The Magic of Renaming in, “Spells of My Name,” by I.S. Jones

Jones, I.S., Spells of My Name. Newfound Press, November 2021

Review by Taylor Byas

The familiar saying from Audre Lorde goes, “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” but I would argue that I.S. Jones’ debut chapbook, Spells of My Name, contends with Lorde. In this collection, Jones faces off with the America, both its violent history and its enduring obsession with conquering, naming, and categorizing everything within its scope. Everything this country uses against the speaker—her Blackness, her womanhood, her queerness—Jones fashions into weapons of subversion.

One of Jones’ most striking rebellions is her poetic refusal to assimilate, the undoing of Americanization. In her “Interview with the American / Nigerian” series, the title itself resists the usual coupling we see in the title of “African American.” Grammatically, even the order of “African American” casts the word “African” as an adjective, a descriptor of the type of American one may be (because one is American before anything else). And yet Jones insists on the separation, writes in the first “Interview with the American / Nigerian” poem, “The hunter levels his gun to the fawn’s head. I close my eyes. Fold / my first name under my tongue. Living before was deceptive: an / American with an Edo girl’s face. For years, I told no one I was as Nigerian / as I am American” (6). Here we see the speaker actively splitting before our eyes: first as human/fawn, then as American/Edo, and finally as Nigerian/American. The poem’s erasure form also hints as an intentional self-fashioning on both the speaker and Jones’ behalf—the decision of what remains scene and what gets blacked out is simultaneously a decision of how one is choosing to present the self. This partitioning, these “fragmented pieces of the Singular” are necessary for the speaker’s own survival in America (7).

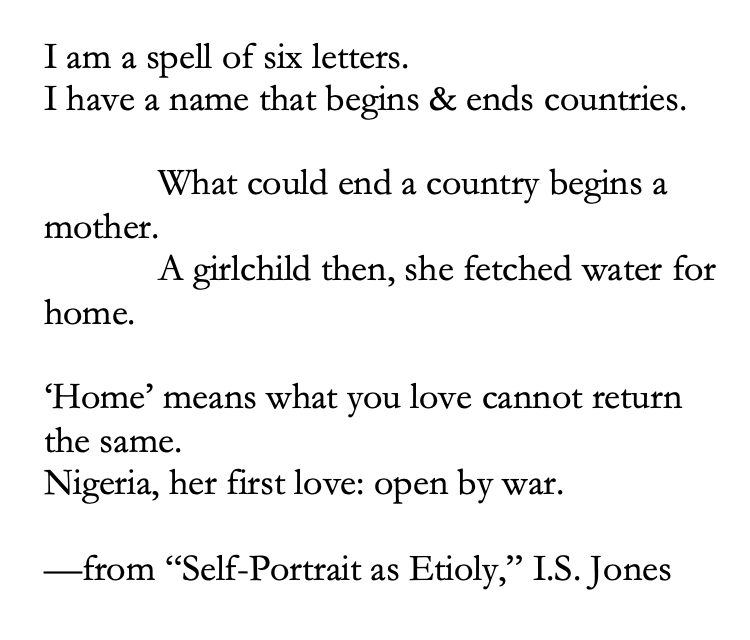

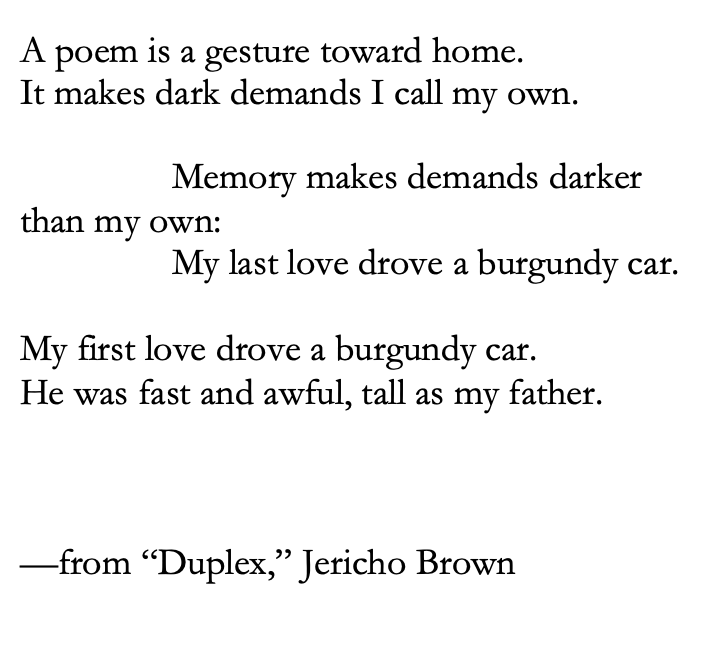

Those fragmented selves explode outward across the book, reappearing as a series of “Self-Portrait” poems that feel distinctly different from one another. In the first iteration “Self-Portrait as Etioly,” Jones utilizes Jericho Brown’s duplex form and contains obvious echoes of Brown’s original “Duplex” poem, which can be seen by comparing the first three couplets of each poem:

