REVIEW OF MEGAN FERNANDES’ “I DO EVERYTHING I’M TOLD”

By Madeleine Bazil

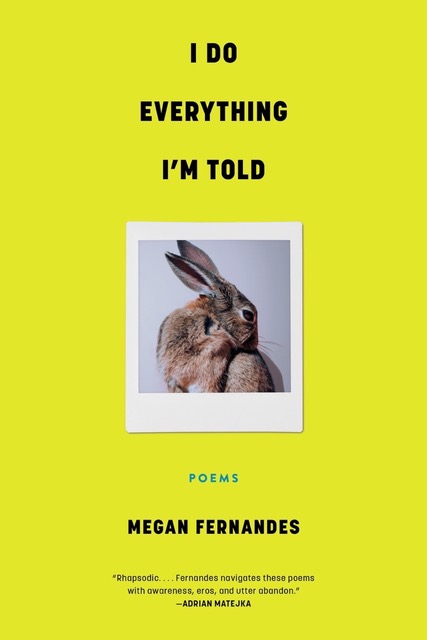

Fernandes, Megan, I Do Everything I’m Told. Tin House, June 2023. $16.95

A poem is a gesture—or perhaps a lurching gasp—toward a felt reality, even an infinitesimal, momentary one. And a sonnet is, most often, a love poem. “Eros is a verb”: so says poet and classicist Anne Carson in the epigraph to the second section of Megan Fernandes’ third collection, I Do Everything I’m Told. To love as a verb; to sonnet as a verb; to verb the world. For all of this collection’s talk of obeisance, I Do Everything I’m Told emerges as a record of active command of memory’s psychic tides. Most of all, it is a book of love poems dedicated to an unwieldy world.

What do Shanghai, Lisbon, Philadelphia, have in common? Cities, yes, but they are also spaces of personal histories—emotional landscapes linked by the shifting terrain of the speaker’s constellations of found and built community. In these poems, Fernandes’ many and wide-ranging locales are not synecdochic objects or sites of desire themselves, but records of motion through and beyond them over time. Throughout the collection, Fernandes appears preoccupied with the relationship between geographic and emotional landscapes, between imagined and real pasts and present. At times these entities seem to move in tandem, a perfect parallel: “My blue wound / plus yours? It could be exquisite in the right / weather, in the right city.” Other times, spatial and temporal relationships are tense, or tenuous. Fernandes derides “a map / that wants to become / something else.” Sometimes a place is just a place; it cannot be traced precisely atop metaphorical ley lines without problematising the very endeavour to do so. “Why do I believe in any land that tells me it is holy?” asks “Phoenix.” Like the poet herself—born in Canada, raised in the United States, to a Goan family by way of Tanzania—these poems are diasporic. The true center of I Do Everything I’m Told’s galaxy is no singular point on the map or place in time. The center is the speaker herself, in all her complexity, traversing it all.

In what is perhaps the collection’s most compelling section, Sonnets of the False Beloveds with One Exception OR Repetition Compulsion, Fernandes toys with the conceit of a sonnet crown: altering her phrasing between poems to negotiate gaps, incongruities, amidst their larger overlaps. Later, the same bank of words is rearranged, removed, pulled apart: “false beloveds” revealed and recast into shapes made starker by erasure. The beloveds may be interchangeable, but the agency—the verbs, the desire—that underpins them remain. Language migrates through opacity into clarity and back again. In Poetics of Relation, Édouard Glissant asks: “But is the nomad not overdetermined by the conditions of his existence? Rather than the enjoyment of freedom, is nomadism not a form of obedience to contingencies that are restrictive?” The city is the false beloved, and Fernandes moves through a litany of them, trying each one on for size even when it is a vexed fit: Freud’s repetition compulsion, indeed. As Glissant posits, these movements are conditional—as is Fernandes’ reception, as a woman and as a person of colour, in different cultural spaces. Even so, her experience of each city is heady and visceral, sensual in the literal sense of the word, governed by touch, taste, and—above all—by communion. As the architect of this narrative corona, Fernandes makes clear that hers is a politics of kinship. This ethos coalesces in the final, deftly actioning line of “Diaspora Sonnet”: “eat, mercy, need, the word, because I fall, too.”

Of course, this is also a collection written in the time of plague. The effect of the tightly coiled pandemic years shows in Fernandes’ devotion to New York City, her chosen home, a metropolis where anonymity and intimacy are interwound particularly tightly—and never more so than during the frightening strangeness of early lockdown. “My walk through this city is a riptide,” she writes in “Autumn in New York, 2020,” a sentiment echoed a few pages later in a description of another mid-pandemic walk through Manhattan in “The First Outing”: “I covered my face, but it was all unessential. It was just longing. To see others, sure, / but also, to stand at the mercy of the monuments that will outlive me.” New York, to Fernandes, is a locus not of beauty, but of community and joy. And joy—raucous, messy, complicated, but affirmed and affirming—is where the book anchors its ending: “We almost crashed a wedding that night / at the Boathouse but lost our nerve,” read the closing lines of “Love Poem,” the collection’s final poem. “We were not / dressed for the caper, but even this felt like rogue joy. / Yes. It was joy, wasn’t it? Even if it was ugly, it was joy.”

As tenacious poems like “Fuckboy Villanelle” demonstrate, Fernandes writes with an inventiveness and sense of play that add dimension to her formal acuity. “In love, the rules are meant to be broken,” reads the opening line of “Los Angeles Sonnet”. Fernandes is irreverently funny—and a poet unafraid to be at odds with herself. Her poems’ world-building layers on itself, sometimes contradictory; always shedding new light. “Contradictions are a sign we are from god. / We fall. / We don’t always get to ask why,” she writes. Desires are named, lovers go unnamed, and reality is a shape-shifting animal as Fernandes articulates a surrealist world inhabited by chance encounters that hold emotional weight, imagined losses that are nonetheless tangible—queering the margins between and amongst rhapsody and grief.

“I cast beloveds. I kill them off, too, / because the muse is mostly a bloodless tool. / A plot device. Don’t take it personally,” reads the opening of “Shanghai Sonnet.” But just a few poems later, a lover, all too willing to relegate themselves into the role of plot device, forces a clarification from Fernandes: an entanglement is “over fast because you knew you were / an experiment. I am your goddamn slum / experiment, you laughed. Your criminal. / No. Just the cruelest person I have loved.” In the tough consonance of this rebuttal, I hear an unwillingness to acquiesce to an easier, less nuanced characterisation of what it means to know and care for someone. I hear a commitment to stickier, more terrifying truths: that love, desire, and connection are vast and complicated notions; that cruelty may be bound up with tenderness not in a performative way but in a vulnerable way; that the exercise of holding another person or community dear is both a body politic and a deeply personal act—a practice of erotics, of suffering, and, perhaps, something more lurking in the intersections or thresholds between the two.

It can be difficult to distinguish, as the titular poem puts it, between “what is kink or worship or both.” The former implies a perversion of the latter—or might it be the other way around? When considered through Fernandes’ expansive yet exacting gaze, the distinction between the two concepts is tangled, maybe even elided. Kink and worship are both states of acting on consuming, immersive love. Love as put into practice, with parameters and structure and ritual; love as a verb.

Madeleine Bazil is a multidisciplinary artist and writer interested in memory, intimacy, and the ways we navigate worlds—real and imagined. Her poetry and criticism is published / forthcoming in Seventh Wave Magazine, Stanzas Poetry Magazine, Sonora Review, One Hand Clapping, Dreich Magazine, Split Lip Magazine, and elsewhere. She was long listed for Palette Poetry’s 2023 Rising Poet Prize.