A Breathing Archive of Loss: Claire Meuschke’s, UPEND

by Aria Aber

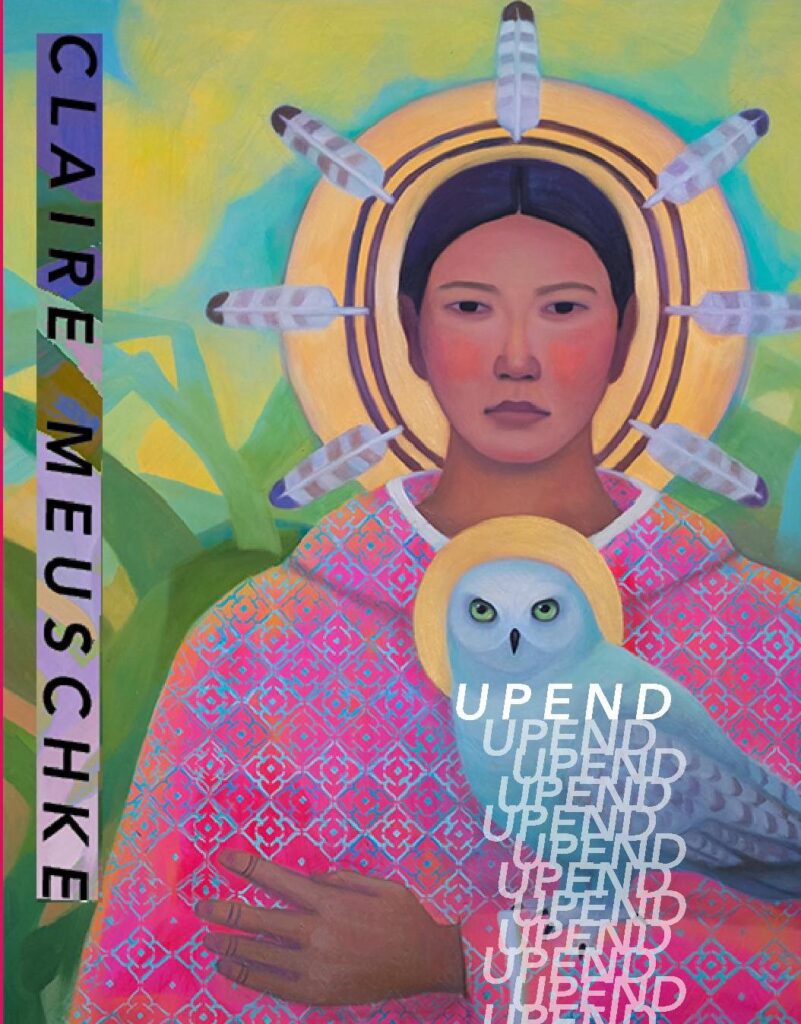

Claire Meuschke, UPEND. Noemi Press, 2020. 111 pages $18.00

In her book The Shock of Arrival: Reflections on a Postcolonial Experience, poet Meena Alexander writes of decolonial literature that it “makes up a shelter, allows space to what would otherwise be hidden, crossed out, mutilated. Sometimes writing can work toward a reparation […] Yet it feeds off ruptures, tears in what might otherwise seem a seamless, oppressive fabric.” Operating within a decolonial and documentary framework, Claire Meuschke’s smart and inventive debut Upend “makes up shelter” and “feeds off rupture” while opposing the “oppressive fabric” of empire––the poems examine and study violence, but also re-arrange and re-envision a place for the violated by bursting the bureaucratic and national seams which are meant to keep human beings separate. This genre-binding collection, which includes documents, photographs, pictures, and a lyric essay, constitutes a breathing archive of loss, tracing what has been lost and is being lost in perpetuation: land, language, and kin.

What is lost, then, is a certain ancestry: at the heart of the book are the immigration documents of Hong On, Meuschke’s grandfather, an Alaska Native and Chinese man whose reentry into the US was processed as part of the Angel Island trials in 1912. Hong On, who was born in San Francisco, moved to China as a child and returned to the country of his birth at the age of seventeen. His interrogation with US officials and other court records related to Hong On’s detention are provided at the beginning of the book for the reader to read through; here, we learn that Hong On was orphaned, and that he was born to an Alaska Native mother. “What was the name of your mother?,” asks the interrogator and he replies: “She was an Indian.” Immediately, the documents introduce a dimension to the work that surpasses the sanitized lyric, thus establishing the author’s sensibility as a documentarian. But the immigration documents also provide the skeleton out of which, through methods of erasure, repetition, and visual deconstruction, a new language is assembled. The author scrutinizes the clinical yet often brutalizing language of government executives by carefully trawling it into the virtuosic territory of her poetic imagination: phrases such as “What was the name of the sister that died?” and “failure to locate the grave of the alleged mother” are repurposed in later poems, reverberating the permanent violence of interrogation and incarceration.

In the vein of other formally inventive writers such as Fred Moten and Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge, Meuschke studies semantics with the curiosity of a metaphysician and the precision of an archaeologist—she is a writer who excavates the root of our colonizing language and discovers its thingness: “I learned English on top of an estimated / fifty buried languages, / I can dig just inches down / and find obsidian and shells / original daily life.” But she presses even further, considering the symbols and images we make with our alphabets. One of the symbols repeated throughout the book is the conspicuous, almost artistic ornament “—oOo––”, which is lifted from one of the interrogation pages and serves as the title for many of the poems. The ambiguous, unexplained symbol—O being both a letter and a number—launches the poet into surrealism, allowing her to defamiliarize the abstruse quality of state violence with poetic exactness: “The — oOo — symbol conjures less loss and less error. Each shape remains intact.” Meuschke also draws attention to further sloppy and imprecise markings within the court transcripts—often, we find human errors in bureaucratic documents, reminding us of the failures of the abstract laws that define and restrict our concrete lives. Wondering what the symbol could signify, the speaker declares the small Os to be in the distance or children, and identifies the double hyphens as wings or borders. This playful metaphorizing does not only deconstruct poetry in a post-structuralist manner, but, by elevating the mysterious slip “–oOo–” into a meaningful anthropomorphism, it resists the dehumanizing carelessness inherent in the Angel Island detentions.

