REVIEW OF RAISA TOLCHINSKY’S “GLASS JAW”

By Katherine James

Tolchinsky, Raisa. Glass Jaw. Persea Books, 2024. $17.00.

How Hard a Thing It Is to Say: On Feminist Revisioning, Vulnerability, and Touch in Raisa Tolchinsky’s Glass Jaw

There’s a strong tradition in contemporary poetry (well, in contemporary literature as a whole—thanks, Margaret Atwood) of feminist revisioning. Think of Louise Glück’s Meadowlands and Averno, Rita Dove’s Mother Love, Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette, and Lucille Clifton’s “eve thinking,” all of which draw an old story into the present, giving it a new—and profoundly personal—voice. Turning a classic tale on its head, Reginald Shepherd notes, allows the writer to “question its terms, bring out what it represses or excludes, give voice to those whom it silences, give presence to those it makes invisible.” Revisioning is a formal and political exercise: it hands the writer an old vessel, plus a flashlight to shine through the cracks.

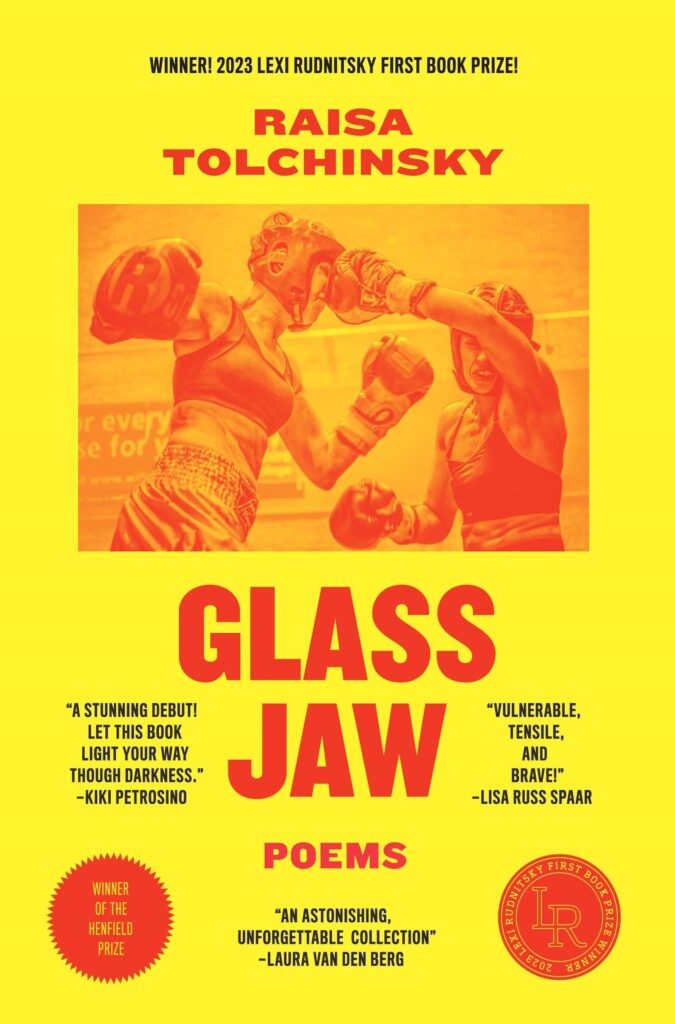

Winner of the 2023 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize, Glass Jaw, Raisa Tolchinsky’s electrifying and urgent debut, descends like Dante’s Inferno into a circuitous underworld: the female boxing ring. Through a series of poetic vignettes, the book chronicles the experiences of female fighters in New York City, their histories and interior lives, their physical and emotional wounds, what brings them to boxing. Tolchinsky reimagines Dante’s hellish rings as the windowless gym, its denizens her own ruminations. First told by a chorus of women, then through introspective eyes of a single boxer, Glass Jaw reveals a grim and glitzy world, where the “parting lips” and spotlight of the ring offer a place to grapple with womanhood, language, and above all, grief.

Tolchinsky herself trained as a boxer in the city for several years, and she writes with searing and effervescent honesty. Frank, embodied, and earnest, her speakers compare mascaras, do goblin squats, birth children. Pummel each other, then slip each other tampons. They skitter between bravado and shame, naivety and knowing—confident in their ability to hit and be hit, but always aware of the coaches, promotors, and spectators, men who define the rules of this underground world. “The audience wants whiplash, / wants a mouthpiece slick with blood…” one remarks. “Then, they want silence. / They want you crying in the corner like a still-life— / a vase, a bonnet, a little bird.” Why fight, and who is the fight for? As another fighter confesses:

…I hit her hard

because he said that’s how you win

and I hit her until I remembered

it was him who was afraid—

The male gaze here expands beyond the ring—it is historic, literary, and all-consuming. “How can a woman be decent, / sticking her head in a helmet, / denying the sex she was born with?” reads the epigraph from Juvenal’s Satire VI, a challenge the first section of the book works to overcome. Literally and figuratively: Tolchinsky expands this quote into several golden shovel-esque prose blocks, which in turn frame a chorus of boxer persona poems. “Call this ‘woman’s work’ because no one has the words for how it feels to be bloody in your mind,” she writes, even as she gives voice to these modern women in helmets.

