Language, Desire, & Navigating Different Worlds: Esperanza Hope Snyder in Conversation with Ruben Quesada

Language, Desire, & Navigating Different Worlds: Esperanza Hope Snyder in Conversation with Ruben Quesada

Esperanza Hope Snyder is the author of Esperanza and Hope and co-translator, with Nancy Naomi Carlson, of Wendy Guerra’s poetry collection, Delicates. She is the recipient of scholarships and fellowships at the Gettysburg Review, the Kenyon Review, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Latinx Writers’ Conference in Albuquerque, and the Community of Writers. She is the Assistant Director of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Sicily and co-coordinator of the Lorca Prize.

Snyder’s debut poetry collection, Esperanza and Hope (2018), is a remarkable exploration of a woman’s life who experiences events in threes – a holy trinity. The collection is divided into Colombia, Europa, and Estados Unidos. Snyder’s writing is captivating as she skillfully captures moments of beauty, like her vivid depiction of “my grandmother, lake Guatavita, with a whole town immersed inside her.”

Snyder was born in Bogotá, Colombia, and her childhood was shaped by her father, whom she describes as constantly changing and toxic. Her mother moved the family in with her grandfather, who shared his love of poetry with Snyder. One of her elegies, “Lorca and My Grandfather,” is included in the first section.

Green are the words in my grandfather’s mouth,

Green his emeralds, green the veranda in his house.

He put his fingers in his vest pocket, unfolded

Paper squares and triangles for emeralds,

green like mountains.

At twelve, Snyder lived with her aunt in Atlanta and then with her father in Wisconsin a year later. Finally, at fourteen, she moved to Maryland to reunite with her mother and brother. The collection’s second section is filled with poems celebrating the splendor of art, history, and love during Snyder’s time as a student, wife, and mother in Europe. Titles like “Arranging Flowers,” “Salamanca, Summer Sundays,” “IL Mio Marito Italiano,” and “Chiaromonte, For Phil Levine” offer a glimpse into her life during that time.

The collection’s final section deals with the upheaval of moving to the United States as an adolescent and becoming a passionate poet. As a literary journalist and scholar, it was a privilege to interview Esperanza Hope Snyder in February 2023. Our interaction took place through a shared document.

RUBEN QUESADA: Espe, I am familiar with your poetry collection, Esperanza and Hope, and I admire your skillful use of language to convey a clear and expressive voice. “Candle,” in the collection’s final section, describes the speaker’s return to her father’s home in Wisconsin after his death to collect his ashes.

This is the closest I ever came

to loving him, standing in his empty room,

looking through his things, learning.

The speaker’s estrangement from her father is clear from the start. By the poem’s end, while begrudgingly scattering his ashes, she changes her tone about her father. The ashes of her father coalesce with nature.

Last spring, to please my husband, we went

to the river, poured my father, one scoop at a time,

on the towpath, on the bluebells, in the water.

RQ: I’m excited to learn about your new poetry collection. What themes, techniques, or influences can you tell me about?

ESPERANZA SNYDER: First, I want to say that I admire your work and am honored to talk to you about poetry. My new collection continues to explore themes from Esperanza and Hope, like childhood, relationships, language, place, and belonging. However, I’m now focusing on how identity and relationships change over time and how these changes impact the speaker in the poems. For example, while Spanish was my first language, English is now the language in which I write.

RQ: Can you tell me more about how language plays a role in your new collection?

ES: Language has always been a means to communicate. Poetry helps us build bridges between languages, cultures, and opinions. Poetry is the universal language. In my new collection, I’m exploring how language reflects changes in identity and relationships.

RQ: That’s fascinating. Can you give me an example of how this plays out in one of your new poems?

ES: One of the poems in the collection, “Immigrant,” expands on the fraught parent-child relationship explored in “Candle” from Esperanza and Hope. The new poem also explores the love the speaker seeks from her absent father and the acceptance she desires from those who live in her father’s country of origin. This place has now become her home. The diction in each poem changes according to what the daughter/child/adult woman attempts to communicate.

Because my US Passport was the only thing

my father left when he left…

I held on to the document and what I thought

it meant: that I was loved, that I was wanted,

that I was good enough for him, for them.

RQ: That’s a great example. How does your approach to language and identity relate to your personal experiences?

