A Celebration of Franz Wright, Day 5

Gretchen Marquette

EVERY SYMPHONY IS A SUICIDE POSTPONED

– after Franz Wright

If you have an exit wound, you can be sure what struck you has passed clean through. If you’ve been hit once, you’re always being hit, but whatever is hurting you is always leaving you too. At some point, you’ll sit up and ask for water. Out of the woods, they say, but what prey animal wants a clearing? As we all know, you can never go home again. Change inserts itself into every space, as when they cut down the elm in front of my house. I used to lie in my second story bedroom and observe its branches, thick as trunks of lesser trees. One of the branches was warped, and looked like a horse’s back and neck. During all seasons, winter notwithstanding, the horse had a mane of leaves. In some ways, I was new to the world again, and I suffered. But it comforted me to watch the tree horse run in the wind. It never arrived, just ran for the sake of it, which is what I assumed I was doing. Nothing happens until something moves, but nothing holds still. Maybe that’s the point. But what’s moving here, at the museum, in the still life, its permanent image of fecundity? What’s hidden from us–the way each orange in the bowl has a side flattened by the gentle pressure of its kin? What should you do if I fall asleep? There were long hours in those first months, spent ruminating over mundane aspects of death, such as blood’s viscosity, given a specific temperature and duration of time, thickness that could impede one’s heart’s beating. I thought about these things, but also took multivitamins, and went to the chiropractor. Sometimes words were ineffective. When I was little, I learned my language twice. The second version is the one I speak to you. The first version is the one I speak to myself, wherein the person in the house beside mine is my neckstornaybur. Wherein I fear the blue, fanged mizturwoolf. Wherein my mother plants Mary Golds. My first language was not immune to grief, but neither was it made from it. This is how I spent three years of my life: counting pills of different sizes and shapes into a single exit bottle that wouldn’t let me vomit or suffer, and also finding myself overcome by the sight of my wet footprints on the bathmat. Why are you here? Two years after his mother’s death, my friend is still panicked. Our conversation rapidly veers in her direction as if we’re in a raft on a river of sorrow. Where is she? I mean…where did she go? his voice rises, he throws his hands up in the air. These are a child’s questions for one moment only, and then foul unanswerables. When my dog died, I knew she was as far from me as was possible to go, and still she was more mine than the birds in the park. I held her when they injected the poison. Her breath was sharp, and then it stopped. The vet, a gentle woman younger than me said, “I don’t hear anything,” and placed her stethoscope back around her neck. I let myself look back, once, at her body lying on the green blanket on the floor. Every night I hold the dog who is still living. Every night I say, please stay as long as you can. Praying to an unavailable god means saying, I look for you most in the evening, when it’s getting late, when the sun ratchets away. There must be something left in my animal body that fears the dark that has everything to do with being swallowed whole. There must be something to be said for how we’ve learned to burn the fat of other animals to make our light. The world is a big place, but there are few places to set love down and darkness is a problem to be solved. When I turn out the lights too quickly on the way to bed, my old dog, nearly blind, freezes where she is and waits for me to come back for her. Earlier tonight I thought her eyes look milky like a spider’s, and then I felt so sad, I thought, that’s not true, she’s the most beautiful thing I have ever seen, and I rubbed her ears between my thumbs and forefingers and cried a little too. This is a world where nearly everything hurts, despite it being such a big place. One has to consent to that. I spent three winters watching the tree horse thrashing, naked in the wind. Before they took it away, I tried to take a photo of it, but as a static thing it lost all grace.

Ellen Kombiyil

ELEGY WITH PREMONITION & TENTACLES

And words should not fade or blur

But remain static as photographs pressed in plastic,

Coated with fingerprints. You are like that

Dogwood demanding shade over uneven

Earth, dogwood lightning-struck &

Fissured one final night, then

Gorged by termites. The still living tree,

Harmed & keening, will be chopped

Into fireplace-sized logs, split

Jagged for better burning. All gone

Kitchen shade of the same house over which it was

Looming. That is you/not you

Lying supine in your bed of brown,

Mysterious place for

Naming yourself, not spoken

Out loud. Now/not now in new sky, spreading,

Precise gleam of wild light.

Quiet memory is like that burning:

Respite from high ceilings, echoing feet,

Rest In Peace a construct to help yourself

Sleep. Too big to hold you: collapsing absence of steps,

Tunnel of creaky structures remind you to

Unforget. Go now, dive in deep water,

Venture into murky depths.

What creatures will you write of then? You shall name them, tally

(X) number of tentacles or fins, measure fluttering hearts

Yearning for breath, yes, patterned like ocean currents counting

Zero to ten, the pushing out & the sucking in.

