Essays on Writers and Writing

American Sonnets: PolyVocality and Code Switching With Wanda Coleman and Terrance Hayes

by Mike Sonksen

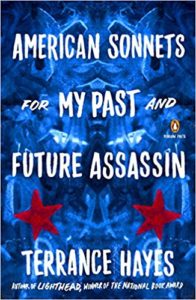

The recipient of both the National Book Award and MacArthur Genius Grant, Terrance Hayes is undoubtedly one of the most progressive Poets writing today. His latest book, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin recently published by Penguin Poets is more contemporary than tomorrow. Composed during the first six months of the Trump presidency, Hayes meditates on America’s past, present and future with deep insight, sarcasm and compassion in 70 American sonnets. (More on what makes an American Sonnet in a few paragraphs.).

Hayes’s American Sonnets masterfully disrupt form and riff with a tenor more relentless than a bullet train: “You are beautiful because of your sadness,” Hayes writes, “but / You would be more beautiful without your fear.” The book begins with three lines from the late great Los Angeles poet Wanda Coleman: “bring me / to where / my blood runs.”

Hayes credits Coleman and her three decade project of writing American Sonnets as the inspiration for his new collection. Though this essay will focus even more on Coleman, Terrance Hayes’s poetic prowess carries on her innovative spirit forcefully. Furthermore, they both code switch and change registers within their poems with profound dexterity.

Wanda Coleman’s lyrical register, like Terrance Hayes, is as versatile as it gets. Born Wanda Evans in Watts in the South-Central section of Los Angeles in 1946, Coleman published over 1,000 poems in 20 books of poetry, fiction and journalism while sharing stages with Jayne Cortez, Amiri Baraka, Ray Bradbury, Alice Coltrane, Charles Bukowski, the Watts Prophets, Allen Ginsberg, and many others. Not only is Coleman one of the most significant poets in Los Angeles lore, she is also among the most influential American voices of the second half of the 20th Century.

Her accomplishments are that much more meaningful because Coleman is an African-American woman that persevered in the face of racism, 4,500 rejection slips, two divorces and years as a single parent. To say Coleman paid her dues is an understatement. Though she died in November 2013, her legacy continues to grow. She was called the Unofficial Poet Laureate of Los Angeles, but she was much more than this. Coleman wrote about the real Los Angeles, not the false representation shown by Hollywood. She mapped L.A. through poetry and captured the voices of each neighborhood. I met Coleman in 2002 and interviewed her in 2003 and 2013 in addition to seeing her read live dozens of times. This account synthesizes excerpts from conversations with Coleman, her poetry and prose and thoughts from writers who knew her.

Terrance Hayes recently told me, “I think her reputation will grow exponentially in the coming years. More and more folks are going to realize she can’t be replaced. She was a walking legend.” As stated earlier, Hayes was especially influenced by Coleman’s 1994 book, American Sonnets.

Hayes is not the only prominent contemporary poet saluting Coleman. At a University of Southern California event in fall 2017 with 3 distinguished poet laureates: Juan Felipe Herrera, Dana Gioia and Robin Coste Lewis, Herrera and Lewis both read pieces dedicated to her.

The Cal Arts Professor and award-winning poet Douglas Kearney declares: “Wanda Coleman had a grip on the voices of Los Angeles. What I mean is that she could swing registers from block, to TV personality, to Sunset surrealist, to narrator, to late night/Sunday Morning/drive-time radio. Radio! Her work was like tuning a radio really quickly back and forth, letting it rest for a sec when it could pierce through the static. Signal in the noise and the noise as signal.” Kearney cites Coleman’s poetic command, her lyrical authority, a linguistic versatility he calls “polyvocality.” This polyvocality is especially apparent in her American Sonnets.

