Inside the Squirtle Shell: Taxonomy, Vulnerability, and Black Boyhood in Marlin M. Jenkins’ Chapbook, “Capable Monsters”

By Rita Mookerjee

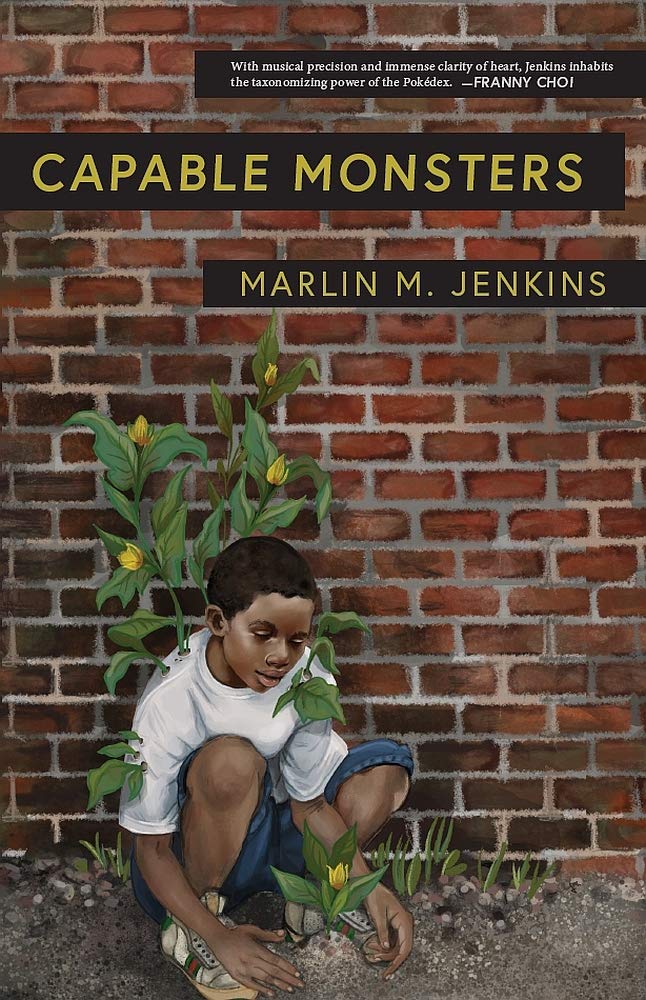

Capable Monsters, Marlin M. Jenkins, Bull City Press, 2020. 41 pp. $12.00

“They’re not going to be worth any money,” my mother sighed as I unsheathed a new pack of cards, sliding them carefully from foil. I didn’t care; money was never the point. At ten years old, I was entranced by the horrors and curiosities presented to me through the world of Pokémon. There was nothing more profound than the idea of ghosts, demons, and dragons that could live by my side, protecting me from harm and inspiring me to do my very best each day. I am 31 now and proud to tell you that it wasn’t a phase. When I am not grading gender studies papers, I explore the Crown Tundra in the latest expansion of Pokémon Sword on my Nintendo Switch. As such, it will be no surprise that I deem Capable Monsters by Marlin M. Jenkins a bold, experimental work that investigates youth, Blackness, power, and protection using the Pokéverse as both an organizational tool and a backdrop rich with allegory.

Jenkins undergirds this collection by titling poems in the encyclopedic style of Pokédex entries complete with short factoids about Pokémon behavior and habits. Like the Pokédex database itself, Jenkins is concise. His taut, manicured lines result in beautifully spare and biting poems that impart weathered maxims and private revelations alike. While various fantasy creatures slither and amble through the writing, Jenkins grounds the book in America’s material reality. There is consistent attention to anatomy in this text, particularly about the shared physical properties of Pokémon and Black people that get perceived as shocking, aberrant, or dangerous.

Using the fantasy realm, Jenkins conjures images that are startling and wholly unfamiliar. In doing so, he captures the transient nature of Black boyhood with all its beauty and brutality. In “Pokédex Entry #1: Bulbasaur,” the speaker finds himself inside of the small, green Pokémon easily identified by its vine-like appendages and the large growth that sits like a shell on its back. This growth, the speaker reveals, encapsulates deep ancestral trauma, “[an] awful nourishment” that calls forth both life and death. The back has long been recognized as a corporeal site of pain in Black lived experience and history. Perhaps the bulb marks the child speaker as a descendant of Toni Morrison’s Sethe whose savage bouquet of whipping scars healed to resemble a chokecherry tree. There is violence in this poem, not just because of the past, but also because the speaker visits the doctor where he must catalogue his family’s medical history within a space that has proven hostile to Black people for centuries. The speaker feels both “awesome and visible,” accepting his legacy and allowing the proverbial seed to “grow, sprout, open,” however painful that may be (“Pokédex Entry #1: Bulbasaur”).