Over and over again, the poet draws attention to what is afforded the privilege to be accurately named within the hegemonic structure of an empire. Colors, for example, are named in abundance. The “paint company Sherwin-Williams has over forty names / to describe any shade—brown to yellow to grey—as gold / their logo reads ‘cover the earth’,” the speaker says, detailing the absurdity of their colonial company slogan. There are entire pages of paint swatches of different “gold” hues, corresponding to the color palette of the California desert and its brutal history. Formally, the pictures of paint swatches signify the artifice of naming, and of color and paint, which parallels the fabric of poetry, metaphor and image. Again, the poet reminds us that naming is never a neutral act, but in fact often a violent one, if not performed with care and tenderness. The list poem “Census” illustrates the racism inherent in the Sherwin-Williams fan deck, where names like “Resort Tan”, “Chopsticks” and “Colonial Revival Tan” sit next to “Polite White.” Meuschke condenses in this list of found names a type of personal census that can also be read as a witty account of America: what starts with phrases like “Ancestral Gold” gives way to colonial allusions such as “Independent Gold” and “Chivalry Copper,” and is then replaced by an overarching blotch of names for whites like “Moderate White”, “Welcome White,” “Divine White.” Eventually, we land in the terrain of ambiguity, “Chinese Red” and “Well-Bred Brown,” “Less Brown” and “Diverse Beige.” Considering the social connotations of the descriptors that precede the shades, this poem exhibits that even a seemingly innocuous object like a fan deck is entrenched in the fangs of white supremacy.

The poet knows that per state laws, human beings are not granted the decency to be named precisely. In various documents, her great-grandparents are identified as “Indian (Unknown)” and “Chinaman, slain.” At one point, we encounter the enlarged scan of what is presumably part of her great-grandfather’s death certificate: “died (murdered).” Meuschke demonstrates how governmental categorization violates othered citizens by pushing their truths into parentheses, their lives forced even into the margins of grammar. Yet, while the great-grandfather’s heartbreaking murder leads to some sensationalist newspaper clippings and documentation, the life of his wife is lived in the anonymous, unarchived shadows. The erasure of her person, who was by patriarchal and anti-indigenous imperatives not deemed important enough to be named in her son’s birth certificate, is, in part, avenged by the manipulation of court documents and the spiritual reckoning in the poems. The inscrutable ancestor becomes a kin the speaker feels called to: “great-grandmother I am closest to you in / bust towns outnumbered by industry / men where women are known to disappear.” What the work accomplishes is more than a reckoning in support of her ancestors, but it’s important to note that the reckoning anchors the book, which, after all, is dedicated to the great-grandmother, “who the archive elides.” Although much of the book follows the story of the author’s grandfather, this dedication positions the book in an allegiance with matrilineality rather than patrilineality, offering “shelter” by remembering those who came before us, those whose stories were “mutilated” and “crossed out.”

Put simply, Upend does not read like a debut; the work is dexterous and distinct, and continually ruptures the language of empire by recycling its mishaps to gather a new archive which indicts, elegizes, and commemorates. The restrained, unsentimental poems shine with a balance of tenderness and intelligence, guided by a keen self-awareness of the subtle and unsubtle ways the speaker’s own psyche has been impacted—“maybe there’s no place to memorize grief,” she admits. And, in a moment of clear-eyed brilliance in the lyric essay “Mechanical Bull,” she insists on ethical accuracy, forbidding herself the balm of superficial beauty. “I resist my impulse to find the lights pretty,” she says of the refinery lights in El Paso-Juárez, which resemble a star-lit sky. Because this book is so profoundly invested in resisting imperialist repercussions, it also mourns the environmental degradation integral in settler violence: “in the news there’s a quantity to the grief / numbers of deaths // acres of land.” The mourning is achieved without melodrama, as in the poem “the scent of herbs is a plant screaming in flames,” which dramatizes the image of a white snake curled around the speaker’s ankle. Even before the reader can imprint meaning on the snake, the speaker analyzes her choice of image: “the snake could be a metaphor for the patriarchy / easy now / a simmer / or an oil pipeline leaking venom / not the Missouri river.” Whatever force threatens landscape and body always swims within reach, the speaker suspended in a perpetual awareness of its proximity. But the poet instructs us stay rooted in our environment, asserting that “for now the snake is a snake.” “Poetry can repair no loss,” John Berger wrote in The Hour of Poetry, “but it defies the space which separates. And it does this by its continual labor of reassembling what has been scattered.” This book, too, is an act of defiance and radical care, because it reassembles what has been torn apart—on every page, Meuschke mobilizes us to reach beyond the veils of document, metaphor, and image, so that for a moment, we can see the world for what it is, not just what it represents.

Aria Aber is the author of Hard Damage, which won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize and a Whiting Award. Her poems have appeared in the New Republic, New Yorker, POETRY Magazine, Kenyon Review and elsewhere.

Claire Meuschke grew up in the San Francisco Peninsula on what once was Ohlone land. Her debut poetry collection Upend is forthcoming from Noemi Press. She received her MFA from the University of Arizona.