Your Life I Have Lived: JinJin Xu’s “There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife”

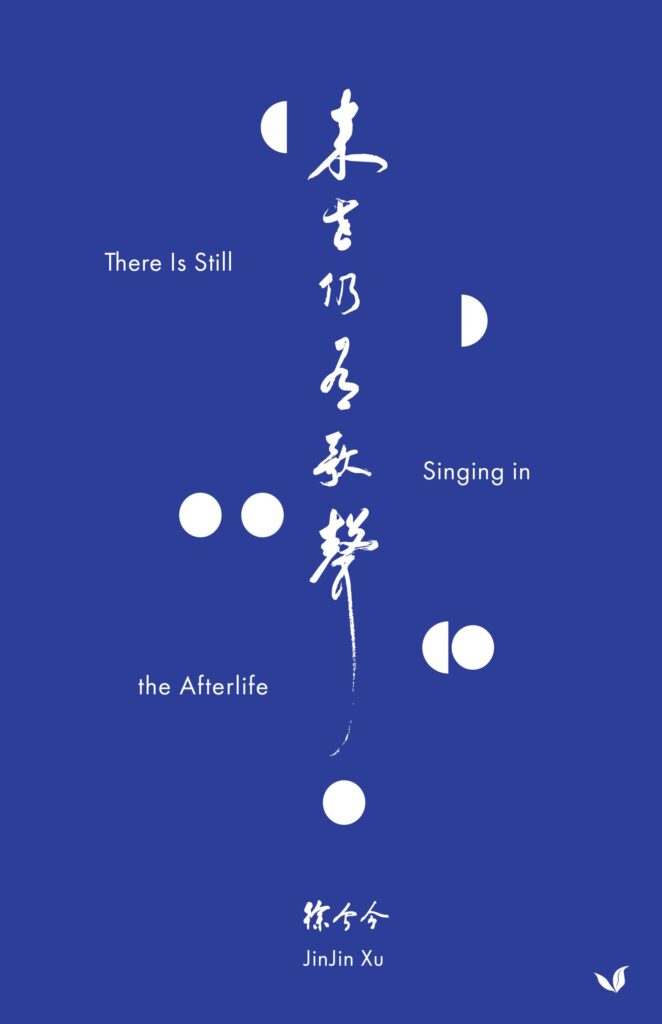

JinJin Xu, There is Still Singing in the Afterlife, Radix Media, 2020, $12.00

Review by Jinhao Xie

Encountering JinJin’s Xu’s poems is like finding a 知音(zhiyin)in a forested park. The rain in Chengdu mists my hair as I find a small canopy to sit under—holding the chapbook so closely as if we were sitting together—conversing about life and the songs thereafter. Soon, I realised that we had been looking for each other half of our lives, and it is no accident that we found each other this way. Every poem in this chapbook is a song. As Xu sings the buried voices of her heart, I, a fortunate listener, find myself getting lost in a familiar world as she (un)veils “the Forbidden.”

Perhaps it is not about what is remembered in history, instead, what is unremembered and unspoken that draws the speaker into listening to the songs from the netherworld. In the opening poem of There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife, “There They Are,” Xu’s speaker paints a family that struggles to survive with a baby born “in the beginning” that “is already too late.” The whole poem is fragmented with images that are both real and surreal: “hunger,” “grasses…aflame,” and a “country road,” for instance. The lives of “the father” and “the mother” are reimagined to reveal and betray the family history that was once told to her. If this poem was a lake reflecting the hard history that has silenced many, Xu’s voice is like a dragonfly rippling its surface. The collective memories of “the great famine,” “the cultural revolution,” and “a nation on the rise,” are often expected of writers with links to China; however, the author refuses such “tradition” by instead, talking about the familial that is closer to each of us: a family trying to survive in an unsettling time, hungry for a life that has yet to begin. Though it might be history to one, it is reality to another.

Her poem, “Night People/ 夜間,” opens with a striking and inventive use of rectangular doorways in different shades of darkness. Visually, it draws a room at night with the door slightly ajar to let in the light, or maybe the gaze of its readers. Later, I realised that I was eavesdropping on a private conversation between a mother and a daughter. An act as simple as switching the light “on” and “off” is filled with the tension of translation: “on” becomes “open” and “off” becomes “close” in English, and to juggle two languages is to choose between accuracy and betrayal. “The daughter” tries to peel back the truth by asking “the mother”: “Do you know somewhere/inside their language lies something/mine.” In the end, the image of the room with an open door becomes a mouth where “in the dark/we finish each other s/bre a t h s/ope /close.” This voice echoes and I sense the poet’s attempt to break free by creating a void in the language where both “open & close” and “on & off” can be of use to create/diminish light.

A sequence of six poems in couplets, “To Red Dust (II),” which won the Poetry Society of America’s George Bogin Memorial Award last year, unsheathes itself like a film. Each poem is a scene, and a vertical curtain of references to 红尘,“Red Dust,” which accompanies each poem linking the present to its past. The opening poem presents us with a benign family trip where both the place and the year are known. A cherished early memory of the poet is seen in reference to the unpolished stone of the Chinese classic, Dream of the Red Chamber. Suddenly, through a thick cloud of red dust, we are brought to the frontline of a protest in Hong Kong, 2019. Then, through a swipe of raindrops, we are listening to a daughter and her father inside a car in Shanghai, 2005, discussing what it means to live amidst these “earthly worries.”

