Pleiades Book Review: Oli Peters on Rosa Alcalà’s “YOU”

By Oli Peters

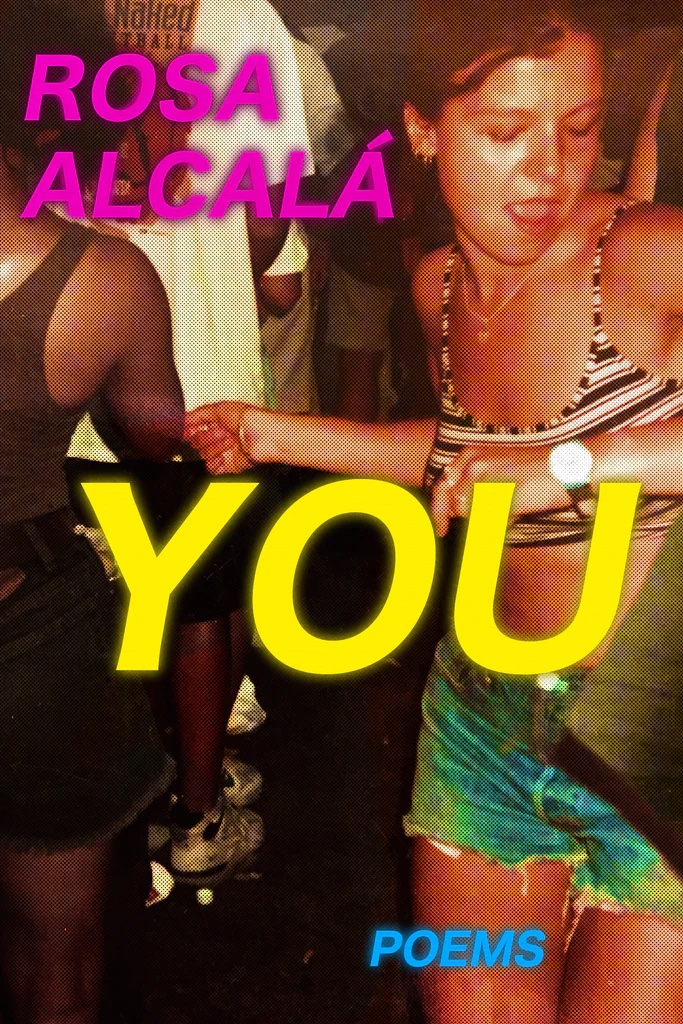

You. Rosa Alcalà. Coffee House Press, 2024. $17.95

Recently, a father told me of his daughter’s first catcall. She was confused. How could her body, walking down the street, listening to music, betray her like that? How could it elicit commentary so sharp that it pierced through her headphones? No noise-canceling device is strong enough to protect people from the publicity of their body in a world that sees it as an open invitation for others’ opinions, vulgarities, and vicious drives to strip it of its autonomy. In response to the father, I shook my head, said what a terrible rite of passage, hazily recalling the never-ending slew of crude words and gestures that have been flung at my body throughout my life. In You, Rosa Alcalà’s fourth book of poetry, she doesn’t just shake her head at instances of gendered violence, she grabs then shakes the head of the violator within intimate and purposeful prose poems.

Coffee House Press, 2024.

The poems in You create and move through a terrain in which bodies—their vulnerabilities, their cumulative wisdom—are at the forefront. This multigenerational, boundless molding of self also undulates through her last book: MyOTHER TONGUE. However, in those poems, language rather than body (if those two things can be divorced from each other) is the main interrogative thread. In another departure from MyOTHER TONGUE, Alcalà utilizes prose in this new collection, citing in her opening poem that she chose “sentences that don’t break” to “witness [her] body as a distant thing that gathers itself over time to become whole,” to seek “narrative logic to order the mess of memory.” These poems do indeed achieve a non-chronological placing of memory, memory that seems to belong to her, the bodies that created her, the body that she created (her daughter), as well as my body and your body.

Alcalà’s book hinges on the use of the second person: she calls upon you—the word and your own self—to signal that you are the yarn which weaves the poems together. Everything that she writes about, all of these instances of corporeal injustice, confusion and insight run through your anatomy as they run through the corpus of the book and the myriad lives and stories that it contains. As Alcalà writes, “the body is completely symptomatic of other bodies, including / its own.” She deterritorializes the boundaries of the body, developing a space of much-needed solidarity, at the same time that she recovers experiences in which authority was ripped from you.

In the poem “You & Louise Bourgeois’s The Fragile,” Alcalà considers the dismemberment of boobs from form. A man at the entrance to the Bourgeois show asks “‘Are they all boobs?'” In the next sentence, Alcalà writes that “yes, from the moment you are ten years old and a man remarks, Your garbanzos are swelling.” Another critic exclaims: “‘Look, a spider tit!'” And Alcalà reacts:

You want to either strangle him or whisper firmly ‘Kneel before what is holy.’ And while he is on his knees, tell him how you come home eager to fold your arms behind your back in a silent prayer that is the unclasping of the bra…to meditate on the image of your nipple popping out of your baby’s wet lips as she falls asleep, like roulette wheel’s pointer. How the nightly ritual erects a feel-good invisible fence that zaps the memory of lip-smack and heh-heh-heh.

Moments like these are not only a reclamation of the parts of you that have been sexualized and misconstrued and shamed, but a re-authoring of what those parts mean. The definition of the boob, of Bourgeois’s multivalent, layered art pieces, is not an inert object that’s activated by someone else’s crass, grossly simplistic interpretation. Your body vibrates with you, which is a perspective of sacred personal and intergenerational experiences. The world denies you of this cogency again and again. But if another can see the whole of you, then a space is carved in which “the gentle lips of your lover kiss each nipple good night.” Yet even still, “the cut of his teeth keep them awake.”

Alcalà also discusses the body as a zone that contains the history of countries (ones you belong and belonged to, ones your relatives and ancestors did). You can grasp and remodel that history, as exemplified in the poem “Your Daughter Refashions the Flag into a Crop Top.” It begins: “The frayed flag of a disputed territory that barely covered your sex: the thing woven onto you, the thing you had to accept.” She writes that this flag was snipped by vicious, careless people with scissors as Yoko Ono’s clothing was snipped in her performance “Cut Piece 1964.” Then “to your daughter you bequeath what was left of the flag, and rejecting its unflattering form, she refashions it into a crop top to show off her midriff.” Here, country and flag appear as an instruction of the body. And if those instructions fail you, then you can still aim to create a world in which your daughter (who is also you) is able to take the tattered fabric and forge it into a piece of clothing that does justice to your form, that allows you to move through the world as you choose.

The poems that constitute the body of You act as this crop-top flag. They reorient and redefine our current landscape, which is one that grossly underprotects a multitude of bodies and genders. Alcalà dives into events of inhumanity and emerges with a history of survival that’s radiant and essential. Now that I’ve read You, what else would I say to the father whose daughter got catcalled for the first time? I’d say that they should both read this book.

Oli Peters is a MFA candidate at the University of Notre Dame. Her most recent work appears in New World Writing and Heavy Feather Review.