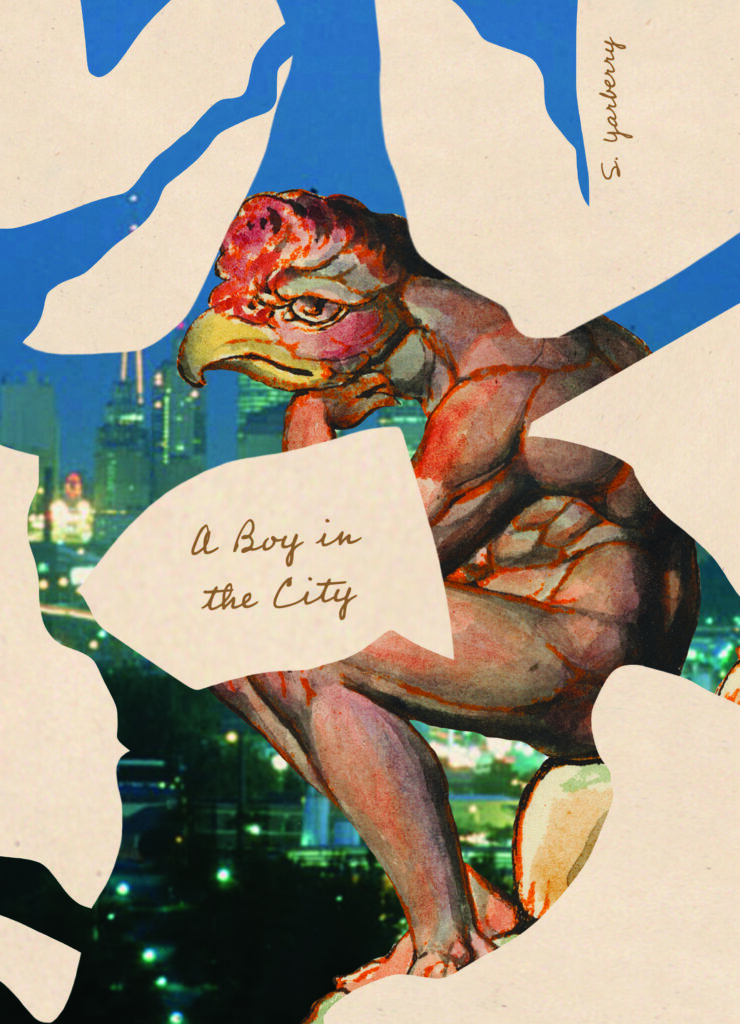

Trans-erotic World-building in S. Yarberry’s A Boy in the City

By Aja St. Germaine

Yarberry, S., A Boy in the City, Deep Vellum, 2022. $16.95.

In the vulnerable poetics of S. Yarberry, I sink easily into a queer futurism where the definition of the erotic has been revolutionized. Yarberry’s speaker carves into the in-between of elusion and seduction, describing their body as “an unknown entity,” and examines the cisheteronormative gaze on queer sex that is desperate for our sexuality to be productive—this same gaze too often decides what makes intimacy meaningful, dictating a hierarchy of intimacies both interpersonally and in the greater living world. Yarberry collaborates with queer theory such as Audre Lorde’s uses of the erotic to redefine relationship-making void of canonical romanticism.

The poetry of Yarberry exists as the antithesis of this hierarchy by intertwining the natural world with interpersonal yearning, often indistinguishable from one another. Yarberry begins the collection by digging into a larger truth of wanting: the desire for fulfillment of needs beyond your individual experience but rather the larger collective of all beings, distinctly pastoral outside of the canonical. Their investment in dismantling the forced dichotomy between success of self and the prosperity of nature is refreshing: the balance between the well-being of both imagines a harmonious ecological future where we consider the health of our external surroundings as imperative to our internal homeostasis:

“Barnacles are dying. How horrible to watch your life

go by and want so much”

(LIPS CRASH WITH LIPS, INEVITABLE, 3).

This compelling weaving of the personal and natural worlds speaks to a larger truth of queerness, that the suffering of the natural living world surrounding us often directly impacts our sense of wellbeing and searching for a harmonious togetherness, too often overlooked by cisheteronormative ideas of yearning.

Yarberry’s yearning is reminiscent of Audre Lorde’s “uses of the erotic:” her reevaluation of eroticism by extending intimacy past the sexual, and instead shifting focus to the communal desire to embody shared vulnerability within queer relationships. This definition of the erotic crafts coalition-building under oppressive interpersonal systems like compulsive cis heteronormativity within our most private relationships. These revolutionary practices of intimacy and desire are what drive queer world-building, and this is expertly crafted into the language of the speaker. Yarberry’s take on the erotic is complex, pairing Lorde’s eroticism with a front-facing sexual desire.

Desire remains prevalent, and Yarberry’s speaker extends their desire in all directions, finding this eroticism in the queerest nooks: our sense of self gets blurred with the city and the wilderness as they pair lovers with barnacles, erotic mouths with purple mountains—the natural is Yarberry, and queer sex is peaches (LIPS CRASH WITH LIPS, INEVITABLE, 3). Their queering of the pastoral revolutionizes the confines of a canonical speaker, pushing the capitalist and colonial boundaries that dictate a typically white masculine pastoral.

