AN INTERVIEW WITH SERGIO TRONCOSO

Rey M. Rodríguez

An Interview with Sergio Troncoso

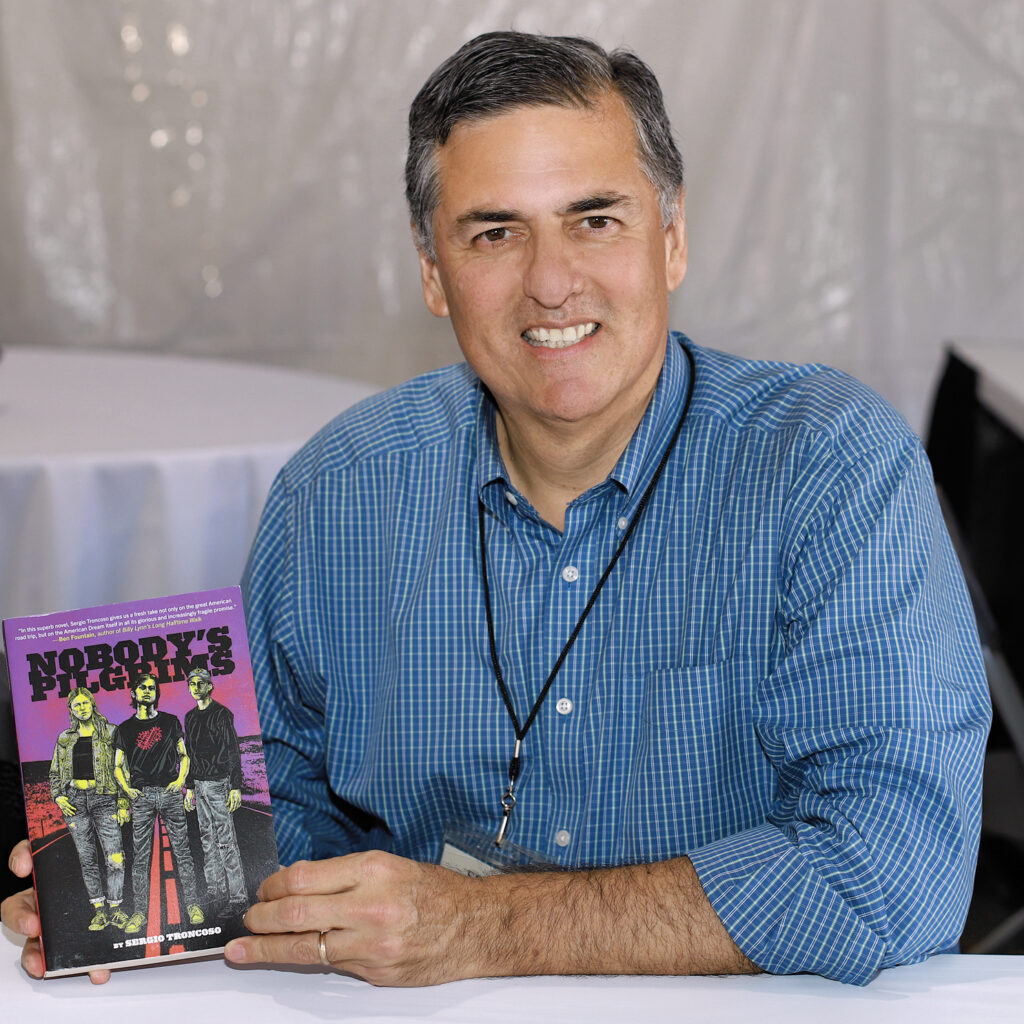

© 2022 Larry D. Moore. Licensed under CC BY 4.0

Sergio Troncoso was born to Mexican immigrants in the Ysleta neighborhood of El Paso, Texas. The family lived in a colonia near the border in a house that Troncoso’s parents built, without electricity or running water for their first two years in Ysleta. He is a Chicano writer, and more broadly a U.S. writer, who deserves to be widely read and studied. He attended Harvard and Yale universities. This journey from Ysleta to Cambridge and New Haven was not an easy one, but it is one that we all benefit from especially if we read and enjoy his many books and essays. Below is a wide-ranging interview with him from his early beginnings to his book, “Nobody’s Pilgrims,” Aristotle and Plato, the current state of Chicano literature, and what is next for Sergio Troncoso.

