeared in the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, APR, The Atlantic, and Poetry Northwest, among others. Her essays have appeared in The Bitter Southerner, Poets & Writers, ESPN, and The Undefeated, and her work has been anthologized in Breakbeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop, The Louisville Anthology, A Measure of Belonging: Writers of Color on the New American South, and Best New Poets 2014, 2016 and 2019. Priest has been a journalist, theater attendant, waitress, and fast-food worker in Kentucky, and has facilitated writing workshops and arbitration programs with adult and juvenile incarcerated women. She is currently a doctoral student in Literature & Creative Writing at the University of Houston.