“Speaking the Language of Wounds:” a Review of Lee Ann Roripaugh’s, Tsunami vs. the Fukushima 50

By Julia Bouwsma

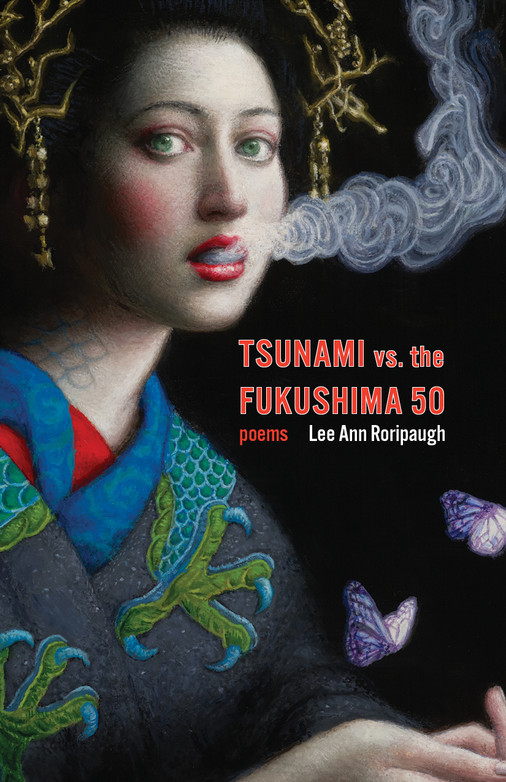

Roripaugh, Lee Ann, Tsunami vs. the Fukushima 50. Milkweed Editions, March 2019, 110 pages. $16.00

“The disaster… is what escapes the very possibility of experience—it is the limit of writing. This must be repeated: the disaster de-scribes,” Maurice Blanchot wrote in his 1980 L’Ecriture du désastre (The Writing of the Disaster). And this challenge of de-scription—the impossibility of writing an experience so terrible it defies the written word—deeply informs Lee Ann Roripaugh’s fifth collection of poems, Tsunami vs. the Fukushima 50, which takes as its subject the devastating tsunami that struck the eastern coast of Japan on March 11, 2011. Triggered by the magnitude 9 undersea Great Tōhoku Earthquake, the tsunami claimed over 15,000 lives, caused level-7 meltdowns at three reactors in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant complex, and displaced roughly a quarter of a million people from their homes.

To write of tsunami is to attempt to speak the unspeakable and thus to arrive always at “the liminal torn-open, turning / words into invisible birds lifting / unruly as catastrophe…”

From the book’s very first poem, “ontology of tsunami,” Roripaugh makes plain the unfeasibility of her task. “Tsunami has no name,” she writes, “she goes by no name…she remains unnamed.” And so, in lieu of a name, she instead begins by offering up to the reader, through a spillage of breathtakingly haunting images, any unsteady moniker that might serve to grasp the calamity at hand: “call her the scalded splash / of tea jarred from / a broken cup’s cracked glaze,” she suggests, “call her the blood-soaked shirt / and cutaway pants / pooled ruby on the floor” or “ginger’s cleansing sting / erasing the soft flesh of fish / from the tongue” or “the meme / infecting your screen.” Her images are at once gentle and violent. They cut into physicality then swerve away, inhabiting and stripping simultaneously—embodying both the pinpoint moment of impact and the echoing, dissociated ripples of destruction that emanate from it. The viewpoint is like that of a handheld camera, the uncomfortable intimacy of a close-up shot sweeping into a chaotic panoramic and back again.

Because a tsunami is by nature both consumer and consumed, the composite of all it has swept up and swallowed, it is inherently a many-voiced, many faced creature, illusive even as one attempts to plumb the depths of its rage. In light of this, Roripaugh’s veering, multiplicitous approach quickly reveals itself as an organic one. Deftly, she weaves between a prismatic series of portraits in which she examines the tsunami from a multitude of angles (“hungry tsunami,” “shapeshifter tsunami,” “beautiful tsunami,” “tsunami as misguided kwannon,” “emo tsunami,” “tsunami in love”) and persona poems that create a roiling swirl of voices, their disparate “I”s cresting and breaking, knocking helplessly against one another in the surge. Under Roripaugh’s tender gaze, we see disaster as narrated by its mutations, abominations, and castaways: the invisible man in “anonymous, invisible man” who speaks “only / on condition of anonymity” then tells us “I decline to reveal / my internal radiation levels” before describing how “I got off the train, slipping / into the city’s stream… / and then I quietly disappeared;” or the child of a TEPCO worker in “white tsubame” whose newly-sprouted white swallow’s wings “grow larger / and more unwieldy, become / difficult for me to hide / underneath my hoody;” or Hisako in “hisako’s testimony (as x-men’s armor),” the orphaned “little blue-haired girl,” who, after being brutally assaulted in an alley, daydreams about her favorite X-men character, Armor, whose “armor’s smelted / from her ancestor’s ghosts // because it’s forged in memory.” The voices Roripaugh calls upon are the voices of the liminal, those at the edge, their identities hybridized by calamity, pushed out of the world until they often seem to cross over, at least partially, into the realm of science fiction or comic book. As with the many faces of the tsunami, their portraits are often displayed through the portrait of another, otherized even through the form of their witness.