American Sonnets

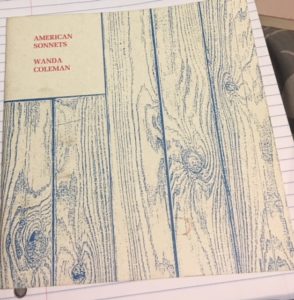

American Sonnets is a 1994 collection by Coleman that includes 24 sonnets. Co-published by Light and Dust Books and Woodland Patter Book Center, Coleman reinvents the sonnet making the form her own. Some of them are 14 lines, but they are not structured on the Petrarchan, Shakespearean or Spenserian form. In a 2008 interview with the Seattle poet, journalist and Founder of the Cascadia Poetry Festival, Paul Nelson, Coleman spoke extensively about her American Sonnets and how she created them. Coleman wrote 100 American Sonnets. Coleman’s American Sonnets are quintessential examples of her superior poetic craftsmanship and they are the subject of much discussion across the contemporary poetry scene.

Coleman numbered each American Sonnet she wrote. 1 through 24 were in the 1994 book of the same name, 26 through 86 were in her 1998 book BathWater Wine (Black Sparrow) and then 25 is published along with 87 through 100 in Coleman’s 2001 collection, Mercurochrome (Black Sparrow.) Both books were critically acclaimed. BathWater Wine received the 1999 Lenore Marshall Poetry prize from the Academy of American Poets and Mercurochrome was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2001. (Along with her 1983 book, Imagoes, these titles are considered her most iconic books of poetry.)

In his highly informative conversation with Coleman, Paul Nelson asks her about the series and how they came to be. Coleman told him, “The idea came to me when applying for an NEA grant in the early 70s. The application seemed to suggest that having a project, other than merely writing poems, was m ore likely to get a favorable response.” She also had just received some negative criticism/rejection from a literary magazine in the Midwest where the editor/publisher told her she was writing jazz poetry.

ore likely to get a favorable response.” She also had just received some negative criticism/rejection from a literary magazine in the Midwest where the editor/publisher told her she was writing jazz poetry.

“At the time” Coleman stated to Nelson, “I had no idea what he meant. How was jazz poetry distinct from any other poetry? I didn’t get the NEA on that go-round. I set the incidents aside; however, they apparently were at work in my deep consciousness, and a decade later the first sonnet appeared unbidden. I recognized it and they were off and running, coming at undetermined intervals.” She not only wrote the 100 labeled American Sonnets, she wrote a few others that appear in various books of hers like one she titled “Off Bonnet Sonnet,” and one she wrote for her longtime husband, “Sonnet for Austin.” Coleman explained to Nelson that her process included rereading Shakespeare’s sonnets over and over and then after digesting the form, she remixed it to make it more contemporary.

Coleman calls her American Sonnets “jazz poems” in different interviews and she describes their spirit further in the interview with Nelson: “Since jazz is an open form with certain properties–progression, improvisation, mimicry, etc., I decided that likewise the jazz sonnet would be as open as possible, adhering only to the loosely followed dictate of number of lines. I decided on 14 to 16 and to not exceed that, but to go absolutely bonkers within that constraint. I also give the sonnets a jazzified rhythm structure, akin to platter patter and/or scat and tones like certain Beat writers such as Kerouac, Kaufman and Perkoff. I decided to have fun–to blow my soul.”

Blowing her soul is indeed what Coleman’s jazz sonnets do. They are musical and spontaneous in so many ways. In 2004, Coleman signed a copy of American Sonnets for me at Skylight Books. I have read them again and again and after revisiting the jazz poetry of Bob Kaufman and Jack Kerouac, it is easy to see how the playful spirit within Coleman’s sonnets is like Kaufman and Kerouac. Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues shares a similar improvisational aesthetic.

The spontaneity and mix of registers within each of Coleman’s American Sonnets truly make the series a landmark cycle of poems. Douglas Kearney sees her American Sonnets as “masterful, clinics in polyvocality.” He cites four lines in “American Sonnet 91” as a perfect example of multiple registers within a few lines:

the gates of mercy slammed on the right foot.

they would not permit return and bent

a wing. there was no choice but

to learn to boogaloo.

