REVIEW OF KATHRYN BROMWICH’S “AT THE EDGE OF THE WOODS”

By Lisa Grgas

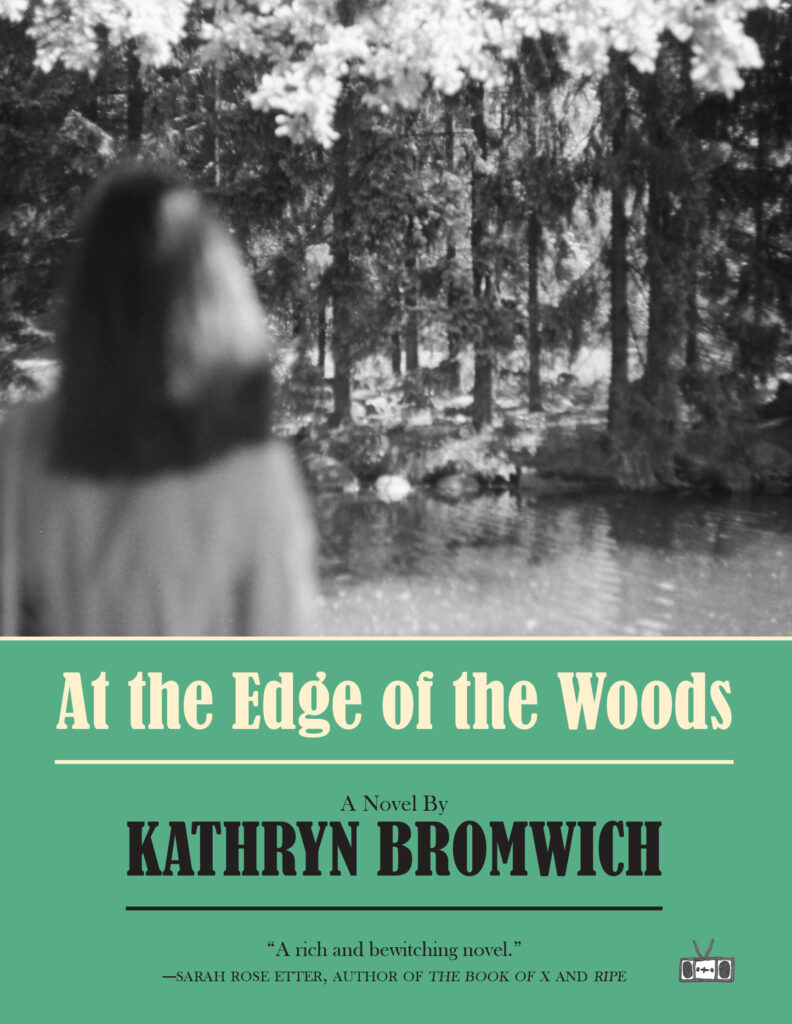

Bromwich, Kathryn. At the Edge of the Woods. Two Dollar Radio, 2023. $18.50

Kathryn Bromwich’s novel, At the Edge of the Woods, is a haunting and enigmatic debut from a promising new author. The novel follows Laura, a woman living alone in a cabin in the Italian Alps, as she struggles to rediscover her sense of self through a deep exploration of the rural mountainside and overindulgence in alcohol and drugs. Whether or not Laura is successful in her labor is questionable: she seems to have discovered something by the novel’s end, but hell if I know what!

At the Edge of the Woods opens with Laura’s description of her daily walk. She wakes before dawn, piles on layers of heavy clothes, and walks into the forest in the darkness. This first chapter is gorgeously written and highly descriptive. We are with Laura through the strain of the steep, first fifteen minutes of her walk, her blood pumping and sweat dripping even before “the first signs of light begin to glimmer in the sky, the starry blackness fading to a dark gray.” We are with her as she eats the first half of her morning pastry, and much later, when she eats the second half and feels it sit “warm and satisfying” in her stomach. We make it to the top of the pass, as she gazes “over the peaks, the trees, the lake in the distance, the gossamer clouds billowing out in bruises of blue and pink, purple and gold, the horizon a clear gleam like a lamp shining behind a pale yellow veil, branches snaking in front of it like the centerpiece of a stained glass window […].”