Drawing on the tsunami’s natural form as a force that builds and builds without relenting, Roripaugh sometimes engages a causal structure in her poems, trying to lay out the effects of this multiple disaster like dominoes. In “hulk smash,” for example, each stanza begins with “because,” beginning with the ordinary “because it was afternoon / and I was at the carnation farm” and then falling into a catalog of linked horrors that can end only in an impotent act of rage and destruction against “the rusted TEPCO signs reading / Nuclear Power: Bright Future / of Energy”: “because now… / I feel such a huge surge / of adrenaline and rage, / that I have to tear it down.” Because in the end, causality always falls intentionally short in Rorpaugh’s poems. There is no sufficient explanation for these horrors. They defy linearity. Instead there is only the perpetually-caught tidal cycle of doing and undoing, as in “miki endo as flint marko (a.k.a. sandman)” where the speaker tells us: “I keep trying to assemble / my dissembling self / atom by painful split atom.”

This is the nature of tsunami, to be an alchemy of destruction. “She’s the conduit / aperture / cracked / mirror to all that’s scintillant and broken,” writes Roripaugh, “until her compassion mushroom clouds / and swells like a fever / a red infection / a rising tide of salt tears for the world’s fractured core.” Tsunami is the doorway and once one steps through, “what belongs to you / doesn’t.” Through this lens, is tempting to view the tsunami as something even hypothetically merciful—as the culmination of the world’s suffering and violence, but also as a voice for those whose anguish and rage have so long gone unheard (“don’t tell don’t tell / don’t rock the boat / shhhh / shhhh / don’t make any waves”)—to think that calamity might offer a new, clearer view of the human condition and thus potentially serve as a catalyst for change. Roripaugh acknowledges the temptation of this viewpoint, the desire to create a romanticized, healing story out of so much unspeakable pain, asking “how could she possibly stop herself / from the mercy of washing it all clean…?” But ultimately she resists. For as long as healing is still unimaginable, any full transmutation remains unachievable. Tsunami vs. the Fukushima 50 is so powerful specifically because it recognizes that “the ghosts are everywhere” and does not shy from this haunting. Instead, it asks sparely and urgently: “how many centuries will it take… // for this haunted water to evaporate / to be exorcised / and rinsed clean again by light?” And in our current moment of global pandemic, when the spread of the COVID-19 virus in the United States has been likened to a tsunami rather than to separate waves, this is a question that moves beyond the page, out of the water, to sit beside us and wait.

Lee Ann Roripaugh is the author of five collections of poems. Her first collection, Beyond Heart Mountain, was selected by Ishmael Reed as a National Poetry Series winner. Her second, Year of the Snake, was named winner of the Association of Asian American Studies Book Award. Her third collection, On the Cusp of a Dangerous Year, was lauded as “masterful” and a “gorgeous canticle” (Maura Stanton). Her fourth, Dandarians, was described as “a work of beauty and resilience” (Srikanth Reddy). Her fifth collection is tsunami vs. the fukushima 50. Roripaugh has received an Archibald Bush Foundation Artist Fellowship, the Frederick Manfred Award from the Western Literature Association, the Randall Jarrell International Poetry Prize, and an Academy of American Poets prize. She serves as Editor-in-Chief of South Dakota Review and directs the creative writing program at the University of South Dakota, as well as being the state’s Poet Laureate. She resides in Vermillion.

Julia Bouwsma lives off-the-grid in the mountains of western Maine, where she is a poet, farmer, editor, and small-town librarian. She is the author of two poetry collections: Midden (Fordham University Press, 2018) and Work by Bloodlight (Cider Press Review, 2017). Honors she has received include the 2019 and 2018 Maine Literary Awards for Poetry Book, the 2016-17 Poets Out Loud Prize, and the 2015 Cider Press Review Book Award. Her poems and book reviews have appeared in Poetry Daily, Poetry

Northwest, RHINO, River Styx, and other journals. She serves as Library Director for Webster Library in Kingfield, Maine.