Jacques Rancourt on Writing the Excessively Gay Book

This is a guest post from poet Jacques Rancourt. If you’re interested in contributing a guest post, please email me at m [dot] salesses [at gmail etc]. –Matthew Salesses, Website Editor

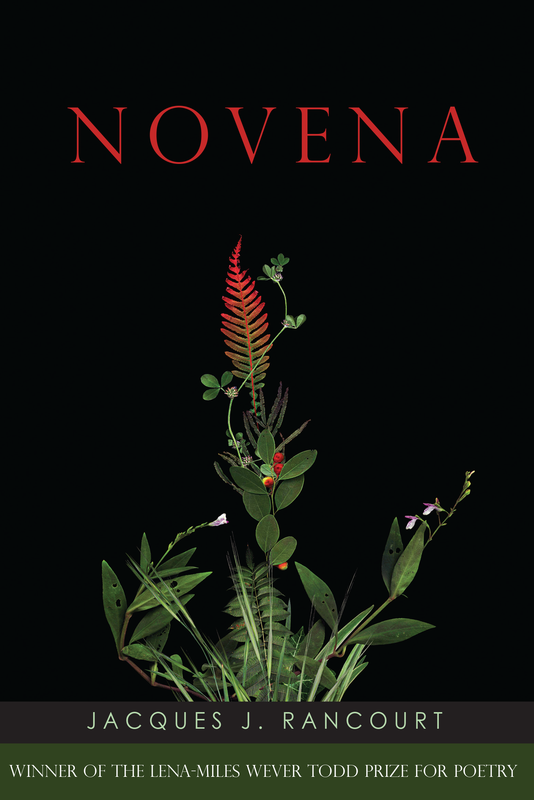

Jacques J. Rancourt is the author of Novena, winner of the Lena-Miles Wever Todd prize (Pleiades Press, February 2017). He has held poetry fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, and Stanford University, where he was a Wallace Stegner Fellow. His poems have appeared in the Kenyon Review, jubilat, New England Review, Ploughshares, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Best New Poets 2014, among others. He lives and teaches in the San Francisco Bay Area.

In poems inspired by and sometimes borrowing their forms from the novena, a nine-day Catholic prayer addressing and seeking intercession from the Virgin Mary, Jacques Rancourt explores the complexities of faith, desire, beauty, and justice. Novena is a collection that invites prayer not to symbols of dogmatic perfection but to those who are outcast or maligned, LGBTQ people, people in prison, people who resist, people who suffer and whose suffering has not been redeemed. In Novena, the Virgin Mary is recast as a drag queen, religious icons are merged with those who are abolished, and spiritual isolation is scrutinized in a queer pastoral.

* * *

Writing the Excessively Gay Book

While still revising my first book, Novena, I swapped manuscripts at a coffee shop with another gay poet whose work I admired. His advice: tone it down.

“Your book is too gay,” he said. “You don’t want to pigeon-hole yourself in your first book.”

He meant well. He asked me to consider the careers of other queer poets—poets who were successful, but who might have been really successful had they been more subtle about their material. He was trying to get me to think of those readers I would be alienating, who would be shut out by my raunchy gay poems. He asked me to think about a more open-ended address in my poems, and to veer away from the queer “him.” Consider the difference, he offered, between Carl Phillips and Mark Doty.

Some months later, another gay poet and I exchanged poems. “I like these,” he told me, “but they feel like they could have been written in the 1990’s.” He meant that the violence they encountered, the physical threat to the speaker, doesn’t exist in the 21st century anymore. Walking through the woods, we got into a debate about whether or not gay men could consider themselves as a minority these days.

***

Perhaps why this advice—or rather, this way of thinking—rang false for me is that it didn’t reflect the America I grew up in.

Where I grew up in rural Maine, in a nearby town called Bethel, a man who was two years older than me—Scott Libby, who friends of friends all seemed to know—was murdered after making sexual advances on another man in a hotel lobby. Libby was strangled with a belt, his head beaten in by a cast iron pan. His dead body was then put into his own car, driven to the train tracks, the ignition turned off, the car left, where later that night it would be hit by a train.

The motive for the murder was declared “gay panic.” Despite that the blood on the suspect’s cast iron pan matched Libby’s, in fall of 2009 this suspect was found by a jury to be not guilty.

***

I recently gave a reading at a university in rural Missouri where afterwards the undergraduate who introduced me asked how does one go about writing queer sex poems that are explicit in their sexuality without becoming too graphically crass. My advice was to make his poems more graphic and explicit, more gay, not less. It made me think how, when I was his age, shortly after deciding not to discern for the Catholic priesthood, I read Becoming a Man by Paul Monette. That spring, in 2006, I reread over and over this passage:

“Until the cramps were so bad, I excused myself and wobbled downstairs to the common loo. I sat on the can, and a great slug of his cum exploded out of me. I stared between my legs at the water, the milky swirl of life. And felt a kind of emptiness and shame deeper than anything I’d ever known. As if I aborted the dream of my own manhood, or coughed at the wrong moment and missed the line in the play that would have made everything right. But that’s probably more than you want to know.”

How well I recognized, at nineteen, that emptiness and shame. How much it meant to me, that dose of explicit and graphic reality that subtleness could only betray. There was a comfort to that familiarity, a comradery and solidarity between myself and this man who had died over a decade earlier. Its vivid and disgusting detail—how can I explain this?—carried me through the darkest months of my life; it spoke to me the way people never did.