At the Edge of the Woods opens with Laura’s description of her daily walk. She wakes before dawn, piles on layers of heavy clothes, and walks into the forest in the darkness. This first chapter is gorgeously written and highly descriptive. We are with Laura through the strain of the steep, first fifteen minutes of her walk, her blood pumping and sweat dripping even before “the first signs of light begin to glimmer in the sky, the starry blackness fading to a dark gray.” We are with her as she eats the first half of her morning pastry, and much later, when she eats the second half and feels it sit “warm and satisfying” in her stomach. We make it to the top of the pass, as she gazes “over the peaks, the trees, the lake in the distance, the gossamer clouds billowing out in bruises of blue and pink, purple and gold, the horizon a clear gleam like a lamp shining behind a pale yellow veil, branches snaking in front of it like the centerpiece of a stained glass window […].”

But I am most interested in what Laura tells us about herself, in a glancing comment that she does not delve into more deeply:

Over time I have learned the path’s duplicitous ways – its thorns and unsteady footholds and half-seen creatures have become better known to me lately than my own reflection, which with the passing of the years has departed so much from the image I expect to see staring back that steeling myself to face it has become a daily penance, a source of horror so visceral and intense that for the ensuing minutes it taints all other considerations. But in the trees here there are no mirrors, or others in whose glances I can see myself reflected, only the astringent cold stinging my eyes as the soft sweet smell of growth and decay.

These lines stuck in my mind as the novel progressed. Laura has forgotten her own face? Her reflection is a horror from which she feels compelled to hide?

Laura, as the novel’s narrator, moves away from the topic of herself. She orders cured ham, tinned fish, eggs, bread, pastries, and two bottles of red wine at a village shop, but struggles to smile and make small talk. She heads home, unpacks groceries, and cleans herself up before taking a nap. Laura has irregular work translating documents on commission from the villagers, which occupies a few hours each day. Before delving into the subversive Gothic novels she reads for entertainment before bed, Laura obliquely mentions that she has poured herself “the first drink of the day, a glass of red wine that I sip little by little, letting its anesthetic effect wash over me in waves.” By nighttime, she is alone, her “mind loosened by laudanum and cheap wine” and feels “as though I have stepped over a threshold, passed from a place of dreariness into somewhere new, dangerous, that I don’t fully understand.”

At the Edge of the Woods is tremendously fun to read because Bromwich is so slick with her signals that Laura may not be a reliable narrator. Laura’s attention is honed in on the forest, her long walks, and anxiety about interacting with the villagers during routine chores. As time passes, she learns to “glance away and make [her]self still” when the birds and animals in the forest become aware of her presence. Similar instincts guide her when she visits the village: “I do my best to smooth out the more feral edges that have started to manifest in me […]. I endeavor to maintain a veneer of respectability: cleanliness, manners, a subdued manner toward men.”

Laura does not allow us much more than this glimpse into her motivations and anxieties. They exist, and that’s about all she is going to relinquish to us. Once Laura meets a dark-haired waiter, Vincenzo, at the village’s annual festival, our view constricts further: they drink, they overdo it with the laudanum, and they “spend hours stroking each other, not quite awake. Everything is heightened, exquisite: the quality of our jokes, the colors of the sky, the sensation of his hands on my body.”

At this point, Bromwich shifts narrative tracks entirely, taking us back in time to Laura’s life before she relocated to the forest. The plot becomes more stable and linear, and we learn what tragic circumstances brought Laura to her current state. The themes of infertility and restrictive social expectations of women become apparent here, as Laura approaches and evades her fear that her marriage has failed due to her inability to conceive a child. On the morning her estranged husband, Julien, is due to visit, Laura is “out of bed at first light” to begin her beauty routine:

I bathe, the water as close to scalding as I can bear, my skin softening and shriveling like a raisin infused in rum. I massage the ends of my hair with fragrant oil and wrap each strand into a tightly wound curl, which I fasten to my scalp and allow to dry. In the meantime, I apply depilatory cream to my upper lip, arms and legs; it tingles on my freshly scoured flesh, a sensation I never fail to find oddly gratifying.

When Julien is delayed without apology or explanation, Laura is filled with the “grinding numbness” of repeating the beauty ritual the next morning. Later, she tries to appease Julien’s foul mood at dinner:

I can’t explain why, after all this time, I still feel an obligation to please him. The fear of his reprimands alone, verbal or otherwise, does not account for all of it; part of me is still eager for his approval, if not his affection. His barely veiled contempt exerts a powerful hold over me, evoking a sensation that both electrifies and subdues me.

