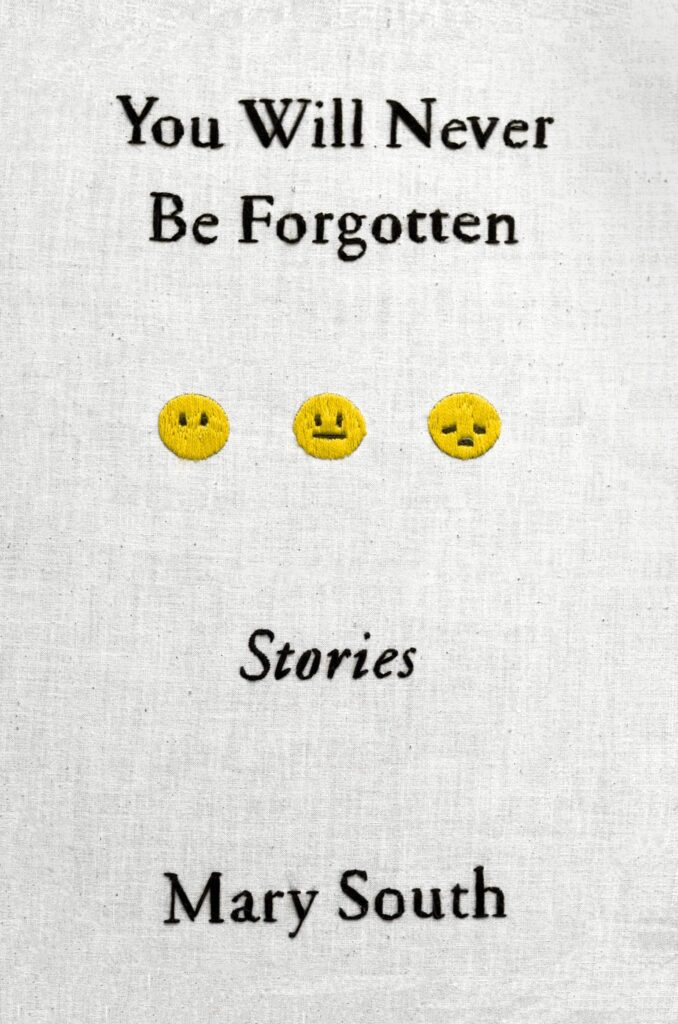

A Review of Mary South’s, “You Will Never be Forgotten”

by Vince Granata

You Will Never be Forgotten, Mary South. FSG Originals, 2020. 265 pages. $15.00

When a mother loses her nine year-old daughter, she discovers a way to circumvent grief. She plans a “rebirth,” a subsequent child, a duplicate for the daughter she’d lost. “If our baby was returning to us, there was nothing to grieve,” she explains. The mother painstakingly reenacts her first daughter’s life with her genetic copy. A first kiss, the death of a pet, and birthday parties are all scripted and choreographed to occur as they had before. Through control of this duplicate daughter, the mother tries to resurrect the child she lost.

Grief is a feral thing in Mary South’s stunning debut story collection You Will Never Be Forgotten. The wounded mother in South’s “Not Setsuko,” is one of many characters who look for a balm for uncontrollable feelings—grief, rage, desperation. Across ten stories, South inhabits people grasping to stay tethered to their ghosts. Loss and trauma are not easily bandaged. Wounds stay open, leave caverns to fill and fill.

Trauma infantilizes a group of men, leaves them groveling for taboo maternal intimacy while they bicker and fight, propping up each other’s sadness at a hostel on the Turkish coast.

A celebrated architect from a fractured family superimposes her daughter’s craniofacial microsomia onto designs for buildings, plans that mirror her form.

Loss compounds as a relator for the houses of the recently deceased mourns his wife. “A memory is altered each time it is recollected,” South’s protagonist claims, “[w]henever I long for my wife I lose her more and more.” In his grief he recognizes the totality of his haunting.

“What can be more ghostly than missing someone so intensely that you can no longer remember her as she was?”

I’ve read a lot about grief. I look for characters like South’s characters, people who struggle to bend their worlds into shape after trauma and loss, who clutch totems of memory for people who are gone.

