REVIEW OF “LONG EXPOSURE”

By Loisa Fenichell

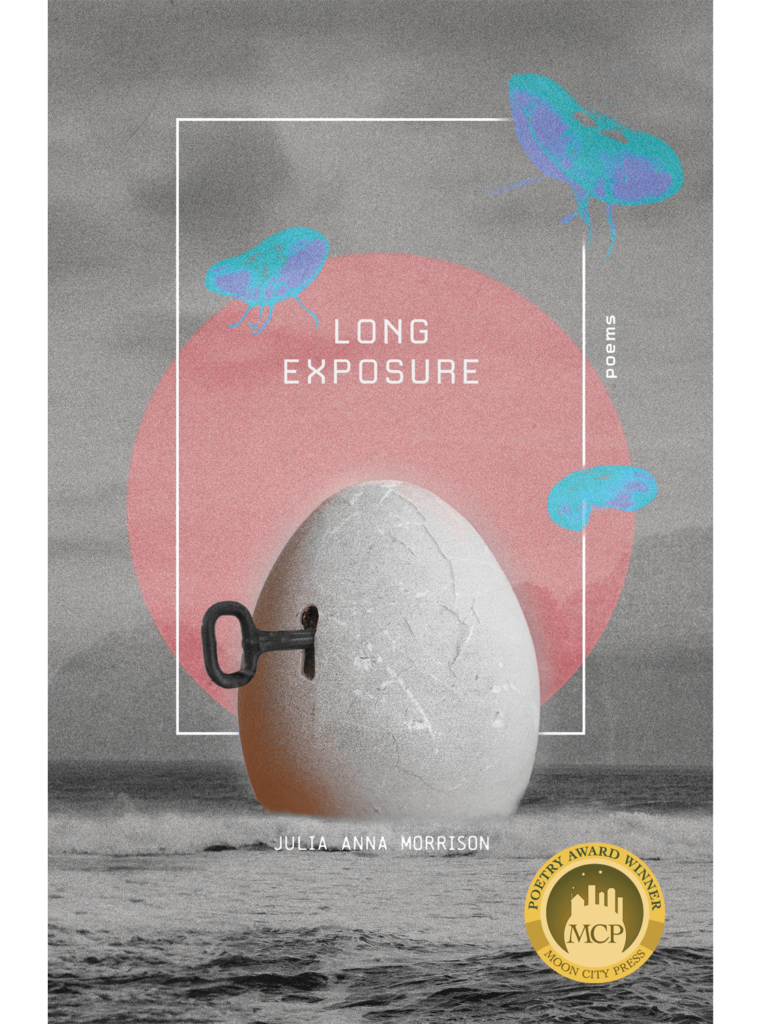

Long Exposure. Julia Anna Morrison. Moon City Press, 2023. $14.95

Grief and the Moon: A Review of Julia Anna Morrison’s Long Exposure

“The moon is the only model I have for motherhood,” Julia Anna Morrison writes in her award-winning debut poetry collection Long Exposure, in which Morrison adopts an older theme—the moon as a matrilineal symbol—and explores it through poems that are at once exceedingly authentic and vulnerable, and bolstered by more surreal images, to make this traditional theme her own. Long Exposure, in part due to its marriage of dreamlike imagery and more forthright, emotionally crisp confession is, above all else, visionary, a collection that does what so many others aim to do: deeply notices the dualities that play out in both poetry and in life, thereby transforming poetry into a life all its own.

The collection is split into three sections—“Fertile Window,” “Montage of a Drowning,” and “Rough Cut of Snow”—a fitting and precise number because the collection consists of three narratives that, while on the one hand are distinct, simultaneously bleed into one another to create an intricately woven braid: wifehood, sisterhood, and motherhood. What ties these narratives together is grief—grief of a husband lost through divorce, grief of a brother lost through death, and, finally, grief of what it means to be a woman prior to motherhood. What renders this last strand particularly compelling is that the speaker’s child—a son—is dually an emblem of grief and of reparation and restoration through the former two griefs.

For the speaker, this duality is precisely what makes motherhood so complex and is, in turn, what makes the theme of the moon as matrilineal sublimated and nuanced. “University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics,” one of the poems in the first section, explores the initial onset of motherhood by veering from the couplet:

One early evening I turn into a mother next

to some rocks and a pondinto the next,

When I am alone again, I look at my body:

a stretched-out image of a maiden,

a couplet that creates a striking vision of a postpartum state: the speaker, after “turn[ing] into a mother,” feels that she is no longer a “maiden”—defined as “a girl or young woman, especially an unmarried one”—but an “image,” a replica, of one and, not only that, but an image that is “stretched-out,” used, old. Yet this more unpleasant postpartum feeling is juxtaposed with the final couplet of a slightly later poem, “Owl.”