ES: As someone who speaks Spanish and English, language has always been a way for me to navigate different worlds. I speak Spanish with my family and English with my children. I’m exploring how language reflects these different aspects in my new collection. How does this shift reflect how I view the world? About how I express my ideas and my feelings?

Do I revert to my childhood while talking to my mother? Does speaking English to my children make me a better parent, or did I cave by using the dominant language while raising them? Would I have better relationships with people if we spoke only Spanish?

RQ: The relationship with your children is central to your work. I’m reminded of the cover of Esperanza and Hope, which is a painting by Francisco de Zurbarán titled “The Education of the Virgin” that portrays, among other things, the relationship between mother and daughter. Does art influence your new work?

ES: My new collection includes a section titled “Thinking About John Suazo’s Sculptures” which consists of several poems inspired by Suazo, who lives and works in Taos, New Mexico. Several years ago, I was privileged to visit John in Taos and interview him. When John’s stories and his sculptures inspired me to write “Mountain,” “Salmon,” and other poems, I drew from my practice of ekphrastic poetry and poems like “Santa Madre Tierra: Gente Mezclada” which appears in Esperanza and Hope. This poem was inspired by the story of a fresco in Santa Fe, commissioned by the president of Saint Johns College and painted by artist Frederico Vigil in a building on the college campus. After Vigil completed his work, a group of faculty members and students demanded that the fresco be covered. They claimed they were offended by some of the themes Vigil’s fresco explored and the nudity. (Vigil had depicted Mother Earth giving birth). One evening, a student broke into the building, destroying Vigil’s fresco with an ax. I met Vigil at the National Cultural Hispanic Center during the Latinx Writers’ Conference when he was working on another fresco in El Torreon, on the center’s campus, and he told me the story. My experience writing about this fresco, which continues to live solely in the artist’s memory, prepared me to write the Suazo poems inspired by his sculptures.

ES: Can you tell me more about the story of La Segua and how it relates to your work?

RQ: Sure, La Segua is a legend from Costa Rica that I adapted for modern readers in my work. The story tells of an Indigenous woman who was wronged by a lover and condemned to wander the streets. She appears at night, her face obscured by darkness, and the legend contains frightening undertones. “Segua” comes from Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and means “woman.” Mythology like La Llorona from your poem “Childhood Companion” is comparable. La Segua was the first bedtime story I ever heard. I learned the legend of La Segua and other folktales from my maternal grandmother.

The legend of La Segua can be traced back to archives and manuscripts from the early 16th century. According to one version, an Indigenous woman was wronged by a lover and condemned to wander the streets. The legend tells of a woman who appears at night, her face obscured by darkness. The word segua derives from Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and means “woman.” Nahuatl is an oral language that should be spoken rather than read. These stories contain frightening undertones. Today in Latin America, disparities in the quality of life between light and dark-skinned people persist.

ES: That’s interesting. Can you talk more in detail about the poems in your chapbook from The Offending Adam?

RQ: The chapbook spans Jane’s life from 21 in 1966 and spans 80 years of her life. I’ve started writing from the perspectives of several characters in Jane’s life, including her best friend, ex-husband, and lovers. These poems are fable-like, emphasizing sound in the manner of a ballad’s oral heritage. Some poems are based on actual incidents to keep readers grounded in reality. For example, “Jane (1967)” is about her encounter with a film team while walking on the upper west side. The song “Sympathy for the Devil” by The Rolling Stones plays in the background.

ES: That’s really unique. Could you share more about your writing process?

RQ: I draw inspiration from my personal experiences and research about my family’s history. I also incorporate elements from different mythologies and legends that I find intriguing. I want my work to be worthwhile and meaningful for readers, and I believe incorporating other stories and perspectives is essential to achieving that.

ES: I love that your maternal grandmother’s folktales and your mother’s family history inspired you to write Jane/La Segua. I find the level of complexity in the poems captivating, with the mixing of everyday occurrences and supernatural images. Verses in the book’s first and last poems beautifully capture life stories and myths. In the first line of the collection’s opening poem, we find this strong image:

A divorced woman rich with misfortune

robed in silvery rococo silk stands…

The final poem brings to mind the myth of Daphne and Apollo; we find nature and the supernatural:

…To be set free

from this tree, one would need the Godspeed of an angel.