_________

Welcome, Sergio, would you mind introducing yourself?

I’ve written eight books. I grew up in El Paso Texas and I teach at the Yale Writers’ Workshop.

What moves you to write?

Well, do you want me to start at the very beginning?

Yes, let’s do it.

I was always writing as a kid, especially in high school. In 1979, I became editor of the Ysleta High School newspaper, the Pow Wow. Ysleta is a little town on the outskirts of El Paso, Texas. I seriously started writing in Ysleta. I was writing what I would consider the real topics that affected high school kids. Drugs in school and teenage sex. I also wrote, for example, about an undocumented immigrant who was hit and knocked to the ground by an immigration officer with his vehicle. The undocumented man was trying to escape. The incident happened on the Border Highway behind our high school, and my father was a witness to it. He knew I was an editor, he told me what happened, and I wrote about it. I interviewed the director of INS in El Paso. The immigrant had crossed the border on a little bicycle. He was peddling away from the green INS truck. The driver couldn’t apprehend him so he hit him with the car, instead. The impact knocked the man to the ground and bloodied him. The INS officer picked him up and threw them in the back of the truck, as my father said, “like a sack of potatoes.”

How did you investigate this case?

As part of the reporting, I interviewed the head of the INS in El Paso, and eventually, the border patrol officer was fired. Then The El Paso Times, which should have been investigating these types of cases in the first place, interviewed me. I gravitated to things that were happening in the neighborhood. I didn’t shy away from controversies or from writing about things that other people overlooked. I learned from experience that writing could be something important. When people got angry at me for my writing, when I created change with my writing, that’s when I knew writing mattered. But my writing had to be true, the stories people ignored, and the topics that were not necessarily popular. (By the way, I donated the issues of my high school newspaper, along with many boxes of photos, literary drafts, videos, and audio files, to The Wittliff Collections in San Marcos, Texas, where my literary papers are archived.).

Who inspired you to write?

My grandmother on my mother’s side, Doña Dolores Rivero, was very important to me because she was this tough older woman who was the matriarch of the family. She was more macho than anyone else in my family. During the Mexican Revolution, the teenage Doña Lola, according to family lore, shot and killed two men who attempted to rape her.

I felt that people should know who she was and what her values were, because these values were very important to me. Honesty. Righteousness. Fighting for the poor. Defending yourself against abusers. She was a great oral storyteller. She would be in her tenement apartment in El Segundo Barrio on Olive Street and tell stories for hours, deep into Saturday night. I would spend Saturday at her apartment, and she would recount violent and exciting stories about Francisco Villa and the División del Norte in Chihuahua. I learned oral storytelling from her, and for me, these nights were always magical under the desert stars.

On my father’s side, my grandfather, Santiago Troncoso was editor and publisher of El Día, the first daily newspaper in Juárez. When he retired, the city even named a boulevard after him. I only had a few lengthy conversations with him, but he knew that I wanted to be a writer. During his journalism career, he was jailed 28 times and his print shop firebombed two or three times, because he wrote anti-corruption articles against politicians and the Mexican government. Before I left for college to the Ivy League, his advice was “Don’t become a writer, because if you tell the truth people will hate you forever.” Any writer knows he’s right in a way, especially when you write about taboo subjects or other ‘hard truths’ in fiction. But I didn’t listen to him. He lived a very colorful life fighting for freedom of the press in Juárez.

Can you paint a picture of Ysleta?

