A Hopeful Ending: An Interview with Rafael Frumkin

By Dean Faucheux

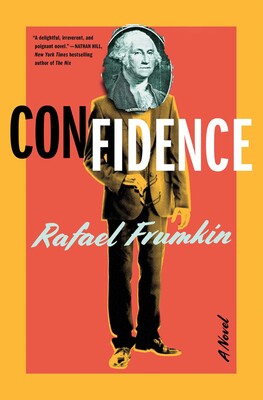

Rafael Frumkin is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the Medill School of Journalism. He is the author of three books: The Comedown (2018), Confidence (2023), and Bugsy (2024). His fiction, creative nonfiction, journalism, and criticism have appeared in Granta, Guernica, The Paris Review, The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading, among others. He is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Southern Illinois University. He and his partner are living the rural queer life with their two cats (Bubba and Cowboy) and one dog (Mina). Find him on IG and Twitter @jeansvaljeans and at his website: www.rfrumkin.com.

Dean Faucheux: Hi and thank you for agreeing to this interview! In the acknowledgments to Confidence, you say that it is a pandemic book. Can you tell me about what that process was like for you? What was it like to write a second book, and in what ways was that different from your first?

Rafael Frumkin: I think the pandemic had some good benefits for me, as much as I would have preferred it never happened. I was privileged enough to experience a stoppage of capitalism. I was working from home and so I had more time to think. And that thinking time became creative time. You know, it segued into contemplation, which segued into creativity to generate new ideas. And it became really fun and less of a nightmare to entertain writing a novel. I knew I wanted something propulsive and I wanted something plotty. Obviously, I care a lot about characterization, but I wanted something that would move quickly. And that was, I think, what made it so different from my first novel, which had in-depth character studies and this very close third-person point of view. Confidence is told in first-person narration and it moves at a steady clip. And I really savored that experience of writing quickly. I wrote and sold the book very quickly, in the span of the pandemic, whereas it took me years and years of writing to finish The Comedown. And it was definitely a good experience. I sincerely hope I have it again. Hopefully not because of a global pandemic, but I do hope I have it again.

DF: It’s interesting that you say the pandemic was a time for contemplation and creativity for you. Many people, me included, had to distract ourselves from the horror of it by taking up hobbies or watching TV or spending too much time on the Internet. How did you manage to write a book that is so anchored in contemporary issues and with Internet culture and at the same time maintain a very focused creative endeavor?

RF: I think for me, it was striking a balance because I have been absorbing scam artistry in the media passively for a number of years, from watching movies like Paper Moon all the way up through Elizabeth Holmes and the Theranos scandal. I acknowledge that I just had quite a lot of privilege, and that I’ve been very lucky. Artists like me were worried of course; we were cautious. Of course, we knew this was a horrible thing to happen. But we could keep ourselves safe to the degree that we were able to think and access those parts of our brain that are typically turned off when we’re performing under capitalism. And it felt weird, because that Protestant work ethic that’s drilled into all of us faded and what returned in its place was this creative renaissance that was like work but didn’t feel like work. That and consuming the other media made it easier to write the book than I think it would have been were it not for COVID.

DF: It’s interesting that you say that, because in some ways, Ezra and Orson, the main characters of Confidence, are both hustlers in a sense—they work all the time. But the more successful they get, the less they actually work. There’re many scenes where Ezra’s just chilling in his office, watching TV while his assistants and his coworkers are doing all the hard work. So obviously, you’ve captured this reality that the more you succeed at capitalism, the richer you get, the less you actually work, even though you project the illusion of working all the time. You wrote the book in a period where you had the time to stop and think and be creative at your own pace, not under the pressures of capitalism, yet you wrote characters who are thriving in that environment.

RF: One of the huge benefits of COVID, and I feel so weird saying that, but it’s true, was this surge in anticapitalist sentiment, which I found incredibly instructive. The system having to grind to a halt for some people, allowed them to actually think about the system and think about the structures we’re operating under and that led to some insights. And so, I was thinking increasingly, this is actually how wealth works, this myth of CEOs working so hard, like owning a company is so hard, being CEO of a startup is so hard—and it’s not at all really. If you look at Ari Newman or someone like Elon Musk, even, these aren’t people who are working. They’re people who are tweeting.

DF: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. My favorite part of the novel is the ending, so I’m going to try to ask a question that doesn’t spoil it for your future readers. A big theme in the story is the power of suggestion, and you manage to explore that theme with both sincerity and irony. The plot revolves around Ezra’s and Orson’s main con, a Silicon Valley exploitation of the new-agey self-care movement that promises to fix people’s psychological and emotional pain with tech gadgets and a pyramid scheme. At the same time, Ezra becomes blinded by the limitations of his relationship with Orson. But in the end it’s not a cynical or nihilistic book–it’s actually a hopeful, even romantic story that departs from your earlier writing. Is that how you also understand this book?