Kearney writes further explaining: “How she moves from the mytho-epithetic ‘gates of mercy’ to a tragicomic image of someone trying to gain access in the first line. How in the next she seamlessly adopts the legal/officious language of ‘would not permit return’ to pivot on a skewed synecdoche for angels to end on vernacular? I mean, damn. I can just hear her, but perhaps more importantly, I can hear it. The sprawl of the city punched through with small meannesses, cruelties that drive one to make survival look like joy.” Kearney dedicated the final poem in his last book to Coleman and his own polyvocality pays tribute to her.

Terrance Hayes’s American Sonnets

As stated earlier, Coleman’s sonnets are so ripe with gravitas that Terrance Hayes wrote his own cycle of American Sonnets. Several of them have been published in the American Poetry Review, Poetry and the New Yo rker. Hayes first read Coleman in graduate school over two decades ago.

rker. Hayes first read Coleman in graduate school over two decades ago.

“But it was not until Bathwater Wine that I felt my eyes wobble,” he says. “Then came Mercurochrome! It’s a mind-blowing book. It blew my mind.” Hayes further praises Coleman for being “like a restless, curious mad scientist. The poems come in the forms of imitations, riffs, appraisals, songs. Her urgency was innovative. Also innovative: her emotional dexterity in the poems; her broad technical skills; her tempered wildness.”

Hayes’s cycle of American Sonnets began with one he wrote before Coleman passed that he sent to her titled, “American Sonnet for Wanda C.” In the piece Hayes states: “in her mouth the fingers of some calamity, / Somebody foolish enough to love her foolishly.”

Hayes explained the genesis of the series when he recently told me: “She came to me just before her birthday last November (She was born on November 13th). Trump was in office. I was among the many reeling, dizzy, hyperventilating. I wrote a couple of sonnets. And then I could hear Wanda’s American Sonnets blasting at America. I decided to title every sonnet I wrote thereafter ‘American Sonnet for My Past And Future Assassin.’” Hayes honors Coleman incredibly and carries on her incisive energy without missing a beat.

Hayes’s 70 American sonnets carry on Coleman’s polyvocality masterfully. Combining pop culture references, current political issues and American history with double entendres, puns, extended metaphors, interior rhyme and paronomasia, Hayes blows his poetic soul with the sophistication of Coleman. “I make you both gym & crow here,” he writes. “As the crow / You undergo a beautiful catharsis trapped one night / In the shadows of the gym. As the gym, the feel of crow- / Shit dropping to your floors is not unlike the stars / Falling from the pep rally posters on your walls.” Hayes’s American Sonnets was recently nominated for an National Book Award and rightfully so.

The Voice of Los Angeles

On the same night current Los Angeles Poet Laureate Robin Coste Lewis opened her set with one of Coleman’s poems, former United States Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera read his “Los Angeles Barrio Sonnet for Wanda Coleman.” Before reading the piece, Herrera spoke about meeting her shortly after the 1992 Rodney King Uprisings when they both read in Venice at Beyond Baroque.

Herrera’s “Barrio Sonnet,” is a truly moving elegy honoring Coleman. He lauds her as “Wanda Coleman word-caster of live coals of love.” Herrera’s impassioned reading of the piece quieted the capacity crowd to a whisper in USC’s Bovard Auditorium. Coleman would have appreciated that both the Los Angeles Poet Laureate and recent United States National Poet Laureate both paid tribute to her in their sets.

As stated in the Introduction, Coleman was called for decades, “the unofficial poet laureate of Los Angeles.” After many years of hard work with minimal recognition, Coleman did finally receive some long-deserved accolades, though not nearly enough. She earned Fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation as well as the 1999 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets and she was twice a finalist to be California Poet Laureate.

She also was the first literary artist to receive a grant from the City of Los Angeles’s Department ofCultural Affairs in 2003, but by the time the city started the Official Poet Laureate Program in 2012, Coleman no longer lived in L.A., having moved to the desert an hour and a half north east because the city was too expensive. Moreover, Coleman’s health was questionable, and she had retreated from public life around this time. Eloise Klein Healy was chosen as the first Los Angeles Poet Laureate in December that year and she was a solid selection — as a deeply engaged civic poet from the early 1970s on and a contemporary of Coleman’s from the early days of Beyond Baroque — nonetheless, though, Coleman deserved the honor more than anyone. Tragically of course, Coleman passed in November of 2013.