The dichotomies that arise in each passage (soft skin/scoured flesh; electrifies/subdues, etc.) are provocative, but, for me, aren’t the most compelling (or even most important) aspects of the book. What interests me is simply Laura: She decides to go into hiding in the forest for one year for logistical/legal reasons. But why on earth doesn’t she leave after the year is over?

I want to trust that Laura’s actions have a rational basis, that there is truth to her characterization of Julien, and that she has more than a flimsy toe-hold on reality. But her decisions don’t seem (on the surface) to be at all sensical. At the Edge of the Woods could be read through the lenses of illness, infertility, and societal expectations for women, though I chose to read it for the way it challenges ideas of self and non-self, reality and non-reality.

It’s perhaps because I preferred reading from a self/non-self lens that I was most affected by a section titled “INTERLUDE.” In this section, the narrative shifts from first to third person. It opens:

At first she sees only colors: a fuzzy succession of greens and reds and purples dancing together on the back of her eyelids, forming into one shape then another like fireworks or trails of slime left behind by snails on a window. She tries to follow them with her pupils, left, right, up, right, left, down, up, but for some reason they do not move, as if they were etched into her mind itself, disconnected from her vision.

“INTERLUDE” follows this unnamed “she” through wracking nausea and vomiting (“liquid is coming out of her lips, eyes, nostrils, every part of her; her limbs are on fire, an acerbic taste in her mouth, acid seeping through every pore”), fever, and hallucinatory dreams in which she flies up into the middle of the sky:

Free of weight, of pain; she is the air, the river, the mountain, and at that moment she realizes she is in a dream and cries out, because she knows that dreams cannot survive self-awareness, not for long, not truly, and while she grasps for this feeling to continue she starts to fall, her attempts to hold on warping the energy into something else entirely as she plunges through the night until she lands with a thud, and she is awake.

“INTERLUDE” colors the remaining sections of the book. I return to the line that “dreams cannot survive self-awareness” and that Laura grasps for this feeling to continue. It’s subtly tragic and suggests that, perhaps, this is not a novel about self-discovery. It may be a book about the dissolution or extinction of the self.

My impulse is that At the Edge of the Woods does not primarily grapple with illness, infertility, or societal expectations of women. Laura’s departure into the forest seems inevitable: she would have moved toward some version of the dissolution-resolution-dissolution cycle whether or not she was infertile and whether or not her marriage failed. Perhaps the villagers distrust Laura and want her out of the cabin not because she’s chosen a bizarre and socially unacceptable living situation. Instead, they may have picked up on a psychic instability within Laura that, rightly or wrongly, makes them feel increasingly uncomfortable. Laura, of course, can’t see this in herself because she is unable to acknowledge herself in any meaningful way. Pan out from Laura’s narrow first-person perspective: She is living in the woods, drinking too much alcohol, consuming too much laudanum, and has isolated herself from the village. How should the villagers have reacted to Laura?

By the novel’s end, Laura seems confident that she has discovered something essential, life-altering. (Whether or not she’s a suitable judge is uncertain.) Laura tells us:

I have read, somewhere, that a great deal of suffering might be spared if we were taught to expect nothing from the world in the first place. This had struck me as impossibly bleak at first, but the more I think of it, the wiser the proposition appears. I am done, at last, looking outward for meaning, or knowledge, or acceptance. The more I look into the world, the more I realize I will not find these things there; it is through my own consciousness, flawed and deceitful though it is, that all is refracted. […]. Like the spider, or the dreamer, I have weaved my life and now move in it.

Laura’s conclusion makes me giddy. Like the spider or the dreamer! Whatever Laura believes she has discovered, I hope it is not as sinister as it feels in my gut as I close the book’s covers. At the Edge of the Woods ends just as it should: obliquely, elliptically, asking us to trust, against our better instincts, that Laura is capable of handling what’s left of herself and of her life.

Lisa Grgas is the Supervising Editor at The Literary Review. Her work has appeared in or is forthcoming from Tin House Magazine, Adroit Journal, Whiskey Tit, Painted Bride Quarterly, Ki’n, Common Ground, Luna Luna, Black Telephone, and elsewhere. She lives in Hoboken, NJ.