I peek at the baby and wish he’d start crying.

I could make him stop,

Here the speaker seems to have stepped into the role of a more “conventional” type of mother, one who knows she can provide comfort to “the baby”—she has the power to “make him stop.” Other lines, such as “My son was mine” in the poem “Sleep Anxiety”—a title that, in speaking to the anxieties of “sleep,” speaks to the anxieties of night, and all that comes with it, complicating the notion that the moon is strictly beautiful, it is also anxious, thus complicating the classic moon theme altogether—conveys the protectiveness the speaker feels for her child.

Despite this revelatory and transformative moment in “Owl,” motherhood remains fittingly multifaceted. Many of the other poems in Long Exposure navigate what it means to raise a child whose father is no longer the speaker’s husband, thereby rendering the child both an object of maternal love and an embodiment of grief, a reminder of somebody else who has been lost. Another poem in the first section, “At Squire Point,” articulates this more fully via lines like, “I should have never given birth. I feel a color / he left in my stomach when I am alone, shovel mark,” and, “At quiet hour I hear his papa and me talking before he was born. / Our childless voices, our love over the water… I could not give birth without losing.” These lines also perfectly encapsulate Morrison’s ability to tactfully straddle the border between surrealism (“I feel a color / he left in my stomach”) and realism (“I could not give birth without losing”).

While some poems, such as “At Squire Point,” excavate more specifically the loss of a husband and the birth of a child, other poems, especially in the second section, introduce the speaker’s brother into the fold, continuing to braid the three narratives together. “A Disease of the Mind,” for example, initially introduces the lost husband, “Asleep next to a man who does not love me any more than / he loves a river,” and then shifts, while using sleep as a connective tissue to “My little brother sleeps (does he sleep?) in a rehab center in / the Blue Ridge / Mountains. I pray for him to not take his own life.” Powerful poems successfully track the more natural movements and leaping of one’s inner-most thoughts while simultaneously managing an internal logic and organization, and this quality plays out throughout the collection in shifts such as this, in moving from the husband to the brother, using the image of sleep as a vehicle. Clear and poignant guilt is rendered in this poem, too:

When I hear his voice, I know his disease is my fault.

I could have taken it from him under a breath of silver

stars when he was seven.It barely fit into his hands it was so small

and oddly complicated, a nightmare.

This moment of clearly and vulnerably confessing to guilt, evident via the more explicit, “I know his disease is my fault,” still does not lose the magical and surreal qualities that traverse throughout the collection, due to the inclusion of the verdant and unusual, “breath of silver / stars.” Moments such as this convey how Morrison takes the very real and poignant emotion of guilt—wrapped up in the overall grief of the brother—and infuses it into poetry. In this way, the “real” life and the poetry are inseparable. As poet Andrew Zawacki writes in one of the collection’s blurbs, “These are human poems, the kind that bleed.”

Then there is the final poem, “Unfinished Ocean,” which perfectly fuses motherhood with the loss of the brother, and grapples with what it means for the speaker to love her recently birthed child while continuing to hold onto love for a relative who has died (the brother). At one point, the brother and the child seem to blur: “I used his name for you so I could sleep on his floor.” At the same time, the speaker wishes the child would heal the grief, though ultimately acknowledges that this is impossible. The poem—and the overall collection—ends with

When I die, I see him walking clearly into the unfinished ocean,

and even

though I love you, I go with him,

speaking, again, to the intricacies of motherhood, the way in which a mother can fiercely love her child while continuing to miss, and grieve, and want to be with somebody no longer alive—even if being with the dead means letting go of somebody else you love, somebody still alive. Motherhood and the moon are beautiful, enigmatic, and, above all else, complicated. The collection itself, in which the poems operate exquisitely both individually and fused together into an overall cohesive arc, reads the same.

Loisa Fenichell’s work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best New Poets, and has been featured or is forthcoming in Poetry Northwest, Washington Square Review, The Iowa Review, and elsewhere. Her collection, Wandering in All Directions Of This Earth, which was a 2021 and 2022 Tupelo Press Berkshire Prize finalist, was the winner of the 2022 Ghost Peach Press Prize, selected by Yale Younger Poets Prize winner Eduardo C. Corral, and published by Ghost Peach Press. She is currently a PhD student in English Literary Arts at University of Denver.