RF: Thank you for that question, because that was a spot-on reading of it. I’m not going to give away the ending either, but I’m just going to say that the ending is hopeful. And you nailed it because the New York Times reviewer didn’t realize this. I don’t know why, but he said that Orson was straight, which is so funny to me. I read a couple of blurbs that suggest that Ezra’s and Orson’s is not a real relationship.

DF: But it’s a love story! The whole book is about their romance.

RF: Exactly! But there are people who say, oh, Orson’s always been using Ezra and he’ll keep using Ezra for XY and Z in perpetuity. And I’m like, you realize Orson loves Ezra, but he can’t let himself love because he’s so used to this chicanery of cheating people out of their livelihoods, he is scared to love. But in the end I think he ultimately does let himself love, but I won’t say anything more about that. I would say that yes, the optimism, the hopefulness, the endurance of love, the fact that love persists, and will continue to exist even after the book ends, the love between those two, I think is where I wanted the hope to be. I’m a huge fan of Succession, I’m sure that much is obvious.

DF: I haven’t watched it.

RF: I think you’d like it, it’s so smart. And it’s very dark, and it’s staunchly anticapitalist. It’s ultimately deeply cynical, and very dark. And I didn’t want that. I didn’t want just cynical satire. I wanted the satire, but I also wanted people to feel like the characters were able to redeem themselves or were able to grow past some of their behavior, although not all of it.

DF: I think that definitely comes through, and it’s much more optimistic and happier than The Comedown, and much more positive than your earlier writing. I was surprised because at the beginning you have to wonder—is Orson being sincere with Ezra? And it becomes quite clear very early that he is, and it’s a refreshing take on the con man story.

RF: Thank you—that’s exactly how I want people to read the book.

DF: That New York Times review also compares Confidence to The Talented Mr. Ripley, which is a great compliment. As a queer-coded text from the 1950s, Highsmith straddles the line between desire and identification between Ripley and Dickie. In Confidence, Ezra’s desire is clear and straightforward, but as a result of the con Ezra and Orson do end up becoming very alike because they embody the same person as ultra-capitalistic Silicon-Valley ‘geniuses.’ How do you relate to that comparison? How do you see Confidence in relation to older queer texts like The Talented Mr. Ripley?

RF: I see Confidence as out there and loud compared to older queer and queer-coded texts. And it also doesn’t intend to be about queerness. My editors say the queerness is incidental to the book. It should be a given that Orson is pansexual.

DF: It is.

RF: Thank you! Other queer folk tend to get it. The ideal reader to a queer text is a queer person. Throughout the midpoint of the 20th century, up until now, we’ve had texts we can identify with whether that queerness has been explicit or subtextual, and that’s why I feel like Confidence is part of a legacy of books like Ripley where we can see the subtext slowly seep into the surface. And of course, there are books from the 50s and 60s where it’s quite obvious, like The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith, but those are farther and fewer in between. So I think that I see Confidence as a flamboyant child of these older queer texts.

DF: I love that. This is a more personal question. In one essay, you talk about writing characters that make you feel less alone. How does that play out with Ezra and Orson?

RF: That essay was written about The Comedown, and when I wrote that book, I was very lonely. I was in relationships that made me feel lonely, with people who were also lonely and did not know how to connect. I was turning to writing and I was writing these characters who would keep me company and who appealed to me because of that loneliness. For Confidence, it was different. It wasn’t so much like I was generating comfort as I was generating friends or companions or people, I can bounce stuff off of, because Orson and Ezra are clever, Orson and Ezra are funny and they’re talented. Confidence was just so much more fun to write. I was already less alone, so I felt even better, and then I became increasingly less alone. It’s just been great to create these characters who are silly, and more than thought experiments, right? More than a question like what if X kind of person found themselves in X kind of situation, what would that look like? It’s more like, well, they’re in it. So let’s just play with it. Let’s watch them figure it out, as opposed to thinking on it.

DF: And how does it feel now that the writing period is over and the book is out in the world and readers can do with it what they will–how has your relationship with the characters changed?

RF: Well, what we’re talking about with Orson is a great example. To me Orson is pansexual, but now that the book is out in the world people will make of him what they will and I have to be okay with that, and I am. Because every interpretation of the book yields some kind of value, some kind of ideas and even lessons about how we live and how we love. Every interpretation is valid, even when it’s not mine. At first I was a little sad that people thought Orson was only manipulating Ezra, but then I realized that the book still works that way. When you write a book, you forfeit control and people can imagine the characters however they want.

DF: I guess that puts the reader on either side of the con, because Orson’s public persona is very different than the private Orson we see through Ezra’s eyes.

RF: Yeah, absolutely.

DF: Why did you decide to create the fictional country of Urman, and what was it like to create Urmanese, which is a great language, by the way. It reads like Esperanto. If you know multiple romance languages, you can totally understand it.

