Choking Toward Life: Beth Ward on Didi Jackson’s “My Infinity”

By Beth Ward

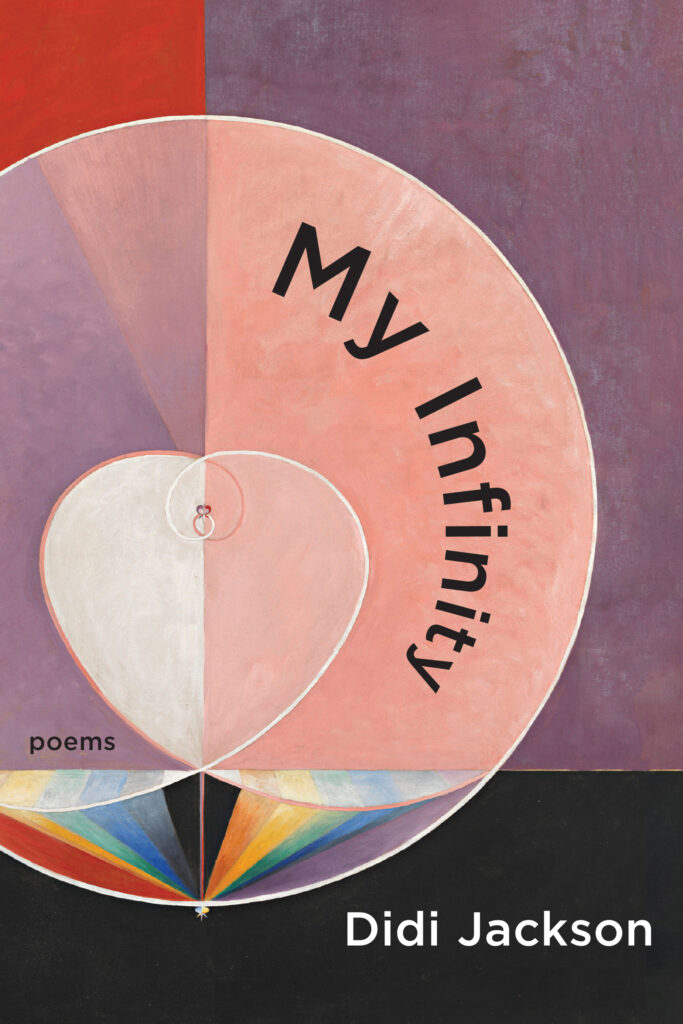

My Infinity. Didi Jackson. Red Hen Press, 2024. $17.95

Someone, somewhere once referred to Saint Prisca, or Pricilla, as “the one who wouldn’t die.” According to legend, this young girl, baptized by Saint Peter, was ordered by a Roman emperor to make a sacrifice to the pagan god Apollo. When she refused, men beat her and sent her to prison. Threw her to the lions. But she did not die.

Prisca was later starved. Men tortured her on a rack, sent her to burn. Still, she wouldn’t die. She choked toward life. Toward God. It would take a sword, a violent beheading, to finally kill and then canonize her.

In the opening poem of her latest poetry collection, My Infinity, Didi Jackson alludes to the child martyr’s life and her death.

Jackson begins,

At this hour, on this day, in this place,

in this exact light, the birch leaves shimmy;

how they clap at the sun with their gilded hands

like images of early Christians in the ancient catacomb frescos

of Santa Pricilla, these trees too raise their open palms

to pray, then settle, bask in the late afternoon glow.

What were those early acolytes praying for in the catacombs, a reader wonders? What knowledge, by which we might also say mercy, did Pricilla have to offer—that they were so desperate for to her bestow—that they would press their hands in prayer and beseech a 13-year-old girl? What answers could gilded birch branches possibly need from the sun?

Jackson goes on,

…The Green Mountains

Flex their muscles and like an old horse’s withers

twitch with a little wind. They must knowsummer is closing. It is their secret;

I am good with secrets.

If you bend the meaning of a secret, you might consider it a piece of knowledge that you aren’t meant to have, but do. Secrets are proof that perhaps you’ve seen something that you shouldn’t see. A secret is a thing you bear. A secret is a knowing, and a wanting to know.

This, then, may be the centrifugal pull tugging readers down, and in, and through all five sections of My Infinity. A need to know an unknowable thing. A hunger to know. To classify. To name. To access the inaccessible. To clap your empty palms in prayer and petition a formless god, or a birch tree, for answers.

Red Hen Press, 2024.

What sacrifices are we willing to make to get the answers we seek, these poems ask us? In the face of unspeakable loss, what old versions of ourselves and our lives are we willing to martyr to new gods to gain clarity and peace? What are we willing to consider, to believe, in order to access that knowledge beyond knowledge? To know what grief knows?

Martyr, we know, comes from the Greek, means “one who bears testimony to faith,” or “one who willingly suffers death.” Etymologically, martyr means “witness.”

We must look, Jackson seems to be telling us in these opening poems. At beauty, and death, and violence; at the birch tree, the butterfly, at our own soft bodies. At the mundane and the miraculous. At the peaks of those Green Mountains, the ones in which Jackson “lost my late husband’s mind / soon to follow was his body by his own hand.”