My neighborhood of Ysleta was on the outskirts of El Paso, Texas, and initially it wasn’t part of the city. Ysleta was also right on the border with Mexico. I could walk to the Río Grande from our adobe house in about ten minutes. When I was growing up, the Zaragoza International Bridge was a tiny, two-lane bridge that you could walk across to Waterfill, Mexico to get groceries or to have a flat tire fixed. That part of the Lower Valley was a rural area surrounded by cotton fields full of snakes, horse farms behind our house, and irrigation ditches to water the fields. When I was a toddler, Ysleta had dirt streets and adobe houses with kerosene lamps because we had no electricity and an outhouse in the backyard. Water lines had not yet been connected inside homes. We moved into our house with plywood still on the windows because hoodlums were stealing the copper piping. So, my father and mother finished our house room by room while we lived there.

Eventually Ysleta was incorporated by the city of El Paso, which introduced city services such as water, sewage, electricity, and paved roads, but it took a couple of years before that happened. The main roads into our neighborhood, I-10 and America’s Avenue, were not far from my house, and those roads connected you to the Zaragoza International Bridge. Now that international bridge is a diesel-truck hellscape, a total of ten or twelve lanes going into Mexico and back to the United States, in which you could easily get caught in between twenty eighteen-wheelers rumbling into Juárez. Gigantic warehouses of many American manufacturing companies replaced the cotton fields of Ysleta. The import-export mania was not happening back then.

Why do you write about the Mexico/US border?

Because it matters that this community has a voice. I have a moral obligation to write about it, to be one of those voices that focuses on the complexity of the border. It matters that characters like Doña Dolores Rivero and people who are like my family and our neighbors, that these people are represented in literature, that their questions get attention, that their lives are portrayed in characterizations that go beyond stereotypes, beyond easy reductions of good or bad. By paying careful attention to people from Ysleta, or a place like Ysleta, I want these people to be lifted up and understood. Anyone who is struggling to survive in a chaotic, dangerous world would do well to read a character like Doña Lola. The border and its people have much to teach the rest of the country about the importance of bilingualism, living in between worlds (the concept of ‘nepantla’) and creating a multi-faceted existence that fights against nationalisms on both sides.

Ysleta and the border community are poor and often overlooked by the American mainstream. I think the basic motivation for me as a writer was to show why someone like my abuelita was important to understand. She could teach you how to survive a tough social situation. Are we entering a United States in perpetual crisis because we can’t come together as a country, with factions that hate each other? The Mexican immigrant values that I write about from my parents are first about self-reliance, that is, learning to do things for yourself. You do your own drywall. You put up your own adobe house. You make do when you don’t have anything. You dig your own sewer trench, which was taller than my brothers and I were and could have easily collapsed and killed us. But it didn’t. We survived. I think one of the things I learned from Ysleta is to be very independent and to work extremely hard to achieve anything, even the very basics of life. But even after you achieved these basics, you still helped your neighbors, you still pushed to educate yourself, you still found new goals to conquer. These values are forgotten when you end up too rich and satisfied in the well-developed neighborhoods of New York, Chicago or Seattle. Mexican immigrants—those who fight for their place in the United States and those who don’t assume their place because of generational privilege—represent the best of America. Their values are important values for everyone.

Okay, so let’s talk about “Nobody’s Pilgrims.” Can you give me a sense of why you wrote this book?

The novel is the story of outsiders trying to find their place in this country. Three teenagers are in search of their American Dreams: Turi, who is Mexican-American from El Paso; Molly, a working-class white girl from Steelville, Missouri; and Arnulfo, a Mexican undocumented teenager. These young people don’t really belong anywhere. They don’t even belong with their own families, but they belong with each other. Through a gauntlet of danger, as evil people are chasing them for the contraband the teenagers unwittingly carry in their truck, they form a community of three. They travel from El Paso, Texas to Kent, Connecticut to find a new home where they belong.

Why do you have these three teenagers face so many challenges?

They do face a lot of challenges and dangerous situations. I wanted to show character and how it develops through action. I wanted to show what happens when young people are faced with evil people about to harm them, or faced with a person who wants to deceive them. How do they respond? How do they get out of the situation? Who saves whom at different moments? And why? I wrote Nobody’s Pilgrims to show the resilience and grittiness of youth. I believe in young people. I get a lot of hope from them, especially from my two sons, who are fighting for what they believe in. I think young people are open to others who may be different from them, and they may form new alliances with others who are different from them, which is something very powerful and necessary today. It’s an adventure novel about how people become who they are, through these first experiences.