A hetero-canonical pastoral, as I would frame it, intertextually refuted by the speaker— “Once, I considered/that pastoral could be/past and oral, not sexually, /of course, but traditionally, /A Past Oral Tradition”—is emphasized and contrasted with Yarberry’s intimate transness in their cityscape-pastoral take (THIS PLACE IS CALLED BEULAH, 74). Their muse, situated within a city setting, invokes a yearning for transcendent eroticism void of romanticism, building the speaker’s voice beyond gendered roles and into a trans self. I am particularly fascinated with the navigation of the speaker through the queer pastoral, intertwined with an unreachable desire for the beautiful within mundane tragedy and it offers solace:

“The dead deer are everywhere—

as I drive home from up north.

Everything flat. The sky

pink as girlhood and purple

like an adult bruise. I’m overcome” (ISLAND OF CALYPSO, 78).

Yarberry’s lines speak volumes about the overwhelming destruction that often defines what it means to coexist with painful reminders of capitalist destruction. Their contrasting imagery is heart-wrenching, gracefully encapsulating a convergence of world-building and world-critiquing. The speaker is unnervingly intimate, making questionable our perception of our surroundings and blurring our personhood with the animals mutually surviving around us. The poem, DIRT, coincides animal life with the speaker’s, contrasting robins with pink robes and glasses of wine, a lover’s hands gently rescuing a beetle. Yarberry preys upon our compulsion to remain separate from creatures, equating the speaker’s most vulnerable private self with that of this delicate beetle, exposing animalistic natures:

“The beetles never flutter–just crawl

unromantically across the soft brown tiles.

Nowhere to go! Nowhere to be! I sing out” (DIRT, 65).

In their gravid poem, “Medusa,” the speaker’s conversational tone is an unarming satirical celebration within the trans body. Yarberry envisions a futurity in what the expression of transness can become, and what our expression of sex can become—without heteronormative boundaries, and instead an expulsion-of-tits-against-glass mind-blowing experience, what Yarberry refers to as the “festoonery of manhood” and the “stain of womanhood,” wearing gender as sexy campy costumes. Animalistic imagery both sharply pronouncing how trans bodies are often viewed, and reflective of the transness Yarberry’s speaker finds eroticism within:

“Here’s my naked chest (ooh-la-la).

Here’s my anatomical anonymity blushing in a burst of blue light!

Which is all to say, I framed myself in the window, grotesque

and chewy like another damn Picasso painting,

My nipples hardening against

the glass” (MEDUSA, 12).

Their speaker professes against the cisgender obsession with gender stagnancy, and equally, the narrative of hopping from one edge of the binary to another and conforming accordingly. Reinventing an overwhelming push for self-discovery, Yarberry urges a search for something less static: an exploration of our most innate— “It’s not that I became/anything. I was. I was” (TRANS IS LATIN FOR ACROSS, 88). It is a beautiful revolution to understand our gendered selves as disconnected from boundaries dictated by white heterosexual gender performance.

The speaker remains unwaveringly fascinated with ideations of self, both our publicized social behavior, and vulnerable private behavior, shared only with lovers and in solitude. In FANTASY, two independent stanzas share this ideology: while stanza one contains “normalcy, normalcy. I wore a shirt / with buttons. I spoke in boring / passages,” stanza two alleviates the self-preserving normative and replaces it with the exposed innards of the speaker. Stanza two remains uninterrupted by punctuation, containing “I see myself/with such odd precision/it shakes me and I shake out/all the bad things I’ve done to myself” (71). A heartbreaking truth: queer and gender diverse people stifling their exuberant transience to protect themselves against a cruel cisgender public. Yarberry’s concentration on the duality of the public versus private encapsulates what it means to exist in a gender-diverse body, as we continue to seek and find pockets of queer intimacy in the comfort of our private lives.

In this collection void of canonical romanticism, it is Yarberry’s skillful intention to lead us to a reevaluation—through the erotic—of the vastness of relationship dynamics beyond those forcefully dictated to us. This speaker is one who haunts, extracting our internal desire for belonging as our most vulnerable-queer versions of ourselves, begging for a humanity post-gender observation. Yarberry’s speaker leaves us with a definitive volta:

“It is nothing special

To not want to be hurt” (TRANS IS LATIN FOR ACROSS, 88).

Reading A Boy in the City, I feel myself relaxing into the easy chair of this dreamy futurity, free of heteronormative constraints on our multiplicity, and it is so comfortable.

Aja Leigh St. Germaine is a writer focused on queer and Native liberation. St. Germaine serves as the essays editor at Honey Literary, a 501(c)(3) BIPOC women and femme literary arts organization founded by Dr. Dorothy Chan and Dr. Rita Mookerjee. They student-edited Dr. Debra Barker and Dr. Connie Jacobs’ essays collection, Post-Indian Aesthetics: Affirming Indigenous Literary Sovereignty (Arizona Press, 2022), and is a Ronald E. McNair scholar. St. Germaine graduated Magna Cum Laude from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire in May of 2022, receiving their Bachelor of Arts in English Critical Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.

S. Yarberry is a trans poet and writer. Their poetry has appeared in AGNI, Tin House, Indiana Review, The Offing, Berkeley Poetry Review, jubilat, Notre Dame Review, The Boiler, miscellaneous zines, among others. Smith‘s other writings can be found in Bomb Magazine, The Adroit Journal, and Annulet: A Journal of Poetics. They currently serve as the Poetry Editor of The Spectacle; they also run a small magazine called Tyger Quarterly. S. has their MFA in Poetry from Washington University in St. Louis and is now a PhD candidate in literature at Northwestern University where they study twenty and twenty-first century receptions of William Blake. Their first book of poems, A Boy in the City, is out now from Deep Vellum.