REVIEW OF SAFIYA SINCLAIR’S “HOW TO SAY BABYLON”

By Yvonne Conza

Sinclair, Safiya, How to Say Babylon. Simon & Schuster, October 2023. $28.99

The buzz around Safiya Sinclair’s debut memoir How To Say Babylon demonstrates the importance of words telling more than just a stellar singular story. Her narrative arc addresses larger truths in the intersections among family, country, colonialism, religion and survival. The book’s very existence is an act of survival. It speaks to a young woman’s determination to live life on her own terms and to assert what is on her mind. Sinclair’s harrowing, troubled upbringing in a strict Rastafarian family is not without beauty.

The buzz around Safiya Sinclair’s debut memoir How To Say Babylon demonstrates the importance of words telling more than just a stellar singular story. Her narrative arc addresses larger truths in the intersections among family, country, colonialism, religion and survival. The book’s very existence is an act of survival. It speaks to a young woman’s determination to live life on her own terms and to assert what is on her mind. Sinclair’s harrowing, troubled upbringing in a strict Rastafarian family is not without beauty.

Sinclair’s personal and historical perspective on Rastafarian culture, an oral one existing without a written constitution or book of rules, critically expands the Blackness in the Diaspora canon. Rastas’ embracement of their theological way of thinking, reflected in their use of language (a deliberate way to break free of colonial style standard English), choice of diet (vegetables and no processed foods), clothing (for example women shouldn’t wear short dresses or pants) and more, is often overlooked. They have a healthy, conscious lifestyle where the body is considered a temple.

In a 2020 interview with The Bookseller, Sinclair stated what perhaps can read as a quest to overhaul the Rastafarian inaccuracies, while acknowledging that being raised Rasta gifted and complicated her life. She writes toward the inclusion of Rastafarian livity that strives for a balanced life. But it’s also harmfully ensnared with patriarchal dominance. The devaluation of Rasta females results in their being stripped of identity and freedom—a gender-based violence of servitude.

Rasta culture is one of the things that defines Jamaica in the global imagination, but for a long time, Rastafari were a persecuted minority. So when I was growing up, my sense of being out of place at home was compounded by the fact that my siblings and I were oddities wherever we went: we were the only Rasta children in our schools. It was a strange bubble of alienation.

Her life embodies the various oppressions of racism, male privilege, social exclusions, gender bias, loss and rootlessness, economic hardship and physical and emotional abuse. The book is also a documentation of revolt and rebellion. This disrupter and dismantler, poet and storyteller, fashionista, sister, and daughter takes us inside a world little understood by those outside of it. Sinclair’s clarity about the conflicting cultures and the power dynamics within them deftly breaks apart stereotypes about Rastafarianism and about the Caribbean Island of Jamaica. Jamaica earned its independence from Britain in 1962, yet: “Today, no stretch of beach in Montego Bay belongs to its Black citizens.” One exception: property owned by Sinclair’s great-grandfather.

The aggressions and misconceptions about Sinclair’s Rasta upbringing, pierce with their directness. Her family’s chosen religious way of life spawned ignorance. Schoolmates called her dirty because of her dreadlocked hair. Adults weren’t any better.

My parents had only graduated high school, but they had higher hopes for our future. Academic excellence, they always told us, was a way to escape a run-down life.” She and her siblings excelled at school. “We were all spelling bee champions, we won elocution contests and dance competitions. For my father, our intelligence was a gold token. We were his living proof of Jah’s blessings, proof that Rastafari could outwit Babylon any day of the week. Soon friends and acquaintances wanted to know my mother’s secret. Strangers were less subtle, telling my mother straight to her face that they thought Rastas couldn’t read, so how come we were so bright?

——————————————————————————————

TRUE or FALSE Rastifarian Quiz

- Dreadlocks signify that a person is a Rasta.

- Bob Marley started the Rastafarian movement.

- All Jamaicans are Rastafarian.

- Montego Bay is known as MoBay to the locals.

Answers: False, false, false & true.

Read How To Read Babylon: expect to be educated.

——————————————————————————————

Her mother’s nurturing and education of her children and others instilled a love for language found in nature and books and set in motion Safiya’s pursuit of liberation within a maze of patriarchy. Having an abusive and controlling father—one capable of reaching for a machete to harm you—requires a rebellious heart. Showing love for a mother who has gifted you with a passion for language demands that you write. This book looks to the past in order to see the future and create a bridge of possibilities for the next girl to survive and to celebrate—not be diminished by—the complex gift of womanhood.