I used to read about grief to try to recognize myself, make sense of the ways I’d tried to hold onto my mother after I lost her suddenly. Then, I read books written like manuals, ways to measure progress in Kübler-Ross stages, daily meditations that trained focus forward to the next day, then the next, then the next.

But nothing about my life felt linear. I clung to a voicemail from my mother, thirty-three seconds of her voice I’d saved on my phone.

I almost lost it once. Months after she died, I fell into a river. My phone was in my pocket.

I remember standing in a Verizon store—still soaking wet—while a man in a polo shirt told me to enter my name into a tablet.

“Someone will take care of you,” he said, looking away from where I dripped on the gray carpet.

When an employee called my name, I thrust my phone forward, clutched its dark husk.

“My phone died,” I said. Then, near tears, “is my voicemail gone?”

I looked at my thumb, still pressing the round power button, red flaring beneath my nail.

I did a lot that surprised me after I lost my mother, acts more irrational than standing in a puddle in a Verizon Store. I still wonder about this person, who I’d become after trauma and loss.

“If you’re reading this page, chances are you’ve recently heard that you need to have a craniotomy. Try not to worry.” Through a hospital website’s frequently asked questions page, South inhabits the voice of a neurosurgeon addressing patient concerns. Though the document, ostensibly, aims to placate fears, South’s surgeon offers direct—often lyrical, often wryly funny—descriptions of what appears within our skulls. “The blush of living brain has been described as resembling the inside of a conch shell or a crumbling marble quarry. To me, it’s like the revelation of brine and meat after shucking an oyster.” As the questions progress, the reader begins to see the neurosurgeon herself peeled back, observes the traumatic loss that has lead her to transform this online document into an extension of her own crisis. “Now, I wonder: When I am resecting a brain to prevent seizures, for example, what am I attempting to fix?”

Many of South’s stories look at how technology becomes a vehicle for complex feelings after loss or trauma. Just as her neurosurgeon twists a webpage into an accounting of her own grief, other characters use—and often abuse—technology as means of escape or control. Masterfully, South writes from the collective perspective of a Sci-fi show’s rabid fan base, tracing how the group worships, objectifies, and reviles the series’ lead actress in a dizzying cycle of online obsession and toxic vitriol.

In the title story, a woman tracks her rapist through his conspicuous footprint online. An employee of “the world’s biggest search engine,” South’s protagonist is adept at combing the Internet, her job, sanitizing the web of pornography and gore. While she first monitors her rapist virtually, eventually she finds a way to seep into his real life. As she watches him in the aftermath of her sexual assault—unscathed, thriving—South’s character loses the tether to her own life. Trauma does its work to transform.

While technology features prominently in many of these stories, the stories are haunting for reasons beyond South’s deft treatment of tech as a complicated crutch for unresolved pain. These stories are unforgettable because South shows how fully grief, rage, and hopelessness can alter recognizable humans into characters grasping for any means to quiet roiling pain.

In the midst of grief, one of South’s characters receives advice from a store clerk on how to contend with moments of psychic pain. “Take one ordinary action—pouring a glass of water, or peeling an orange—and slow it down, slow it way down until it becomes almost unbearably beautiful, then recite to [your]self ‘I am alive.’” South renders struggle in precisely this way, unbearably beautiful stories of ordinary humans in extraordinary pain, the ways they fight to stay alive.

Vince Granata received his BA in history from Yale University and his MFA in creative writing from American University. He has received fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Brush Creek Foundation for the Arts, the I-Park Foundation, and the Ucross Foundation, and residencies from PLAYA and MacDowell. His work has appeared in The Massachusetts Review, The Chattahoochee Review, and Fourth Genre, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and listed as Notable in Best American Essays 2018.

Mary South is a graduate of Northwestern University and the MFA program in fiction at Columbia University. For many years, she has worked with Diane Williams as an editor at the literary journal NOON. She is also the recipient of a Bread Loaf work-study fellowship and residences at VCCA and Jentel. Her writing has appeared in American Short Fiction, The Baffler, The Believer, BOMB, The Collagist, Conjunctions, Electric Literature, Guernica, LARB Quarterly, The New Yorker, NOON, The Offing, The White Review, and Words Without Borders. Maile Meloy awarded her story “Not Setsuko” an honorable mention in the Zoetrope: All Story fiction contest.