A Croatian Novel for New Times: A Review of Ivana Bodrožić’s Sons, Daughters

By Damjana Mraović-O’Hare

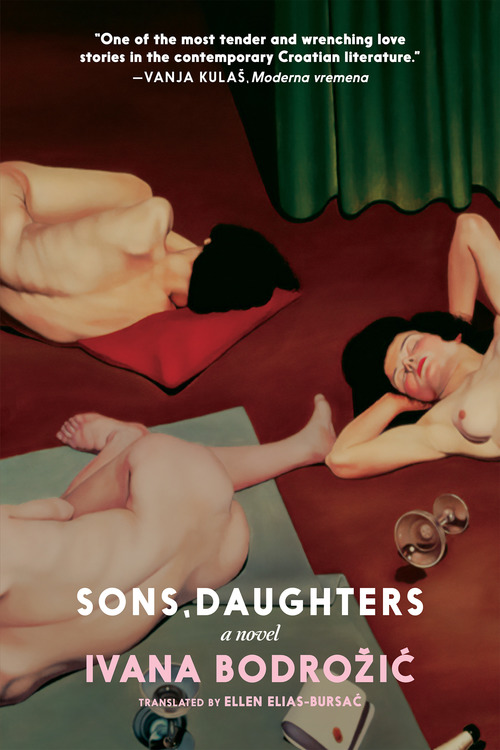

Sons, Daughters. Ivana Bodrožić. Seven Stories Press; April 2024. $21.95.

“It’s a hit-and-miss,” was a recent explanation of LGBTQ+ tolerance in Croatia. The statement was uttered during an official conversation about the country, surprising all who have been lulled by praises about Croatian EU membership, the economy, and the country’s breathtaking nature, which was not tarnished by the civil war of the 1990s. Ivana Bodrožić, who is considered an enfant terrible of Croatian contemporary literature and one of a few Croatian writers present in international markets, uses that point as an inspiration for her newest novel, Sons, Daughters.

Seven Stories Press, 2024.

In fact, she writes “In place of Acknowledgements, an Apology” to “all those who are forced to live, invisible, . . . to all those who were forced to live in Croatia during the adoption of the Istanbul Convention, and especially to those who have systematically suffered violence.” In 2013, Croatia signed the Convention that prevents and combats violence against women and domestic violence and ratified it five years later, but the Council of Europe found last year that its implementation should be more thorough and systematic. In that sense, Sons, Daughters is a book that exposes daily obstacles that the Croatian transgender community in particular faces, while domestic violence is presented as a consequence of a deeply rooted patriarchal behavior.

Bodrožić has earned the status of a supposed provocateur with her first novel, The Hotel Tito (2010). The book is semi-autobiographical, based on her experiences as an internal war refugee who lost her father during the Croatian civil war and was relocated to a village famous as the birthplace of the Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito, whose death initiated the disintegration of the country and the beginning of the clashes. In the book, she is exceedingly cynical about patriotism, establishment, and education. Above all, she is sarcastic about the capital Zagreb and its supposed intellectualism that is utterly disinterested in individualized consequences of the conflict yet insists on warfare. We Trade Our Night for Someone Else’s Day (2016) caused an uproar with its sweeping criticism of the Croatian post-war rhetoric, politics, and institutions that are seemingly rooted in war heroism but are actually driven by corruption, bribery, and self-interest. The book is written in a fast-paced, narration-dominant journalistic style that blurs the line between the fictional and factual but allows the Croatian reader to recognize public figures engaged in political scandals behind her characters. In a young country such as Croatia that is still constructing its identity, Bodrožić’s political fiction is challenging and unique but, paradoxically, welcomed as well. All her novels won a series of national awards, though she is somewhat perceived as a corrective of the country’s nationalistic and religious discourse.