If Brown’s “Duplex” is first a gesture towards home, and then an exploration of how his own parents fit into the landscape, the Jones self-portrait follows in Brown’s footsteps as the speaker considers the version of her closest to home. The second self-portrait poem, “Self-Portrait as Itiola,” is clearly more Americanized. The poem is littered with American and contemporary buzz words such as “capitalism,” “Buzzfeed,” and “Twitter.” The version of the speaker in this poem laments, “every day i look out my window / like a woman who missed out on her life / being everyone’s something else,” which feels like a direct call back to Etioly, a version of the self before assimilation (19). The final poem in this series, “Self-Portrait as Tiona,” is arguably the speaker’s most powerful version of the self, as her knowledge of societal power dynamics allows her to sabotage them. Even the voice crackles with dominance as the speaker taunts her lover; “I am cruel, but I didn’t rewrite a thing, babe. / You’re not a monster, just a man” (25). The subversion of power is both one of this chapbook’s largest missions, and one of its greatest successes.

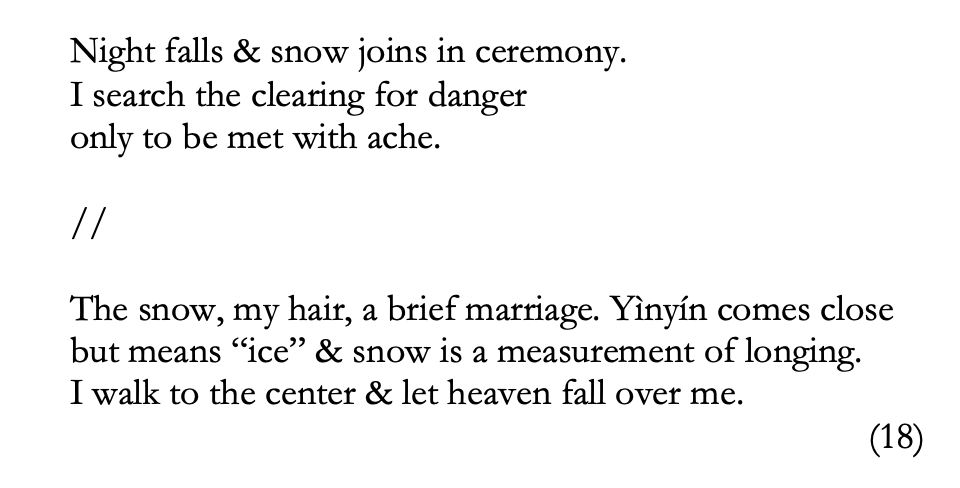

The collection is replete with dualities, and extremely aware of the power dynamics that often accompany them. Jones renews and intentionally inverts the historical literary symbolism of black vs. white again and again. With darkness typically aligning with evil and light being associated with good, Jones recasts the combination as the helpless black fawn and the violent faceless hunter, the pure black night and the heavy white snow that erases all that it covers. On the one hand, this signifies racial differences, the speaker’s blackness propped up against and compared to America’s whiteness. In “What We Agreed to Call ‘Snow’ in Yorùbá,” Jones beautifully captures this contrast:

From the poem’s opening tercet to its closing one, a transformation takes place, a substitution even. At the beginning, the night and the snow are cast as mere opposites, the snow “a landscape of loneliness” directly parallel to the sky (18). But by the end of the poem, the speaker’s hair replaces the night. This substitution charges the relationship between black and white with power, and it is the snow that becomes the aggressor. The poem’s final line feels deceptively welcoming—“I walk to the center & let heaven fall over me” serves as a euphemism for white America’s erasure of the speaker’s blackness.

One the other hand, Jones interrogates the power dynamics at the intersection of both race and gender, how the white patriarchy predisposes Black women to precarious relationships with men, their first offenders often their own fathers. In “My Therapist Asks, ‘Is the Hunter in your Dreams your Father?’,” the speaker confirms that the hunter haunting her dreams is her father, says “The hunter cocks back his gun. Calls it fathering…//…When the moment came, I didn’t hesitate to walk / into my father’s eye” (32). But let us not forget that the hunter remains faceless throughout the chapbook. The speaker’s father was her first hunter, the first in a long bloodline of hunters the speaker would encounter throughout her life and in her relationships with other men. If “the dark space [her] father left behind is a father [and the] dark space his father left behind is a father,” then this must mean that men inherit their wounds and pass them down like heirlooms. In America, men are only taught that they are hunters, and everything else is theirs for the taking.