An orphan, Turi is a 17-year-old who lives in the back of his little house in Ysleta. Over time as you read the novel, you’ll see he goes from a sense of love as an abstraction to love as a connection with a particular person, even if that person is on the surface very different from him. He has a crush on Miss Garcia, the high school librarian. She is older and of course has no interest in Turi, but she loves that he’s a reader. So, she constantly feeds Turi books. This relationship helps him when he meets Molly. Turi connects with her and creates a very strong bond with her when he meets her in rural Missouri, trying to escape from evil people. There are many hidden philosophical questions and issues in the book. How do you develop character? How do you morph from idealism to realism as you move into adulthood? The book addresses racism, as well. Along the way some people are welcoming to Turi and Arnulfo, but others are racist and xenophobic. They don’t want Mexican Americans or Mexicans living in this country. How do you keep that racist poison from infecting your soul as you are faced with this kind of hate? Turi has to fight for his place in this country rather than to assume he belongs. He has to survive here, and he’s not turning back. Connecticut is where he’ll make his stand. Nobody’s Pilgrims is a thriller. It reads very fast, but it’s also my Aristotelian literary project, in a way. Sometimes it scares people when you mention you are writing philosophy in literature in a novel, but I like addressing basic truths while also telling a story that’s exciting.

How does Aristotle play in the book? I know you studied philosophy in graduate school at Yale.

It is not obvious, but as I mentioned Aristotle’s philosophy plays in this story. I like the idea of going from abstract ideas to ideas based on reality and practice. That’s the basic issue between Aristotle and Plato. It is about trying to understand how an abstract idea found in a book on Connecticut in an Ysleta library can propel this poor Mexican American kid from El Paso out of a horrible family situation. For Turi, reading propels him to look beyond his circumstances. It forces him to imagine another world because he’s an orphan. His extended family doesn’t want him at their house. He’s getting physically abused by his uncle. So, it is good that he has this idealism as an escape, but the ‘America’ he imagines is very different from the reality he encounters once he arrives in Connecticut. It’s all about having a Platonic idea of what you think America is, or a Platonic idea of what we think a partner should be, but then we have to work on what the reality is of our actual existence, how you make a life with a particular person. You have to go through life and difficult situations. The basic Aristotle retort to Plato is that a good person is not formed in the head by what they do at critical moments. For Aristotle, a good person is formed through action, in practice. These teenagers are helping each other. These teenagers are acting for each other and sacrificing for each other. When they respond to difficult situations, that’s when they find out who they really are.

How does the book’s title, “Nobody’s Pilgrims,” emerge?

Many years ago I was asked to give the White Fund Lecture in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The lecture was established by Judge Daniel Appleton White who was a contemporary of Thoreau and Emerson in the mid 19th century. Judge Appleton White founded the Salem Lyceum. These lyceums were some of the first public libraries in which people would donate books so that knowledge would be made available to the public. It was a place to study for people who didn’t have money to go to Harvard or Yale. So, this judge gave money to develop this lecture and it’s given in Lawrence Massachusetts. Past speakers include people like Junot Díaz, Ernest Hemingway, Julia Alvarez, and others. Today Lawrence Massachusetts is a majority Central American, Mexican, Dominican, Latino/a community.

I researched Judge Appleton White. As a Harvard alum, I went to Harvard’s Widener Library and found White’s memoir. It was written in the mid-1800s, and he’s complaining, among other things, about the rich people of Massachusetts and how they were treating newly arriving immigrants. He reminded them that their ancestors were English pilgrims, also immigrants. Many of these English pilgrims who founded Plymouth Colony and Jamestown died of starvation or may have participated in cannibalism because life in the New World was so difficult. In the mid-1800s, the new immigrants were English, Irish, and German. The rich who had already made it in New England wanted to shut the door to these new immigrants. As I read the memoir, I immediately recognized this story, which has repeated itself over many American generations.

