The New *There*: The Politics of Access in Sherwin Bitsui’s Dissolve

The New *There*: The Politics of Access in Sherwin Bitsui’s Dissolve

Jay Deshpande

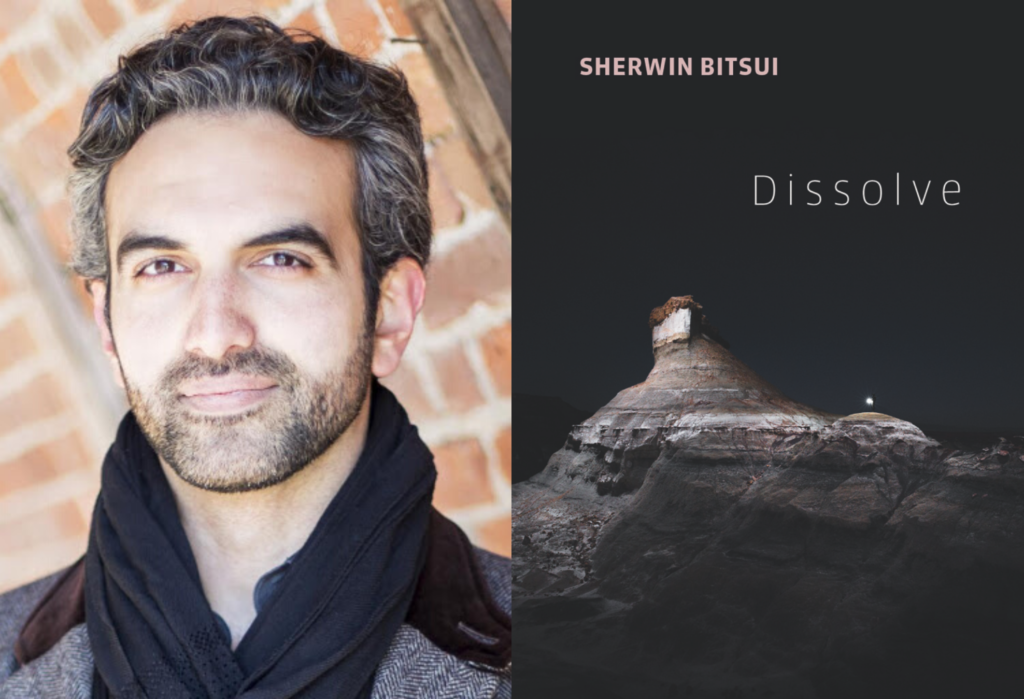

Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2019. 80 pages. $16.00

Reading contemporary poetry, we tend to treat the speaking I as the key to understanding questions of identity. But poetry can inhabit difference in more ways than the speaker or the assumption of autobiography: it can change our sense of access altogether. In his third book, the Diné (Navajo) poet Sherwin Bitsui takes an approach that is entirely his own.

I replace what I saw

with what I heard,

pull out a letter

sent from ourself to my selves

—and for a second

the flattened field is chandeliered

by desert animal constellations. (14)

Dissolve keeps the reader close to the page, tracing the slight adjustments that occur through a sentence. (How is the heard distinct from the seen? How does it relate to a self-addressed letter? And what is the significance of differentiating between a first-person plural and a first-person singular?) But often the experience is one of frustration: much like the field’s brief illumination, we discover a system of logic only for a moment before it collapses.

In his 2017 essay “Sherwin Bitsui’s Blank Dictionary,” Brian Reed explores a similar frustration in close-reading the poet’s previous collection, the American Book Award-winning Flood Song. Reed suggests that rather than rewarding “greater ingenuity, a reorientation to the nature of language, or immersive research,” Bitsui’s poetry highlights a difference between how it may be read inside and outside of Native American communities. “Non-Indigenous readers are permitted, even invited, to read such poetry,” Reed says, “only to have the fullness of its meaning withheld.”

One of the great gifts that Dissolve bestows is what it withholds. A reader like me has to live in the discomfiting experience of being on the outside. It’s not just that this work challenges me: it’s that it refuses to reaffirm my intelligence, or the rules of the world I live in, or the academic systems (of class, whiteness, privilege) that taught me how to read poems. Instead, Bitsui reminds me that there are other ways of experiencing language and world. I find myself bristling, uncomfortable, and indebted.

In texture and structure, Dissolve is an extension of Flood Song. Much like its predecessor, the book consists primarily of one long poem. Its sections are short and image-driven; they resist paraphrase but bear every sign of meticulous, confident crafting.

A lake, now a tire-rut pool,

leaves bitter aftertastes

on single-roomed tongues. (31)

Throughout the poem, an image is offered to the reader, then modified, then linked to another register of imagery altogether. Reading the sentence above, I picture a lake, then re-envision it as a pool of water in a rutted dirt road. I imagine consuming that bitter lake-become-pool. But then I trip over yet another modification: the tongue is “single-roomed,” which suggests the mouth as a low-rent habitation.

Bitsui’s image lexicon thrives on indeterminacy and change. The poem is full of mist, cloud, pollen, wind. These atmospheric nouns give texture and echo the Diné Bahane’, the Navajo creation myth. They are also ephemeral; they cannot be caught. Bitsui’s impulse is to shift between tangible matter and fleeting forms, so that one thing slips into another and we cannot tell where body ends and mist begins. In keeping with the book’s title, he reminds us to allow for passing experiences of language, the senses, or the metaphysical—nothing lasting, all of it mutable.

Covering its sobs with corral dirt,

I imagine a canyon floor,

cornstalks growing in rows

along a sunlit sandstone wall

in the far corner of a room late in life. (12)

Dissolve is landscape poetry, redolent with the American Southwest: canyons, trails, and open expanses. But it is also rife with imagery of destruction. Here are “maps of jet fuel residue” (38), the “hummingbird’s gassed lungs” (24), and evaporating lakes. The speaker witnesses the “uranium pond” (19) left by mining on Diné land, as well as the gentrification of natural resources: “This plot, now a hotel garden, / its fountain gushing forth— / the slashed wrists of the Colorado” (21). Yet with the “reservation spiraling back from the aftermath,” Bitsui presents a complex vision of history (10). In Dissolve, the past is ever ramifying into the present.

Notice: every link in the trail to here

is a bullet’s path to back there. (11)

Bitsui portrays a changing world of environmental collapse, but also one of intergenerational trauma: on the global scale as well as the familial one, we witness harm passed down and enacted over and over.

This temporal vision is clearest in “The Caravan,” a compressed narrative of addiction and self-destruction that precedes the book’s long poem. Bitsui’s speaker saves his alcoholic younger brother from outside a bar: “I’ve only rescued a sliver of him, / he’s only twenty-five / and he smells like blood and piss,” he says (5). The brother’s only comment is a repeated “one more, just one more”: he wants to keep drinking to destroy himself, yet his wish is for continuance as well.

Bitsui enacts this ambivalence toward time throughout the book. Although “an elegy hands me a busy signal” (11), this work feels inherently elegiac: how could it not be, when it speaks from the genocide of Indigenous peoples? How could it not be, when his language is ever pointing toward the Navajo tongue and what English fails to paraphrase? Suggesting that the elegy is occupied or insufficient, Bitsui offers an alternative discourse instead. By precluding a measure of access, he returns poetry to one of its most ancient functions: as a sacred space where profound transformation is possible.