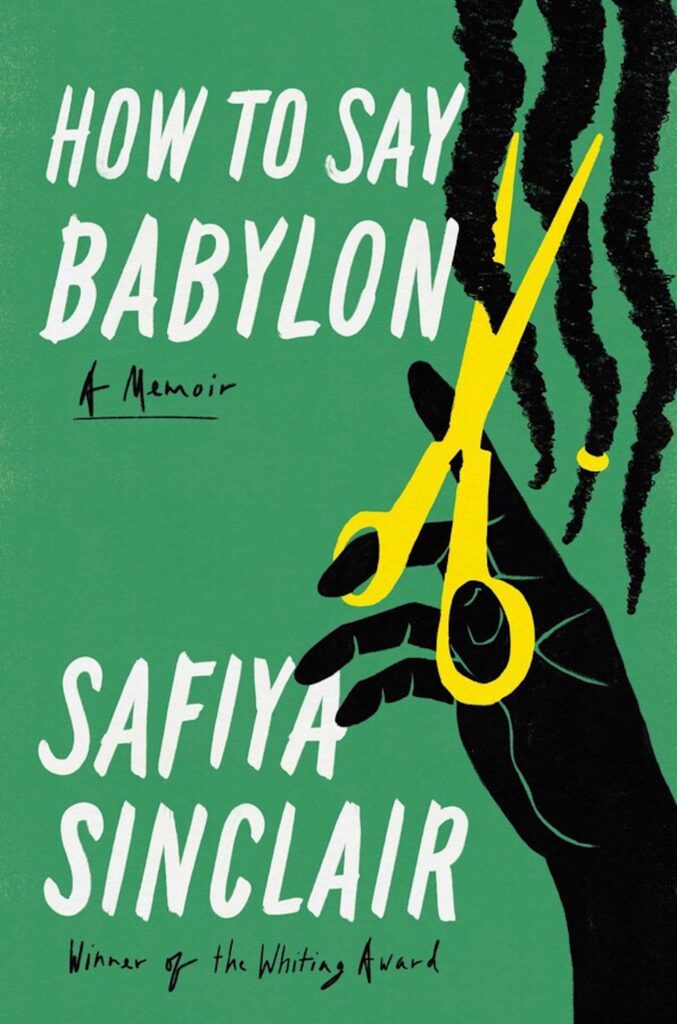

The cover of the book, itself, is an impactful statement. Displaying a held pair of scissors cutting off Rastafarian dreadlocks (hers), a forbidden act, it’s saturated in the gold, green and black contextual tricolors of the Jamaican flag, entwining personal and communal histories. Notably, Jamaica’s flag is one of only two national flags that features no red, white, or blue. Is that linked to Babylon? Bab-uh-luhn, -lon, a former ancient city and kingdom, is the ideological Rastafarian pendulum that swings away from worldliness with its evil and enslavement. “The sinister and violent forces born of western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people, and the corruption of Black minds.”

Sinclair avoids a dull textbook summary of the origins of the Rastafari movement. Instead, she frontloads the book with a vivid “damp April morning in 1966” reenactment of the momentous airport arrival scene of Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia, who Rastafarians believed was a living god. The Kingston’s Palisadoes Airport grounds were packed with an emotional concert of persecuted people who had been outlawed and killed for their beliefs. Unflinchingly too, she also illuminates how at nineteen, stepping into womanhood, confronted by her “strange captivity” within a Rastafarian upbringing, she realized that no movement is immune from developing its own Babylon recriminations.

How To Say Babylon begins with an Emily Dickinson epigraph. “My Life had stood—a Loaded Gun.” Dickinson’s poem structure, a quatrain, consists of a four-line stanza that expresses metaphorical thoughts and emotions, summarized by a woman who is under a man’s control. The gun is not active or passive. It’s triggered. Can one feel safe in that situation? Growing up in Buffalo, not Montego Bay, I knew that complexity. Like Safiya, I had a volatile and talented father who I loved and feared. This book addresses the gutting, unresolvable hurt that exists when the cycle of violence—physical and emotional—is present and where the target best leave before a gun is fired.

Sinclair’s quartet sections echo the four stages of reclaiming a self after leaving an abusive man: counteracting abuse, breaking free, not going back, and moving on. In the first segment, she brings into focus Jamaica and its colonialist past weaved with the historical Rastafarism movement. Next, there’s a focus on her parents—Esther and Howard. At the start, the strong story structure offers room to breathe while incorporating a sentence-by-sentence recounting of oppression without overstating it. She simply homes in on endurance and survival. The dedication and craft that goes into work like this requires unworldly humility, concentration, and the ability to sit with and be in pursuit of reckoning with how the Rastafari culture never embraced her as a woman. And, writing to be heard.