Judge Appleton White criticized the New England elite for not helping these new immigrants. He thought we should be educating them. These immigrants, like any new wave of immigrants, I believe, represent the values of hard work and self-reliance that founded this country. From White’s memoir, I made the connection in my lecture to the scapegoating that Latin American immigrants face today. This is an old, cyclical story in which people make it here and then they decide to close the doors behind them. The story is repeated whether you’re English, Irish, Jewish, or Latin American immigrants. But these new immigrants, whoever they are, should remind those already here, what it took to make it in America, what desire burned in these immigrants to never give up, and what kind of hope these newcomers had, despite the dangers. These are the best American values.

I wanted to write about the new pilgrims of this country — nobody’s children. These people—like Turi, Molly, and Arnulfo—who represent the best values of this country. The values of trying to make it on your own. The values of fighting for your place. The values of helping each other. These are the basic values that started this country and served as its foundation. But too often we have forgotten them, and where these values came from.

And this working to become American, to find your place, instead of assuming your privileged place, this is Aristotle through and through. For Aristotle, you need to work and to act to find meaning in the idea of the good. An American who is growing fat and happy in Dallas, or anywhere else, will not have that practical, in-the-trenches Aristotelian understanding of what it takes to belong after a long struggle, like a new immigrant.

What is it like to be a Chicano writer at this moment?

I think we’re having breakthroughs after a very long struggle of trying to get attention, but it’s still not enough. It never really is enough. We always need to open doors for the next generation of Chicanas and Chicanos telling different stories than what we told. We definitely have a few more places that will publish us regularly. We also have conferences and get-togethers in which Chicanos can get together and talk about each other’s work, but it’s not enough. I think also the community is changing. Our readership is changing. I have seen the emergence of this growing Mexican-American middle class, and that is changing what they want from literature, what they want to read. Mexican Americans are getting educated, with more getting master’s degrees and Ph.Ds. At the University of Texas at El Paso, for example, the entering class passed an interesting threshold a few years ago: for the first time, less than half of the entering class was from households that were the first in their families to go to college. In a university that’s about 80-85 percent Mexican American, that means college-educated Mexican Americans are now sending their kids to college. This is an important milestone. We are educating our community, and we need to continue this march to education, because that’s how you gain power. In many ways, “Nobody’s Pilgrims” was written for my children—Aaron and Isaac.

These new generations will be asking very different questions than the questions I asked, when I felt like a complete outsider in the American literary establishment. We are still outsiders, but we’re getting more people to succeed in the literary world, with bigger contracts and more support from the publishing world in New York. The struggle never really stops. I would encourage all Chicano/a authors to help the next generation. They must help young people by not only encouraging them to read books, but also by mentoring them. Help them find their way. Even if it’s very exhausting because, of course, you are always trying to run your own life. But it is never enough to be only a personal success. You need to help your community too.

At Texas Institute of Letters, for example, a series of presidents starting with W.K. Stratton, Steve Davis, Carmen Tafolla, and I transformed the most prestigious literary organization in Texas to include more women and writers of color than ever before, to place them in positions of power as judges of our contests, and to award them our lifetime achievement award each year. All of these changes were long overdue, and we wanted to represent all of Texas, every community.

We inducted into our membership more Mexican-American, African-American, Asian-American, and LGBQ writers. Over the past few years, we have given the TIL’s lifetime achievement award to Sandra Cisneros, Pat Mora, Sarah Bird, John Rechy, and Naomi Shihab Nye. In my two-year term as president, we honored Benjamin Alire Saenz and Celeste Bedford Walker, the first African American to win the TIL’s highest award. We also held the TIL’s annual meeting in El Paso (twice), McAllen, Corpus Christi, and Houston, moving it beyond Dallas and Austin. So, change is possible, but it takes committed people and a lot of hard work to succeed.

So what advice would you give an up-and-coming Chicano writer?

