REVIEW OF ADRIE KUSSEROW’S “THE TRAUMA MANTRAS”

By Nicole Yurcaba

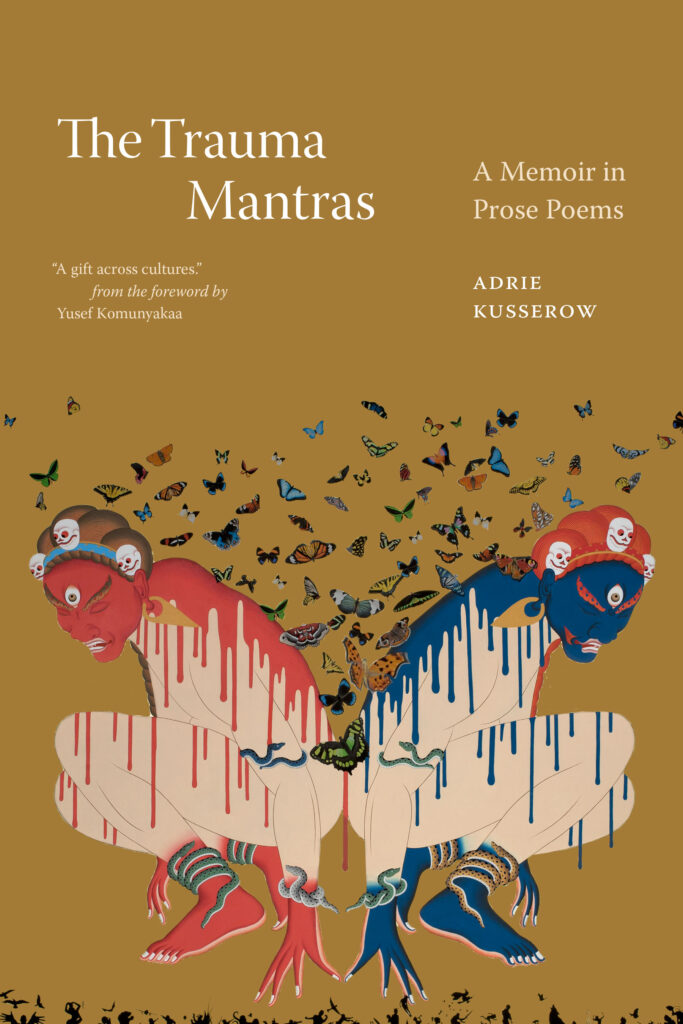

Kusserow, Adrie. The Trauma Mantras. Duke University Press, 2024. $19.95.

A Critique of Western Concepts of the Self, the Individual, Privilege, and Trauma: A Review of Adrie Kusserow’s The Trauma Mantras

In the poetic meditations which comprise Adrie Kusserow’s The Trauma Mantras, readers encounter challenges to American and Western senses of individualism and the self by exploring, in depth, universal reactions to trauma. Kusserow juxtaposes the experiences of Nepalese, Indian, South Sudanese, and Bhutanese refugees against the privileges and comforts of life in the United States. Kusserow’s book is the type of memoir that arrives and makes readers—particularly Western and American ones—necessarily uncomfortable. Thus, the book is a careful critique of American isolationism and a call for a widening of the American self and a clinical dissection of her own socio-economic and cultural privilege.

One of the main themes in The Trauma Mantras is that travel is the best educator. Kusserow depicts brothel raids in West Bengalese brothels, traveling treacherous roads in South Sudan, confronting American privilege in college classrooms, and teaching online safety in Bhutan. As Kusserow’s numerous travels unfold, readers understand that during Kusserow’s travels, she chose not to venture to Paris’s glitzy streets or London’s swanky halls. Instead, Kusserow chose a different kind of travel, one that required her to venture to the Earth’s far places that many Americans cannot name, let alone fathom traveling to. Her work with various governments and nongovernmental organizations led her into the real, frequently violent and gritty, lives of locals struggling for daily survival. Initially, Kusserow romanticizes the brutality she faces in these countries, admitting that she “imagined being part of those raids, rescuing kidnapped girls.” However, Kusserow makes a personal confession exemplifying how her travels and volunteer work in these areas made her realize and account for her American privilege: “This is a story of a story I wanted to be the hero of, but wasn’t. I wanted to tell it over and over, propping it up on prominent display back in the great USA, until I rose like an angel from my perpetual shame.” Thus, in as much as the book is a manifesto about the education travel provides, it is also a call for one to choose travel and work that leads them to understanding the real people who make a society tick and thrive.