Like the revisioning projects of Glück, Dove, and Notley, Glass Jaw combines the Dantean structure of “the ring below the ring” with a painterly determination to depict the material and emotional particularities of contemporary life. “[It was] the perfect architecture for what I was hoping to write,” Tolchinsky said in an interview with Persea, “especially since many of the places where I trained were actually underground, in basements.” While the book’s second half (“Here this Hollow Space”) uses Inferno’s 34 cantos to build the ladder down, Tolchinsky’s rich storytelling shimmers with a vernacular that fans of gurlesque—or anyone who grew up in the 90s watching Clueless and Thelma & Louise—will recognize as their own: a language of baby pink pantsuits, Vick’s, Tilda Swinton, Gatorade, and Tarot cards.

“Retellings and persona poems not only allow the writer to discover what utterances emerge in the dark, but they relish in all the shadowy details—things hidden, things forgotten, things unsaid,” Jennifer S. Cheng writes about her forays into revisioning. The dark, the forest: where many old tales begin. Where Inferno begins: Midway upon the journey of my life / I found myself within a forest dark / For the straightforward path had been lost. Like Dante’s narrator, the speaker of “Here This Hollow Space” is singular, a lone boxer plunging, quickly, into memory—a city of midnight shifts, subways, locker rooms, shadowboxes. “Now you are not a girl walking through the park / but a myth preparing for an ending,” Tolchinsky writes, and the poems begin to spiral, sometimes with slickness and sometimes shuddering, toward the previously unspoken core: the years the speaker spends in a relationship with an abusive and predatory coach.

Glass Jaw’s revisioning of Inferno makes us wonder: what is hell? A lesser poet might point directly to the patriarchal, violent world of the ring, but Tolchinsky, even as she critiques, remains a boxer, relentlessly searching for inconsistencies, vulnerabilities. She is more interested in moral complexity than blame. “I was good / at being good,” she confesses, “at saying please and thank you / until it blackened another’s cheek.” Her empathy excludes no one, even the coach, and her questions keep us pivoting:

Coach kept changing shape—

devil, monster, minotaur

with rotted horns

but sometimes

a weeping man, dark curls

spilling across my lap—

or was it me who changed him…

as I squinted my eyes

then handed over a paisley shirt?

In myth, transformation is sometimes punishment and sometimes a form of agency. Daphne changes into a laurel tree, Demeter into a mare. Self-imposed, it becomes protection, a shield, making unwanted touch impossible. But armor’s boundary is total—neither does it allow a healing touch. “In a rom-com we’d hatch a plan, take over / the gym and leave him with nothing,” the speaker remarks, after learning about all of the other women her coach has pursued. “The problem was, I was mesmerized / by my own routine…felt safe knowing where he was— / inside the day, not the tangle / of my mind.” The true devils here are isolation and silence.

If Dante descends through hell before ascending through purgatory into heaven, then Tolchinsky’s cantos, ordered in reverse, point back to the book’s beginning, with its cluster of female boxers, as a paradoxical paradise. A punch is also a touch, the word vulnerable derives from the Latin vulnus—a wound. These poems, even as they stand in the boxing ring, are full of other types of touch: mothers birth daughters with fingers curled into fists, a woman shows a girl how to throw an uppercut, two boxers kiss under the streetlights after a fight. In these poems, the hands that fight are the same as those that heal, that make “tinctures thick as honey for / my sparring partners.” A “glass jaw”—someone easily knocked out by a blow to the chin—is fragile, but I’m struck by the phrase’s toughness, the solid symmetry of these two single syllables. Month after month, millennia after millennia, she reminds us, women’s “bodies emptied / without breaking.”

Even as her speakers grapple with violence, competition, and isolation under the patriarchal spotlight, Tolchinsky, through masterful craft and storytelling, weaves a web of feminine solidarity, deftly navigating the paradoxical connection of each punch. Hers is a poetics of profound intimacy and fierce joy. As one fighter confesses: “I felt like I could love / her like a person / instead of a fighter / in between rounds.”

Katherine James is a writer and maker based in rural Virginia. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Virginia, and her work has appeared in or is forthcoming from Architectural Digest, Fifty Grande, The Denver Quarterly, and The Citron Review.