Red dust is a veil that blurs our visions and prevents us from seeing clearly. The following two poems in this sequence show the readers this exact truth, with their place or year redacted in brackets. Being alive is to “hold on,” yet holding on is a privilege of the living. For instance, the daughter’s plea to her father: “Please…do not leave us in the red dust,” reminds us that the dead have no choice but to let go. The poet speaks about the unspeakable: bodies aflame in the past—referencing tragic moments existing in people’s memories but never spoken of, and how without mourning, the dead become nameless and shapeless. In the last poem of the sequence, both place and year are unknown to us as the speaker chants a Buddhist prayer. She could be standing anywhere in time, speaking to the eventuality of our frail lives—in fact, the speaker finishes the sequence with the reminder that, in this life clouded with red dust, perhaps there is “nothing worth dying for.” The bolder resting on the shoulders of the living is ever so heavy. This attempt of witnessing grief is carried out to the maximum at the heart of this pamphlet. Two poems dedicated to her best friend’s brother brought us a new language in experiencing empathy.

“To Her Brother, Who Is Without Name” and “To Your Brother, Who Is Without Name” are at the centre of this red-dusted whirlwind collection. Together, these two poems twin like two worlds separated by a mirror. One world is the living and one world is the thereafter. Many of us are well-versed in mourning loved ones, or those who are close to us. However, how many of us can say that we are truly versed in mourning someone else’s loss? Or are we even allowed to do so in this society filled with the morality police? Xu, while facing self-doubt, is willing to take on this difficult topic.

To be a poet is to create when plain language fails us. JinJin starts this risky quest with:

“I am sifting for a sister alive/slipped by her brother not alive”.

From the generation of the One Child Policy, our dearest friends have become our chosen family members. And to the addressee, “her,” who has been experiencing the loss of a brother, the speaker tries to salvage a body “slipped” by this loss that could resemble a “sister”. Already, the language is ripped apart and thrown into haste. The reader, cannot help but be drawn to Xu’s incredible storytelling ability. She brings me to a mysterious scene in which three generations of women are trying on qi paos in New York City: “My mother readies me/ inching up the zipper to squeeze out/ my woman.” Like her other poems, JinJin enchants the living stories with so much history, alluding to the Opium War and the jazzy nightlife of 30s Shanghai. Yet, her true magic is to make such history mundane so that we are reminded history has never left us. We are still living in it.

“Qi pao” can be seen as exotic to the western imagination and such impression is often internalised by the Chinese to please the white gaze. Not even “my mother”, as the poet points out, can escape such self-exoticisation, declaring “Chinese-air … appealing to whites”. But this is not the point. Despite it all, the qi pao in this poem is not here to please any gaze. Instead, it is a thread that connects two lives separated by history. While both the speaker and the “brother” are considered Chinese, “the brother” accuses the speaker “of being born easy,” because she was born in the country where his family was exiled. While “a city lost by exiles forgets” that “staying was not the same as leaving,” the complications of diaspora means that one will always consider the other, and perhaps the self, as foreign. After all, like the opening poem, Xu’s speakers reminds us that it is all too late. While the living can always choose to go home, the “not alive” cannot go back to that home.

If “To Her Brother, Who Is Without Name” is an attempt from the poet to build a bridge to reach a sister, then “To Your Brother, Who is Without Name” is a letter written to the sister — a chant to reach the brother in the afterlife. Across all cultures, the name of the deceased is often recited in rituals to connect with them in the afterlife. To call upon someone by their name is to wake someone up: they will live “in the land of eternal wake,”,never resting properly. Perhaps, to leave the brother’s name out is the best way to mourn him so that he can finally rest in peace. Unconsciously, as Xu puts it in interviews (https://www.ligeiamagazine.com/winter-2020/jinjin-xu-interview/) on this chapbook, her multidisciplinary practices in film-making, writing, and art, bleed into her poetry. Each line, each line break, is a scene to be savoured. From the start, Xu’s speaker tells us, “It is snowing,” as if the whole world is mourning for the loss of a brother. She tries so hard to make it real, yet she knows this lie will not hold—this memory is “slippery”. But even as memories are slipping away, the act of writing is “a promise” to keep this nameless brother alive somewhere.

It was already the afternoon when I finished the chapbook. A host of sparrows flew across an orange sky as if it was dawn, and I was brought back from a life I never lived. But, why was I not able to rid the feelings etched on my mind— the sharp cuts of grass-blade and the deep trench of not-mine history? Xu’s chapbook is a gift to me. It dares me to imagine the unremembered and to resist (self)censorship. I cannot but help to recommend this collection to many and to anticipate her future body of works.

Jinhao Xie is a Canterbury-based poet born in Chengdu. Their poetry touches on themes of culture, gender identity and the uncomfortable in the everyday. Their poems have been published in Poetry Review, Gutter Magazine, Harana, Spilled Milk Magazine, and Slam! (anthology of spoken words edited by Nikita Gill). They are also active on Instagram and use it as a playground to share some unfinished drafts as they wish to make poetry more accessible to the public.

JinJin Xu is a filmmaker and poet from Shanghai. Her work has appeared in The Common, Black Warrior Review, The Immigrant Artist Biennial, and has been recognized by prizes from the Poetry Society of America, Southern Humanities Review, Tupelo Press, and a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship. She is currently an MFA candidate at NYU, where she is a Lillian Vernon Fellow and teaches hybrid workshops. Her debut chapbook, There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife, won the inaugural Own Voices Chapbook Prize.