One of the main themes in The Trauma Mantras is that travel is the best educator. Kusserow depicts brothel raids in West Bengalese brothels, traveling treacherous roads in South Sudan, confronting American privilege in college classrooms, and teaching online safety in Bhutan. As Kusserow’s numerous travels unfold, readers understand that during Kusserow’s travels, she chose not to venture to Paris’s glitzy streets or London’s swanky halls. Instead, Kusserow chose a different kind of travel, one that required her to venture to the Earth’s far places that many Americans cannot name, let alone fathom traveling to. Her work with various governments and nongovernmental organizations led her into the real, frequently violent and gritty, lives of locals struggling for daily survival. Initially, Kusserow romanticizes the brutality she faces in these countries, admitting that she “imagined being part of those raids, rescuing kidnapped girls.” However, Kusserow makes a personal confession exemplifying how her travels and volunteer work in these areas made her realize and account for her American privilege: “This is a story of a story I wanted to be the hero of, but wasn’t. I wanted to tell it over and over, propping it up on prominent display back in the great USA, until I rose like an angel from my perpetual shame.” Thus, in as much as the book is a manifesto about the education travel provides, it is also a call for one to choose travel and work that leads them to understanding the real people who make a society tick and thrive.

The book’s critique of American society—and by association, Western society— is what will make some readers shift uncomfortably in their recliners. Specifically, Kusserow focuses on America’s focus on mental health. She posits, “When America falls in love with a mental illness, it falls hard. Its devotion primal. It sees nothing else.” She asserts that America is “so busy triaging the individual, the collective gets forgotten, the mundane rampant poverty and inequality lack the same clout.” Because of this obsession with safe-guarding and protecting the individual with no regard for the overall collective, American society stands in very stark contrast to the other cultures featured in Kusserow’s book. At first, the critique might seem callous and harsh, but the question it poses—when considered in the context of the brothels, misogyny, and extreme poverty explored in the book—is perhaps necessary: what makes one person’s traumas more important than another’s?

Inherently, The Trauma Mantra is about the power of stories. The collection is a compilation of stories, and as the stories within each story weave together, readers see how intertwined humanity actually is. Readers see that human barriers, objectification, and borders compartmentalize these stories, creating a distinctive individuality that resonates with the American and Western elevation of the self and the individual: “Here in America, it’s different, your story needs to be special, but not enough to land you in a psych ward.” However, Kusserow provides readers with gentle reminders about placing one’s story above another’s: “Sometimes others’ stories multiply your own, sometimes they cancel each other out.” “Breathe With Me Barbie” exemplifies this, but it also shows the juxtaposition between America’s materialistic society and the community-oriented societies from which many refugees hail. As Kusserow interacts with Sudanese refugee girls, she notices that they are obsessed with Barbies, and she is forced to leave her “cranky feminist critiques behind and buy one anyway.” Kusserow adeptly weaves the girls’ history with details about their new, polished life which the Barbie represents. The girls play “personalized care at Mattel’s Barbie Wellness camp as they mimic makeovers and pedicures, practice identifying with Barbie’s sparkly pink feelings.” The Barbie doll, symbolic to American culture for decades, now becomes an object in which Kusserow’s story and the girls’ story overlap.

Interestingly enough, the book also tackles another subject relevant to modern society—the influence of technology. One of the most thought-provoking points about this appears in the piece “Mating Knot,” which occurs in Yei, South Sudan. Kusserow likens the mass of cords to “the writhing pile of snakes we saw near the river in a mating knot.” She considers the toll the group’s use of electricity takes on the “stick-thin, anemic country that kept getting pummeled with war.” The critique becomes immediate and personal as Kusserow observes her own daughter: “her fingers white knuckle gripped around her iPhone, her headphones on her pillow, the tiny sounds of Harry Potter skittering like mice into the vast Sudanese bush.” Another example of this is when Kusserow describes the students’ rush for the generator as a “competition,” and the generator becomes a spot where students “watched their laptop obsessively.” The reliance on technology is glaringly visible: “Even in the dim of moonlight, you couldn’t miss it, a vast T-shaped vein of electric current, mauled by the charging cords of NGO laptops and Iphones, a tangled nest of dozens of cords wrapped around each other, vying for the best spot.” Thus, while some of the book’s pieces openly criticize America’s obsession with pop culture and materialism, pieces like “Mating Knot” pose how technology, too, creates barriers that inhibit and limit the American and Western self by dividing them from areas of the world that are not technologically-dependent or obsessed.

The Trauma Mantras is necessary and immediate, especially as America and the West grapple with their duties and commitments to stalling climate change, helping impoverished nations, and progressing in a world that is more and more globalized by the day. It subtly poses questions about the role of the individual in a world that is increasingly interconnected. Thus, The Trauma Mantras challenges borders of all kinds and fictions—cultural, geographic, and personal—not to weaken society and the self, but to strengthen it.

Nicole Yurcaba (Нікола Юрцаба) is a Ukrainian American of Hutsul/Lemko origin. A poet and essayist, her poems and reviews have appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Atlanta Review, Seneca Review, New Eastern Europe, and Ukraine’s Euromaidan Press, The New Voice of Ukraine, Lit Gazeta, and Bukvoid. Nicole holds an MFA in Writing from Lindenwood University, teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University, and is the Humanities Coordinator at Blue Ridge Community and Technical College. She also serves as a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and Southern Review of Books.