We must look again, and again, and keep looking. Surely, surely, there are answers there.

***

“I’m another woman hungry and ruthless for knowledge” Jackson writes in the first poem of the book’s second section.

These are the Hilma af Klint poems, the artist, seeker, and mystic whose work decorates the collection’s cover, whose sigils separate the book into its five parts, whose disembodied voice haunts, and narrates, and reverberates through some of My Infinity’s most potent works. Jackson’s incantatory verses call af Klint back from somewhere beyond us, creating, in many of these poems, an iambic chorus of two.

Af Klint was a Swedish artist and spiritualist whose pioneering abstract paintings are some of the first of their kind in Western art. Part of af Klint’s process was making contact with spirits or guides she called the High Masters through séance, trance, and automatic writing. This was a way of living and art-making triggered by the death of af Klint’s younger sister in 1880—this idea that one could be in direct communication with what they’d lost, that the dead were never really dead, that her own body was a vessel through which spirits might make contact again, come back and be near.

Af Klint was also creating work at a time when the unseen in the realms of science and medicine were suddenly made visible: X-rays enabling us to see inside the human body, infinitesimal atoms cracking open, offering us glimpses inside the universe. Af Klint’s art, both diagrammatic and sensual, cellular and spiritual, speaks directly to these mysteries, these secrets—of both the great beyond and the great right here.

When Jackson lost her first husband to suicide, her poems began doing this same work. She explored it in her first collection, Moon Jar, but that clawing search for answers, that longing for access to where the dead go, is present and pulsing through this section, too, and all of My Infinity.

In “The Automatic Writing of Hilma af Klint,” Jackson writes as an imagined, incorporeal Hilma, declaring, “I wanted to see the invisible.”

For af Klint, a woman equally interested in mathematics and mysticism, this likely meant both the tiniest machinations of science and nature, as well as the grand mysteries of the spiritual world, the world of her High Masters, the world where her sister now resided. Jackson seems to have found a kindred spirit in af Klint—she, too, using her art to try and make meaning, make contact.

Like af Klint, what Jackson thought she knew before the death of someone she loved shattered like light through a prism or sun through birch branches, her grief catalyzing in her a yawning need for a truth she could pin down like butterfly wings.

In the ekphrastic, “Tree of Knowledge,” Jackson writes,

Like Hilma, I want to decode it all,

but I’ll never know why

I was left a widow

In much the same way as af Klint, we can see Jackson’s poems as both a kind of altar to her dead and evidence of her continued contact with them as she lives and heals.

***

Like the lemniscate referred to in the title, My Infinity’s later poems end the collection near to where we began it—with Jackson paying an almost holy kind of attention to the world as a way to try and see beyond it.

Some of the collection’s most affecting, arresting work is done in these last poems, when we find the speaker visiting a medium in Cassadaga trying to communicate with her late husband, “parting with the sun like a Greek oracle” on Hawk Mountain, sitting in a circle of women trying to contact the dead.

The speaker in the later poems knows

now how / to look for signs,

those pagan symbols

on tree bark and in bird song.

In “Two-Headed Woman,” an opus, Jackson gives us something cacophonic, a poem seemingly filled with the choric voices of women we now know from the poems preceding it—Santa Pricilla, af Klint, and now Lucille Clifton, too—and maybe all women who, like Jackson, have tried to leverage their grief and their hunger to see beyond the veil.

She writes,

Even Lucille couldn’t ignore

the ancient calling to place the planchette

down over the letter G on the wooden Ouija board,

the spot to begin the separation of skepticism and belief.

The images we get in this poem reverberate through the body like a struck bell.

…And at that moment, I imagined the wind

picking up, a spoon or two

dropping from the counter in another room,

someone shouting fire as the twigs in the ash pit

spark and spit, her face not hot from the flames

but from all she learns, that knowledge

like a pearly white tooth

gnawing at her from the inside out.

We get a feeling here of something almost known, but not quite. The frustration of almost making contact, but not quite. Something almost being seen before dissolving into shadow. But we also see in these final poems Jackson begins to transmogrify this grief, this searching, this frustration, into something like awe. We see her martyring herself before the impossibility of ever knowing the thing she most wants to know, while accepting the fact that she may never stop looking for it.

As a poet, as a witness, Jackson trains her eye on everything, her continued seeking, seeing, in the face of death and loss a quiet and relentless refusal to die, to succumb to sorrow. In the poems in My Infinity, in her pursuit for both answers and absolution, Jackson chokes toward life, toward new love, toward something adjacent to whatever we call God.

“A ghost rests in my arms and I rock him,” she writes in the collection’s final poem.

for a moment as he remembers what was

good: the cool nights, the warmth of campfire

the mercy that strips us naked to each other.

Beth Ward is an award-winning essayist, editor, and critic writing about books and art, bodies and place, feminism and folklore. She focuses primarily on women’s histories and women’s stories. Beth’s work appears widely in publications including Oxford American, Hyperallergic, the Rumpus, Pigeon Pages Literary Journal, NPR, the Bitter Southerner, Atlas Obscura, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in narrative nonfiction from the University of Georgia.