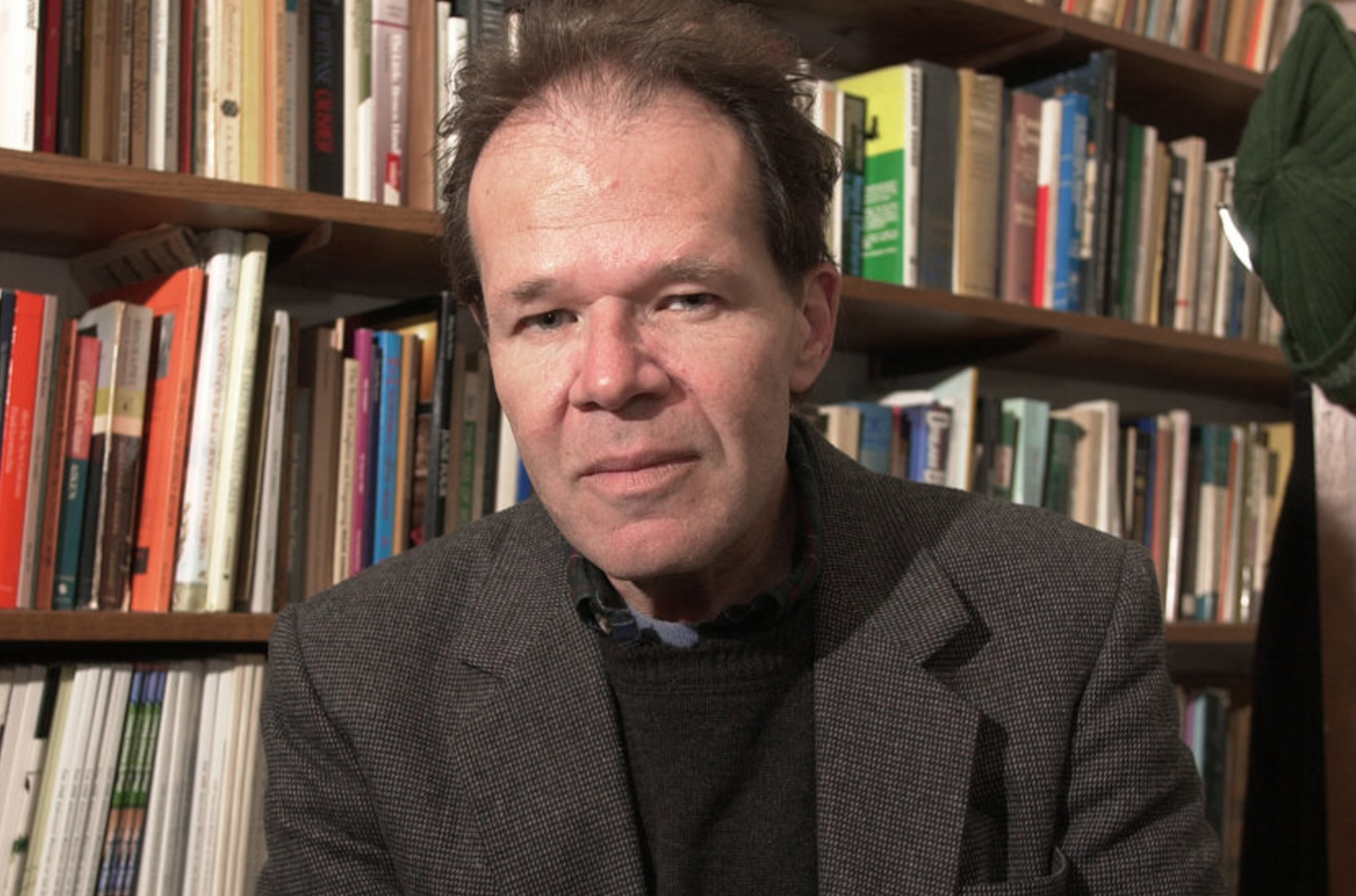

Franz Wright

NIGHT WINDS

Nude footprints at evening, in August, commingling and rapidly vanishing toward me across the scarlet water, noir. And from moment to moment continuing to darken toward the boundary of night and last light, deep sleep and a dawning awareness of being asleep… From lake to land they step with no more effort than it takes to get off a horizontal escalator. Each evening I waited in the blond shade of that ancient yellow willow, swaying and sieving, in the faint stench of drowned fish, pale bellies swollen to the moon; I waited in the moon with one star shining where it wasn’t, masterful masse of starlight curving around the fields of lunar gravity. They crowded around me, each in turn reading my face with her cool hands, before hurrying on. All except for one who stayed behind and stood facing me suddenly and gazing past my shoulder as though through the sky. So much younger than I yet she was here before I ever breathed and will be here when I am not, this ghost of future dusks, this scarlet disappearing wind more real than I am. I was fifteen the last time I stood here, and unlike hers my face has changed. It’s changed a lot, beyond all recognition, and failing to recognize it as anyone alive here now, affectionate hands read my face briefly, gently, before she turns away and hurries on.

Subscribe to Pleiades to read the full “Celebration of Franz Wright,” featuring more unpublished poems by Franz Wright, more family photos, and more remembrances by family, friends, and fans.