The best piece of advice I would give you is to work your ass off. Work really hard and don’t be afraid to challenge norms and to go for ambitious goals. You have to read not just our literature but also beyond it, to improve your craft. To understand how to construct a story. You also have to reach out to other communities not necessarily Chicano/a to connect with other great writers who are similarly situated. You want to honor and read the best writers from all communities, not just a select few or the traditional few.

I would ask them whether they want to get an MFA. Nobody told me to get an MFA. I didn’t even know what an MFA was until after my first book. I learned craft on the fly. I did it by teaching myself, learning from others, and doing it. If I were younger, I would probably think about getting an MFA. But someone from the working class is not really taught about the possibilities of art. My father wanted me to make money and I did. But it took a long time and a lot of effort. I didn’t get a lot of sympathy from my parents because it wasn’t their milieu. A young Chicano/a writer needs somebody who can talk about how you make your way in the world of art, so that maybe they can get there quicker than some of us who did it on our own, on the fly. It’s important to keep your voice. It is important not to compromise your voice and to never forget the Mexican American community you come from.

Why do you get up in the morning every day?

I get up in the morning every day because I want to read and see our voices on the page. I want to see them in libraries. I want to be writing stories about our community as a proud Chicano but also as a writer who has expertly crafted stories so that everybody will appreciate a different perspective. I want to show others that we have the ability to tell complex, innovative, even shockingly revolutionary stories that open people’s eyes. I want to be an expert in the craft and to try different things but also never to leave the concerns of my community behind. I had my abuelita in my head every day even when I learned about Aristotle and even when I learned about craft issues in writing. Today I try to translate her concerns and my parents’ concerns and the values I learned from them into stories accessible to everyone. I am always ambitious but also uncompromising.

What is next for Sergio Troncoso?

Well, I hope maybe to get a stiff drink after this interview. I finished a memoir of essays about a poor Chicano starting in El Paso and then going to Harvard and Yale to become a writer. The memoir in essays explains how I went from Ysleta to the Ivy League, to recreate as much as I possibly could the transformations of my mind and also the struggles I faced to stay true to my community. I fought back at Harvard because I did not want to fail, I fought to understand how to write a great research paper, and I fought not to lose who I was, a Chicano from the border. I also learned so much about Mexican history. I had to go to Harvard to study Mexican history because in Texas they don’t teach you anything about Mexican history. I took advantage when I was at Harvard to study with professors like John Womack. For me, this memoir is really about coming home in a way and trying to tell people what happened to me. These are the lessons I learned, the failures I overcame, even the scandals I survived. Many of the topics in the memoir of essays I’ve never written about, this painful, haphazard, tumultuous transformation that happened to a poor Mexican American at Harvard and Yale.

Sergio Troncoso is the author of eight books, most recently Nobody’s Pilgrims, which won the Gold Medal for Best Novel- Adventure or Drama in English from the International Latino Book Awards. He also wrote A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son, which Luis Alberto Urrea called “a world-class collection.” Troncoso edited Nepantla Familias: An Anthology of Mexican American Literature on Families in between Worlds, which received a starred review from Kirkus Reviews. A Fulbright scholar, Troncoso is past president of the Texas Institute of Letters. He has been teaching at the Yale Writers’ Workshop since 2013. His work has appeared in the Yale Review, New Letters, Other Voices, Houston Chronicle, Texas Highways, Michigan Quarterly Review, and Texas Monthly.

Rey M. Rodríguez is a writer, advocate, and attorney who lives in Pasadena, California. He is currently working on a novel set in Mexico City and a non-fiction history of a prominent nonprofit in East LA. He has attended the Yale Writers’ Workshop multiple times and Palabras de Pueblo workshop once. He also participates in a selective Story Studio Novel in a Year Program. He recently was accepted into the Institute for American Indian Arts’ MFA Program in creative writing. This fall his poetry will be published in Huizache and you can find his other book reviews at La Bloga, the world’s longest-established Chicana-Chicano, Latina-Latino literary blog, Charter House, IAIA’s journal, and Los Angeles Review of Books.