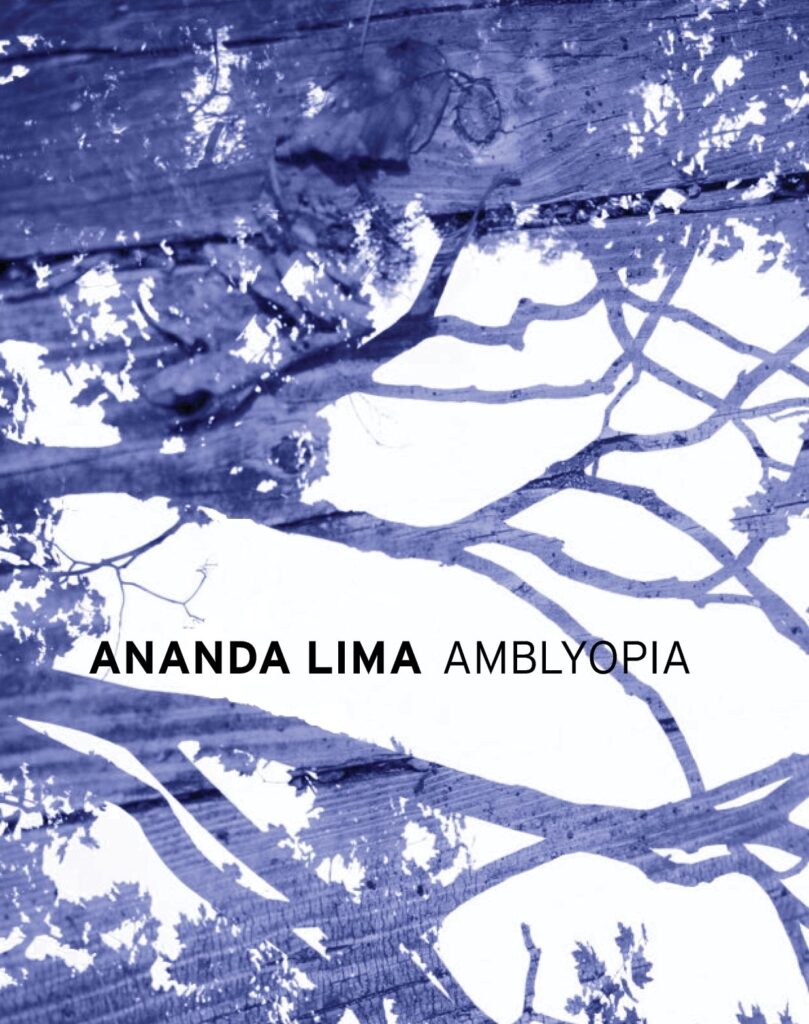

Vision, Memory, and Forgiveness: A Review of Ananda Lima’s Micro-Chapbook “Amblyopia”

By Shari Astalos

Amblyopia, Ananda Lima, Bull City Press, 2020, 20 pp. $3.99

Amblyopia, a neurological condition that appears in early childhood, occurs when pathways between the brain and the eye are not stimulated. This leads to the brain favoring one eye, along with decreased vision in the other. Ananda Lima’s micro-chapbook, Amblyopia, embodies this condition, with the soft blurry edges of memories, of inheritance, and of the way one’s absorption of the world is both affected and interpreted.

This chapbook engulfs the intersections of motherhood, illness, blame, and forgiveness. Lima writes not only about what a mother might share with her child, but also what she might keep separate, along with the aspects of our behaviors and traits that can be unlearned or healed. Throughout these poems, Lima’s speaker references her childhood and her history of amblyopia. She notes the ways in which her vision was never treated, and how she wishes for a different outcome for her son — she hopes that he will overcome what she did not. The speaker shares the physical aspects of this particular ocular condition with her son, but she attempts to keep him from sharing in her version of impaired vision.

Lima writes this chapbook, as she does in many of her other works, partially in Portuguese. In Amblyopia, the speaker introduces Portuguese in order to demonstrate the ways in which her son’s eye condition is reflected in her life, as well as to imprint parts of her childhood experience onto him.

For example, in the titular poem, “Amblyopia,” Lima translates certain phrases from English into Portuguese, which she intentionally fades, using differing shades of gray. Lima’s use of faded Portuguese, while keeping all of the English words clear, appears to mimic both suppressed vision and a suppressed part of the speaker’s self:

“I close my right eye meu olho direito // and see everything tudo / que // my mother and my father meu pais / no meu país // didn’t // know // to do / tudo // then / que fazer? // e hoje, minha vista cansada // not a matter of laziness // the doctor says // it’s more / mais mas // of a suppression // a lack / falta // of focus / foco“

In the poem’s opening, the speaker references her own childhood and the ways in which her amblyopia was not treated. She states that she closes her right eye and as a result, sees everything that her parents did not know how to do, as well as the things that she must do for her son in order to treat his condition. The words written in Portuguese appear initially in a clear black font, but then begin to fade to a lighter, more out of focus gray. Some of the Portuguese words correspond to their English meanings, while others do not. For example, after “my mother and my father,” Lima writes “meu pais/no meu país,” which translates to “my country/not my country.” There is also one stand-alone phrase in faded Portuguese which does not correspond to any English: “e hoje, minha vista cansada”, which translates to “and today, my tired eyes” or, “and today, my weary view.” The specific words that Lima chooses to translate from English to Portuguese: falta (a lack), foco (focus), heighten the confusion and decreased visibility that comes with amblyopia.