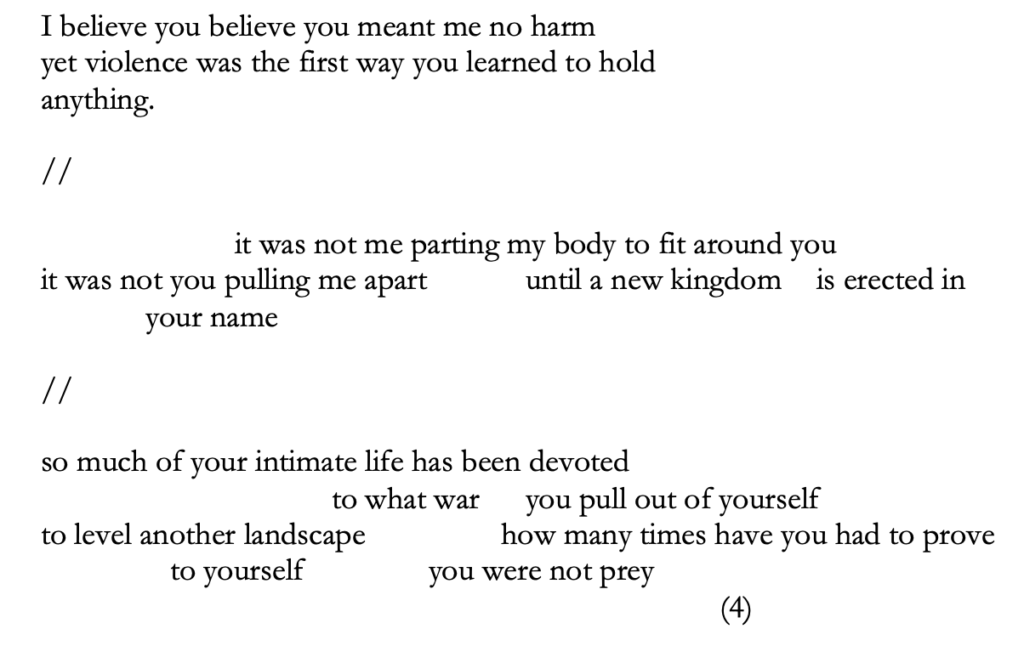

Jones investigates how men’s problematic education leaves no safe spaces for Black women, not even within the realm of intimacy. The collection’s opening poem, “A Field, Any Field,” interprets the bedroom as another battlefield, the Black female body another war for men to win. The poem moves from a more traditional lineated form before fracturing as it progresses:

Jones illustrates that the language of sex is colonized by violence, and the language of violence is simultaneously colonized by male sexual desire. A kingdom is “erected,” the body is “parted,” the man “levels” a woman in bed. In another poem, “Queen American,” Jones opens with “ I have sex with men but make love to women,” drawing a clear distinction between sex with men and queer sex with other women. The sexual encounter the speaker has with the man in “A Field, Any Field” is a constant grappling of power, the man trying to dominate and the speaker wishing they could “both to one another be prey” (5). With other women, the likelihood of an even playing field is much higher—in the absence of male violence, love and tenderness have permission to bloom. So the question remains; if this country’s violent and male-dominated history troubles our most sacred and private spaces, where does the Black queer woman find safety?

Jones would argue that the Black queer woman must wield her own magic, must name and rename that which threatens and oppresses her. And through the spells of naming, the Black queer woman can rewrite her history, rewrite America’s repetitive ending.

I.S. Jones is an American / Nigerian poet, essayist, and music journalist. She is a Graduate Fellow with The Watering Hole and holds fellowships from Callaloo, BOAAT Writer’s Retreat, and Brooklyn Poets. I.S. hosts a month-long, online poetry workshop every April called The Singing Bullet. She is the co-editor of The Young African Poets Anthology: The Fire That Is Dreamed Of (Agbowó, 2020) and served as the inaugural nonfiction guest editor for Lolwe. She is an Editor at 20.35 Africa: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry, freelanced for Complex, Revolt TV, NBC News THINK, and elsewhere. Her works have appeared or is forthcoming in Guernica, Washington Square Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Hobart, LA Review of Books, The Rumpus, The Offing, Transition, Shade Literary Arts, Blood Orange Review, Honey Literary and elsewhere. Her poem “Vanity” was chosen by Khadijah Queen as a finalist for the 2020 Sublingua Prize for Poetry. She received her MFA in Poetry at UW–Madison where she was the inaugural 2019–2020 Kemper K. Knapp University Fellowship and is the 2021-2022 Hoffman Hall Emerging Artist Fellowship recipient. She is the Director of the Watershed Reading Series with Art + Literature Laboratory, a community-driven contemporary arts center in Madison, Wisconsin. Her chapbook Spells of My Name (2021) is out with Newfound.

Taylor Byas is a Black Chicago native currently living in Cincinnati, Ohio. She is the 1st place winner of the 2020 Poetry Super Highway, the 2020 Frontier Poetry Award for New Poets Contests, and the 2021 Adrienne Rich Poetry Prize. She is the author of the chapbook Bloodwarm from Variant Lit, Shutter, forthcoming from Madhouse Press, and her debut full-length, I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times, forthcoming from Soft Skull Press in Spring of 2023. She is represented by Rena Rossner of the Deborah Harris Agency.