Through in-game world-building along with films and TV series, Pokémon fans observe how people’s relationships to Pokémon are complex and change over time. Many disapprove of the franchise for its use of violence and domination. For example, a common ideological criticism of Pokémon is that it effectively normalizes animal abuse and disrespect for nature. There are also those (real and fictious subjects) who believe that competitive battling is unethical and that people and Pokémon should instead strive for symbiotic living. Rather than sidestepping such critiques, Jenkins leans into these points of tension and expands them beyond the world of the game. Indeed, it is hard to ignore the ugly parallels between Pokémon catching and hunting and poaching. These acts of violence and exploitation also correspond to the history of colonization and the advent of chattel slavery. In “canon,” the speaker explains:

a trainer is not a trainer / without something to train / without the monster he finds / in the grass who struggles / against him until caught / tamed forcibly befriended / (and similar what is an oppressor / without the oppressed)

These haunting truths are not comforting, nor should they be. Rather, they are reminders of how quickly curiosity can morph into aggression or something far more sinister. Reminders like this one also appear in “some theories on origins.” The speaker wonders who exactly authors the Pokédex, a seemingly all-knowing textual resource:

ash asks the Pokédex for nomenclature / it tells him what everything is / and he believes it (“some theories on origins”).

As he thinks of the “trainers breeders battlers researchers [and] fashionistas” whose firsthand accounts inform the massive database, we can see why this sort of epistemological question is crucial to our understanding of history and critical race theory. Jenkins calls attention to who gets to tell the story as well as who listens to the story once it has been told. “some theories on origins” also lays bare the power of naming. Broadly speaking, Pokémon communicate by speaking their own names aloud, often accented by growls, squeaks, or chirrups. The result is a kind of self-knowledge punctuated by the utterance itself. In the final stanza, the speaker discloses that:

in large crowds I think / I hear my name and I know not / what to say except / to shout it back (“some theories on origins”).

Connecting this idea to the first poem in the collection, our names and nicknames often carry with them memories, secrets, and legacies. Children often practice writing their own names or wear name tags at school. In Capable Monsters, we see how much weight the act of naming carries.

Flanked by noble Pokémon both great and small, Jenkins’ speaker yearns for safety. Capable Monsters exposes the mythic nature of childhood innocence, a luxury seldom afforded to Black youth. Jenkins urges the reader to ask, “What does it mean to feel safe and sound? To be safe and sound?” As the sobering dedication to Atatiana Jefferson reminds us, safety is never the default for Black people in America. Jefferson was murdered by a police officer while she was playing video games with her nephew. How many other Black children have had their games interrupted, their laughter stolen in a flash of racist violence? Perhaps it is for this reason that Jenkins concludes Capable Monsters with a poem about the elusive Fairy-type. Fairy Pokémon are uncommon making up only 63 species out of the near 1000 monsters in the Pokédex. Fairy-types are often associated with sweetness, love and music. Clefairy, for whom the final poem is named, is believed to be from the moon. This Pokémon’s otherworldliness makes it somewhat unknowable, except to others of its kind. With this concluding piece, Jenkins makes a wish for a mountain sanctuary far away from white oppression:

only returning / to our rest, gathering / in each other’s names / in caves and mountains / where you can’t find us, / holding each other / tight and forever (“Pokédex Entry #35: Clefairy”).

This masterful blending of dark and ethereal typifies Jenkins’ poetry. Childhood is a time to treasure and be treasured. Jenkins illustrates this throughout Capable Monsters stressing the power of play and imagination for Black children in particular. His work reminds us to hold space for our ghosts and demons but most of all, for our sacred younger selves.

Rita Mookerjee is an Assistant Teaching Professor at Iowa State University. Her poetry is featured in Juked, Hobart Pulp, New Orleans Review, The Offing, and the Baltimore Review. Rita is both the Sex and Poetry Editor at Honey Literary as well as the Assistant Poetry Editor of Split Lip Magazine, and a poetry staff reader for [PANK].

Marlin M. Jenkins was born and raised in Detroit and is the author of the chapbook Capable Monsters (Bull City Press, 2020). He studied Creative Writing and Black Studies at Saginaw Valley State University, and studied poetry in University of Michigan’s MFA program. His poetry has been given homes by Indiana Review, TriQuarterly, Waxwing, Iowa Review, New Poetry from the Midwest, and Volume 2 of Oxidant Engine’s BoxSet Series. His fiction has been given homes by The Rumpus, Passages North, and the anthology Forward: 21st Century Flash Fiction. He has worked as a teaching artist with Inside Out Literary Arts, teaching poetry to middle schoolers in Detroit Public Schools, and was an editor for HEArt Online’s Let Me Love Me section, which was dedicated to poets of color writing about body image and self-love. Before moving to the Twin Cities in Minnesota, he was an occasional bookseller, a Lecturer at University of Michigan in the English Department Writing Program, and the fiction instructor at the Neutral Zone–a teen center in Ann Arbor. His favorite pokemon is umbreon.