Sons, Daughters is divided into three segments narrated by three different characters: Lucija, Dora/Dorian, and Lucija’s mother. The first-person narrative sections are introspective soliloquies that also form the narrative arc. Lucija, whose chronicle opens the novel, is in a palliative care hospital suffering from lock-in syndrome. While she cannot move her body—except, vertically, her eyes—she analyzes her upbringing and life, trying to explain a suicide attempt that brought her to the clinic. Cisgender Lucija is in a relationship with Dorian, a transgender man, but the internalized societal expectations and norms cause feelings of extreme shame and, ultimately, lead to her suicide attempt. The attempt is triggered by a misconception: Lucija thinks that her suddenly ultra-religious brother, who participates in anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns organized by the Catholic Church on the streets of Zagreb, recognizes her while she is with Dorian. The thought of being identified as a trans-person’s lover causes a nervous breakdown and she drives her car onto the tracks in front of a fast-moving train. This part of the novel is reminiscent of one of the best Croatian novels of the 20th century, a classic that is included in the high school curriculum, The Springs of Ivan Galeb by Vladan Desnica. In Desnica’s meditative and essayistic novel, the musician-protagonist recovers in a hospital after surgery, recalling his childhood and discussing art, death, and religion. The opening scene, in which bedridden Lucija notices the light in her hospital room, is evocative of Desnica’s opening in The Springs, while some of the most accomplished parts of Bodrožić’s text are those that establish a direct relationship with Desnica’s novel, such as the descriptions of the items on the nightstand or the ceiling that is the only thing the immobile Lucija can see.

In the second segment, Dorian provides details about his transition, but also about Lucija and their relationship. He is presented as thoughtful, open-minded, and exceedingly patient with Lucija’s bouts of self-doubt and crying episodes. His attempts to visit Lucija in the hospital are thwarted by Lucija’s mother who thinks he is younger than Lucija and therefore an inappropriate partner for her daughter. (Ironically, it seems that Lucija is not aware of how Dorian is seen; his gender identity consumes her understanding of his appearance as well as his character.) The focus of Dorian’s narrative is on the procedures of his transition: changing his documents, mastectomy, and a mandatory visit with a psychologist before his medical change. His status as an outsider in both the conservative society and the relationship with Lucija is repeatedly reinforced and yet he is the most stable character of the book.

The final section narrated by Lucija’s mother serves as an explanation of the culturally induced long-standing animosity both toward women and LGBTQ+ community. Lucija’s mother is overly protective of her daughter although the relationship with her is nearly pathological. In the first part of the novel, Lucija describes her mother as exceedingly critical of her own appearance and habits, manipulative and malicious even though the daughter is 30 years old. Lucija also finds her judgmental and conservative and is resistant to her mother’s presence to the point of a physical altercation. However, the mother in this chapter explains her behavior as a mis-manifested care: not only was she systematically subjected to the patriarchal demeaning of women but there was also a history of violence in the family. Married very young, Lucija’s mother saw a savior in her equally immature husband, only to have her dreams crushed after the wedding. Financially strapped, he decides that they will live with his family in a presumably rural environment, in a house with a domineering mother-in-law, an alcoholic father-in-law with incestuous dispositions, and without hot water. Despite having a job, Lucija is forced to hand all of her wages to the mother-in-law, supposedly for the upkeep of the house, which stays damp and disheveled. In that house physical abuse of her children starts, and the mother-in-law even convinces the son to volunteer in the war emphasizing his supposed patriotic and religious duties: “It would be a disgrace for them to come after you and march you off to jail. This is your country.” Expectedly, the untrained son is badly injured and despite a long time spent in a war veterans hospital, he eventually kills himself. The disintegration of the family that started before Lucija’s birth is complete, whereas the family history of mental issues and self-harm continues, presumably, never to stop. Emotional relationships, correspondingly, are marred with identity issues, acceptance attempts, and a quest to belong: to the nation, to the family,and to oneself.

Like in her previous novels, Bodrožić argues that the historical predisposition—as well as bigotry and traditionalism—are so deeply embedded in Croatian society that even the possibility of a change is perceived with utmost pessimism. She writes that society in general insists on a “scalpel for normalcy,” whereas its record is “A history built on wooden beams of the gallows, on torture devices, in concentration camps, gas chambers, ouster to the very edge of the society.” She is particularly critical of the older generations for embracing the war rhetoric and subjecting their families to a series of tragedies that, paradoxically, affect their offspring more than those who propagate the conflict. In Sons, Daughters, out of seven men killed from Lucija’s father’s unit, four commit suicide. The civil war, similar to Bodrožić’s previous novels, is a threatening background of her narrative, and partly the reason for the society’s conservatism.

Ellen Elias-Bursać, an established translator from Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian into English, provides yet another excellent transformation of a text written in a non-dominant European language. She has translated both of Bodrožić’s previous novels as well, skillfully navigating her prose and exposing its political urgency.

Dr. Damjana Mraović-O’Hare focuses on American contemporary literature, as well as literature of the successor states of the former Yugoslavia. She teaches at Carson-Newman University, TN. She is a Fulbright Scholar.