“A Orelha E O Ouvido” is another poem that emphasizes the role language plays within the speaker’s life, especially as a mother:

“he shows me the difference between years / and ears in vain I say that we have two / words for it in my language (mine and his / too I correct myself)”

Through the exact rhyme of “years” and “ears,” Lima mimics the mishearing or misunderstanding that may take place between speakers who share different first languages or different relationships to language, even if they are related as closely as parent and child. In this way, Lima returns to the boundaries between mother and child—what a mother can give her child and what she cannot, or how children can break away from their mothers and come into their own identities. She also speaks to how a mother’s experience of home can sometimes never reach her child.

By purposely choosing the words “years” and “ears,” and by separating them with a specific use of enjambments, the reader feels a sense of marked time and the importance of the way one perceives the world around them.

In “Amblyopia,” the title piece, Lima’s speaker states:

“I learned to delight in gifts of myopia… / so cute how I never know where I am… / my condition a pastel-tinged party trick / watch me get lost in my vapor watch me / get by until it thickens into clouds / condenses down into my son’s eyes.”

Lima’s words speak volumes about motherhood, in how her condition is no longer a harmless aspect of her being, or a cute “party trick,” but is instead a point of guilt, in that this aspect of herself that she found innocent is now a hindrance to her son. This is especially clear in the line, “condenses down into my son’s eyes,” which displays how this so-called “pastel-tinged party trick” then has generational consequences. Here, Lima’s speaker reflects on how mothers can feel responsible even for those circumstances of their children’s lives over which they have no control.

Lima returns to the feelings of blame and forgiveness, playing on the relationship of mother and child in “Self as Daughter”:

“Not your fault / I tell her in English / my grown woman child / sitting by the window / in the brown carpeted / optometrist office / so difficult to apologize / but I do / and I hold her hand / and she holds her boy’s”

The speaker’s apology to herself comes in English, as she explores the boundaries of language and forgiveness. Her characterization of herself as “my grown woman child” and “self as daughter,” along with the action of holding her own hand to forgive herself exhibits this exploration of boundaries. The speaker temporarily shifts her role to fully scrutinize how the forgiveness of oneself works.

In her stunning prose poem, “Zoológico, Circa 1982,” Lima’s speaker plumbs the depths of her memory to recall a blurry, hot bright afternoon at the zoo as a young girl. The language is vivid and hazy, like memory itself, and like the act of seeing is for the speaker and her son:

“We were little and we wore white we squinted at all that light we / were hungry we were given pink candied popcorn we licked our / sugared fingers the air hot and heavy with água doce everything / infused in sunlight in a tinge of purple and I don’t know if what / I recall is that day a blend of different days or a photograph (…) /…we look at the photographs of me as a child now I find her beautiful she looks / like my son and I like my mother.”

The lack of punctuation in this poem, along with the imagery of heavy, colored light, provides a heightened feeling of blurriness and confusion, mirroring the murkiness of memory itself. Within the speaker’s final words, especially “she looks / like my son and I like my mother,” there again we find a return to a feeling of inheritance and forgiveness. Here, the speaker locates an echo of beauty throughout the generations—in herself and her mother and her son. The speaker locates beauty in the form of acceptance, and she may be finding beauty in the fact that she can see her likeness in both her own mother and her son.Amblyopia probes the way in which the speaker views her own memories as well as the present moments she creates with her child, in light of their shared amblyopia. The poems address the way the speaker’s vision and viewpoint affect her sense of self. Lima’s book speaks to the intertwining of vision and memory—the way individuals store and ferret away those moments that they see and experience, and how the memories collect dust or sharpen over time.

Ananda Lima is the author of Mother/land (Black Lawrence Press, 2021), winner of the Hudson Prize, shortlisted for the Chicago Review of Books Chriby Awards. She is also the author of four chapbooks: Vigil (Get Fresh Books, 2021), Tropicália (Newfound, 2021, winner of the Newfound Prose Prize), Amblyopia (Bull City Press, 2020), and Translation (Paper Nautilus, 2019, winner of the Vella Chapbook Prize). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, Colorado Review, Poet Lore, Poetry Northwest, Pleiades, and elsewhere. She has served as the poetry judge for the AWP Kurt Brown Prize, as staff at the Sewanee Writers Conference, and as a mentor at the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Immigrant Artist Program. She has been awarded the inaugural Work-In-Progress Fellowship by Latinx-in-Publishing, sponsored by Macmillan Publishers, for her fiction manuscript-in-progress. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark.

Shari Astalos is a writer from New Jersey. She holds degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Miami School of Law. She is currently an MFA candidate in the creative writing program at Rutgers-Newark, where she is also a lecturer in the English Department.