As much as she achieved, Coleman never did get her proper due in her lifetime. In 2003 she told me, “Ironically, some consider me part of the establishment. I guess that’s my reward for having toughed it out on this turf.” She represented Los Angeles from every angle during its darkest times from the Watts Riots, the Reagan years and into the 21st Century.

The award-winning former Los Angeles Times reporter Lynell George knew Coleman for three decades. George states: “Wanda wrote about L.A. in a way that you experience it if you push yourself out into it — in a dedicated, eyes-wide-open. Not that high-gloss L.A., but the L.A. so many of us live in and move through daily; one that so many people don’t see — even out of the corner of their eye. She made sure we saw and understood what struggle and love and loss and waiting and poverty looked like. People with dead-end 9-to-5 jobs, the people who were forever waiting for busses or breaks or a check.”

Recently many writers of all genres have emerged declaring that they write about the other Los Angeles, the city’s less glamorous side. Coleman did this from day one in the 1960s. And as much as writers like Charles Bukowski, Raymond Chandler, Carlos Bulosan and John Fante wrote about L.A.’s underworld, Coleman wrote about every side of the city: geographically, racially and socially. She captured everyday Los Angeles.

The Award-winning City Lights author Sesshu Foster characterizes her legacy: “Wanda was a force for Los Angeles, for literary L. A. and L.A. in general. She directly represented L.A.’s occasional harshness, its outspoken and out loud direct address, its nerve and feisty spirit.” Founder of the Friends of the Los Angeles River and esteemed poet Lewis MacAdams told me back in 2003, “Wanda is L.A.’s most popular poet, and Charles Bukowski’s true successor. No one could deny that.”

Sesshu Foster pontificates fondly on Coleman’s persona and her complexity. “Wanda could come off as flinty or irascible, both in print and in person,” he remembers. “Who else would get 86’d from Eso-Won Bookstore, Southern California’s prominent independent black bookstore for a scathing critique of Maya Angelou’s later work? Who else engendered so many fussy letters complaining about her column in the L.A. Times Magazine?” Terrance Hayes expresses a similar sentiment, “She could bite. Her love, like her truth-telling, was uncompromising. She was ferocious. No poet will come to match her poems or presence…”

Nonetheless, Foster concludes, “I suppose going in hard cost her jobs and friendships, but it was part of her integrity,” he says. “For younger writers like myself she was, more than some realized, a nurturing protective spirit. Through word of mouth, every now and then, I’d hear that Wanda had referred another of us for an award, a grant, a reading series. Editors and the hosts of reading series called. Wanda was looking out for us. Always, traveling to the East Coast for publication events and readings, you found out that Wanda had gone before, articulating the figure of L.A. sharpest in the larger imagination.”

Memorializing Coleman

In 2015 Coleman’s papers were preserved in the UCLA Library’s Special Collections Department. California poet and longtime research librarian Susan Anderson was an old friend of a Coleman and she authored the proposal that made this happen.

Coleman’s poetry is also incl uded in two of the latest anthologies of Los Angeles Poetry, 2015’s Wide Awake: Poets from Los Angeles & Beyond and 2016’s Coiled Serpent. Coleman is also a central poet in recent studies of Los Angeles Poetry like Bill Mohr’s Hold-Outs, Sophie Rachmuhl’s A Higher Form of Politics and Laurence Goldstein’s Poetry Los Angeles. Rachmuhl’s book also includes a DVD film with vintage 1980s footage of Coleman reading her work at a nightclub and talking about her writing process at home while holding a typewriter sitting on her bed. Filmmaker Bob Bryan’s nearly 90-minute documentary on Coleman from 2014 is also a rich source for information on her work and Tara Betts recently published a great poem about going out to lunch with Coleman in the anthology from Harriet Tubman Press, Voices of Leimert Park Redux.