RF: First of all, that’s a very high compliment coming from you, who’s a polyglot. That means a lot to me. Urmanese is based on my knowledge of Spanish, and it’s a mix of that and Portuguese. I have an extensive Spanish background from childhood, even though I didn’t do anything with it for the longest time. It was so fun to invent. I just love languages and I love getting to that advanced level where you can go back and forth, it’s a place where you really get to communicate and it’s so much fun. I created the country as a mix of many countries all at once. US involvement in South America has always been pretty sinister and motivated by capitalism or the hostile conversion of a country to “democracy.” I made up Urman because I didn’t want to have to contend with Bolsonaro or other figures like him. I wanted to be respectful and not pick on an individual country but rather group together political and social phenomena. As a white person not from Central or South America I did not want to tell the story of a place where I don’t belong.

DF: So other people picked up a hobby during a pandemic, and you’re like, let me create a whole new language.

RF: To be fair, I created three sentences of a whole new language.

DF: It feels so much more expansive than that!

RF: Thank you.

DF: On to a nerdier question, just because I like to imagine this. When you’re in the zone, at your utmost level of concretion and focus, what does it look like? How do you make that happen–is it very easy for you, or can you do it anywhere? What’s your desk look like?

RF: I definitely can’t do it anywhere. I have to feel playful. I have to be in the mood and just play around with stuff and not care what’s going on the page. To that effect I have little toys like this strong man or these dinosaurs. I have this frog I got in Cambodia. I want to have that vibe of play, and expressiveness, and that’s how I approach it. For me, the routine unfortunately doesn’t really exist. I’m okay with this about myself. I write in bursts. That’s just how I am. I have a cycle and I like to write really intensely for six months and I’ll produce something on the longer side, like a novel, and then I won’t write for another year and a half. I can’t force myself to write every day, that would break my spirit. It would be horrifying. I’ve tried to write when I’m not inspired, and it’s the most painful experience, I just don’t do it. The Comedown was weirder because it was one project and I was writing and writing and writing. But recently, I’ve fallen more in this cyclical pattern. Sometimes I get really scared towards the end of the cycle that I’m never gonna write again, oh my god. And then I do and I’m like, OK good.

DF: That’s impressive because there is definitely a push toward developing a writerly routine or writing every day or tabling your word count, but you’re not like that. You’re like, I have my own process, and it’s okay.

RF: Yes, absolutely. It’s so okay.

DF: And you’re a really young writer for having produced two novels to critical acclaim and published many essays and short stories in prestigious venues. What would be your advice to younger writers? What would be your deathbed advice?

RF: Oh, my God, you had to make it morbid.

DF: (laughs) Yeah, sorry.

RF: I would tell younger writers not to judge themselves really at all. There are so many younger writers who are like, you’re the first person I’ve shared this with for a homework assignment and I know this is bad. I know this is bad. And I’m like, you’re engaging in a creative task, and that alone is good. You don’t have to immediately produce perfect polished prose. Your desk is a judgment-free zone and you just have to exist. And my deathbed advice to writers is something of a cliche, it’s keep it simple, sweetie.

DF: Sweetie, wow.

RF: Yeah. That’s what my therapist says, and I think I like it better than ‘sister’. Don’t overthink what you’re writing. Don’t overthink, because I’ve been guilty of this too. I get really hung up on epigraphs and I’m like, oh, my epigraphs are too obvious. I need to choose a more obscure writer. It’s such a silly thing to be upset about, it’s ridiculous. There’s so much about the literary world that’s performative. Just ignore all of that if you can, and just keep it simple, and focus on the work, don’t overthink the work either. The work will be what it wants to be, ultimately. Let yourself exist, stop contorting yourself into this pretzel shape for the benefit of capitalism.

DF: In some of your early essays you talk a lot about envy, and especially for writers. You discuss how difficult it is for artists in general to resist the temptation to compare themselves to more successful people, and how difficult it is to be satisfied no matter how successful you are, but it sounds like you now have a completely different approach to it now. What changed your perspective?

RF: As my partner would say, I got out of my own way. I stepped aside and let myself be myself. I thought I had to be like other people. I went to grad school with some people who really blew up. I didn’t begrudge them their success, but I wanted it so much. I was thinking in these zero-sum game terms like they have so much that no one will look at me, and then I realized that was absurd around the time that I came out as trans. I realized that I’m not like anyone, I’m moving in the direction of this specific identity that is typically marginalized, and that is going to give me some opportunity to think differently, to think in ways that are more supportive of the community and less supportive of myself. Eventually I was able to apply the lessons of inclusive queer communities to the literary world. The literary world is an intense and scary place, and it can feel really competitive to people. I choose not to take it seriously and that was my journey to get to where I am, even though I still have plenty of moments where I’m like (screams) back to how I used to be, you know, but that is my official attitude is one of mutual support, and compassion for yourself and compassion for others.

Dean Faucheux is a writer based in Houston, Texas. They are currently at work on a horror novel.