Publicity for this book roared with superlatives. The press release included, “heart-wrenching in its recounting of oppression faced on multiple levels, and commanding in its ultimate note of triumph over staggering odds.” Those comments gave me pause. Surviving trauma isn’t a celebration. I know because I’m alive to tell my own story. Interrogating the past requires unrestricted honesty aligning to a result Sinclair stated in a 2017 Pen America interview. “It can leave you raw.”

I started to read “How To Say Babylon,” and couldn’t stop. Questions formulated in my head. One particular passage in the book articulated what is not often talked about when it comes to writing traumatic material. How would Sinclair respond to my inquiry as follows:

In 2013, Gregory Orr, your advisor at the University of Charlottesville, sent a concerned email regarding your memoir project, citing the importance of revisiting trauma from a place of safety. Adding: “That place of safety—you may not yet have that.” How transformative was that to your work? Do you have advice, or rituals, about navigating the ways of securing a place of safety while revisiting trauma?

My ask is derived from writing about trauma and finding kinship in her words that juggle two jockeying timelines—memory past and living in the present.

I encounter myself again, a young woman in crisis, her head still bent under the terrible blade. Still trying to sever that ghost in her white georgette. Still drowned under fever, her long black reeds of hair. For days I sit with her in the cold silence of Foreign, and each night she reminds me that only I can right this.

Her two previous works of art: Catacombs, a chapbook that combines poetry, memoir and essay, and Cannibal, winner of the Raz/Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry, were keys that likely unlocked necessary and related remembrances for this memoir. This book distinguishes itself from those two when Sinclair places confidence in what Rita Dove, poet and writer, entrusted into her writing arsenal, then shared in The New York Times Style Magazine: “She taught that it’s OK to say a thing plainly; whereas my impulse is to be ornate and lush.”

Reading this book a third time, I wondered about what memoir can do that poetry can’t. Is a poem less interested in telling a story? However, poetry is not abandoned in this work. It’s there and everywhere, stanzas are threaded throughout. “Spring blows like a blousy bitch.”— “His words tore me open, a knife ripping longways through my soft tomorrow.” — “Until the silence itself becomes a kind of freedom.” There’s collaboration between the writer and her unconscious that, for me, felt strongest when Sinclair, who, like her reggae musician father, endures a series of false starts and new hopes. I felt this most in the mentorship she had with Old Poet where, like Sinclair, I once held hope for a person who was credible and able, if they wished, to champion my dreams to reality. A famed educator lured me with his intelligence, connections and false sincerity. The perils within pedagogy should never be tilted to gain a student’s trust in order to take advantage of them.

The Old Poet helps Sinclair to fine tune her craft, learn the canons, and turn her intuition into cellular and skin-like knowledge. It’s intoxicating to have your talents recognized, then be given an opportunity to work with a genius to further develop your craft and, more so, if you had formerly reached a near hopeless state. Safiya earnestly writes about that. Yet again, a transgression, a violence where a mind is confused by gifts given by a man, leaves its mark. “But how else to explain this bright accumulation of days to a seventeen-year-old who exchanged words with one of the Caribbean’s greatest minds?” Which follows pages later with, “It was not how I imagined my first kiss would feel, cold and dead with my eyes counting every overgrown hair on his nose, his alien face smothering mine.” When Old Poet tells her that she’ll outgrow Sylvia Plath and find more substance in Dickinson, is that earlier epigraph perhaps made even stronger?

Safiya’s books, particularly this one, hold literary weight that few writers will ever achieve. How To Say Babylon is a gorgeous, subversive addition to the classics. Sinclair is a transcendent writer whose work stands alongside notables such as Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Kiese Laymon’s Heavy, Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped. A team that started first with her mother is behind Sinclair. This decade-in-the-making memoir holds truths with originality. Rightly, the press release declares: “It’s a story of survival, and the sisterhood of reclaiming a self.”

Yvonne Conza is a writer in Miami. She has words in Longreads, The Believer, Catapult, The Rumpus, Joyland Magazine, Michigan Quarterly Review, Blue Mesa Review, and other outlets. She is the Assistant Nonfiction Editor for Pithead Chapel and is the co-author of the user-friendly dog training guide Training for Both Ends of the Leash (Penguin).