In the second stanza of the first poem, we read these verses:

…when from behind a darkling vine through the Rose

of Sharon Bushes, an eagle’s talon dives down

Which I believe are echoed in the last two lines of the final poem in the collection:

…In this grim tree

is a wicked banshee or a welcomed pet to a single eaglet.

ES: I would like to hear more about the role that you think desire and fate play in our lives. Do you believe in fate? Does desire interfere with destiny, or does it help?

RQ: Thank you for noticing these trends. Some believe that everything is predetermined and that we have no control over our lives, but others believe that we have free will and can alter our fates. The reality falls somewhere in the middle. While certain occurrences are preset or fated, we still have some control over how we respond to them. In these poems, fate is a compelling narrative element. It highlights Jane’s desires and motives, and it has the potential to be a positive force.

RQ: Speaking of desire and fate, the opening of your last collection offered a remarkable narrative essay that revealed a vibrant life full of desire. Do you have any plans to write a memoir?

ES: I’ve been working on a memoir, trying to figure out the best way to tell the story. I’m thinking about adapting it into a novel. Several years ago, I wrote a play, The Backroom, about an ambitious, idealistic woman who wants to save her country. Director Anthony Nardolillo expressed interest in adapting it into a film. I’ve enjoyed collaborating on the screenplay with writer/producer Oscar Torres and look forward to seeing the film one day. It would be great if the memoir/novel also became a film. But first, I plan to give birth to my new poetry collection and send it out into the world.

RQ: Thank you for agreeing to have this exchange with me. You’re an extraordinary thinker and poet. Fate brought us together, and I look forward to reading more of your work.

ES: Thank you, Ruben, for your close reading of my work and for sharing your powerful poems with me.

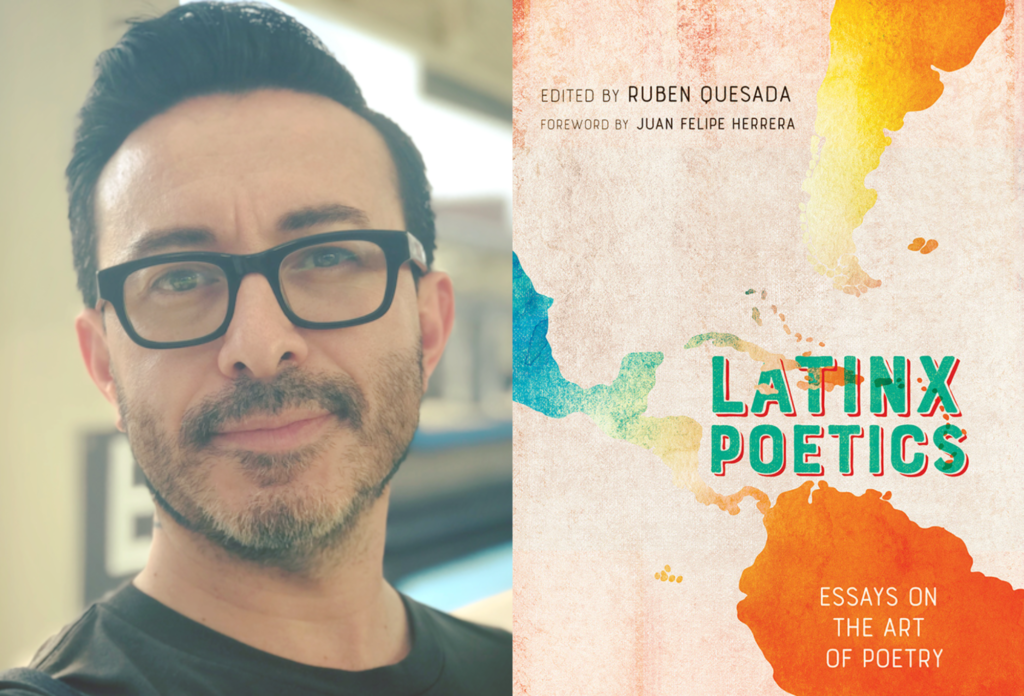

Ruben Quesada is the editor of Latinx Poetics: Essays on the Art of Poetry (2022). He is the author of Jane: La Segua (2023), Revelations (2018), and Next Extinct Mammal: Poems (2011). His writing appears in The New York Times, Best American Poetry, American Poetry Review, Kirkus, and Harvard Review. He teaches in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Antioch University-Los Angeles and for the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program.