uded in two of the latest anthologies of Los Angeles Poetry, 2015’s Wide Awake: Poets from Los Angeles & Beyond and 2016’s Coiled Serpent. Coleman is also a central poet in recent studies of Los Angeles Poetry like Bill Mohr’s Hold-Outs, Sophie Rachmuhl’s A Higher Form of Politics and Laurence Goldstein’s Poetry Los Angeles. Rachmuhl’s book also includes a DVD film with vintage 1980s footage of Coleman reading her work at a nightclub and talking about her writing process at home while holding a typewriter sitting on her bed. Filmmaker Bob Bryan’s nearly 90-minute documentary on Coleman from 2014 is also a rich source for information on her work and Tara Betts recently published a great poem about going out to lunch with Coleman in the anthology from Harriet Tubman Press, Voices of Leimert Park Redux.

In Venice Beach, there is a Poet’s Monument that includes words from 18 Los Angeles poets. Wanda Coleman’s words appear along with Charles Bukowski, Jim Morrison, Philomene Long, Ellyn Maybe and several others. The Ascot Branch Library in South L.A. near her childhood home was also recently dedicated to Coleman. These public memorials honoring Coleman are a step in the right direction towards honoring this epic scribe.

Douglas Kearney speaks for so many when he expresses beautifully Coleman’s polyvocality, sheer inventiveness and groundbreaking Los Angeles poetics. Kearney compares her to the prophetic Science Fiction scribe Octavia Butler. Kearney declares: “I guess I was hearing Wanda even when I was growing up in pre-Altadena® Altadena, because I heard it, the same way I learned to hear Octavia Butler through radio signals addled by foothills and driving one mile too far, or signage switching from Cyrillic, to Spanish, to English on the same bit of cruising. I’ve been chasing it. So, I’m following Wanda. I don’t know that I’ll ever catch up.”

Like Kearney, legions of contemporary poets are following Coleman. I know I am. On a personal note, I met Coleman in 2002 at Beyond Baroque and she was very kind. We exchanged dozens of emails over the years and she encouraged me with both my prose and poetry whenever we spoke. In addition to seeing her read dozens of times, I read with her at the Temple Bar in 2003, Skylight Books in 2004, Union Station in 2005, Beyond Baroque in 2011 and the Santa Cruz Poetry Festival in 2012. The last time I saw her was the night she featured at Cal State L.A. in May 2013. Earlier that day we spoke for over an hour as she reminisced about her lifetime in Poetry.

Coleman spent a lifeline paying dues. Though she won some awards and published 20 books, in many ways she did not receive the financial compensation or prestigious academic positions that many of her colleagues did, even if many of these writers did not publish or produce as much as she did. Nonetheless, Coleman’s work will continue to resonate for many more years, even though she is now gone.

In her poem, “Angel Baby Blues,” from her 1987 book, Heavy Daughter Blues she meditates on her years of struggle and finally earning her wings. The final lines of the piece capture her journey, deep struggle and the significance of earning her wings. These lines reveal her fortitude and desire for posterity. Coleman reminds us that no matter how hard it got being a poet in Los Angeles “I can’t give it up or give up on it it’s my birthplace it’s my pride my price having paid my dues forevah paying dues hopin’ to collect what’s due me// my wings.”

Despite that she may not have received professionally and monetarily all that she earned and deserved while alive, Coleman’s influence is ringing across America and transformative contemporary poets like Terrance Hayes and Douglas Kearney are celebrating her and carrying her groundbreaking poetics onward. It is these testimonies that show that Coleman’s poetic oeuvre did indeed accomplish all that she set out to do because the work is living on and resonating now more than ever. Coleman did indeed earn her wings.

Mike Sonksen is a 3rd-generation Los Angeles native. He has published over 500 essays and poems with publications and websites like the Academy of American Poets, KCET, Poets & Writers Magazine, BOOM, Wax Poetics, Southern California Quarterly, LA Weekly, Lana Turner, The Architect’s Newspaper, Los Angeles Review of Books, Cultural Weekly, Entropy, LA Taco and many others. Most recently, his essay on gentrification in South Central Los Angeles was Awarded for Excellence by the Los Angeles Press Club. He teaches at Woodbury University.