Revision Notes (Teaching Revision Part 7)

This is a continuation of my posts on teaching revision, specifically this one. If you’d like to contribute a guest post or response, please contact me at m [dot] salesses [at gmail etc.].

One of the things I’ve instituted in my courses because of other posts on this blog has been Revision Notes (sometimes I call them Writing Notes). My students record their writing/revision decisions continuously as they write/revise. They do this in a separate document from their manuscript. The idea for Revision Notes is a combination of a few other ideas from this blog, including an upcoming post from Susan Ito on the Critical Response Process, Lily Hoang’s workshop of the revision process, and my posts on recentering the workshop around the author, in which I asked a number of questions about how workshop might go differently in a more author-centered workshop. I decided to try answering of these questions when I ran my summer revision workshop. I started with three:

What would a workshop look like if everyone spoke as an author? If there was no one piece up for discussion, but all of them at the same time?

What would a workshop be like if everyone wrote a story from the same very specific prompt?

What would a workshop be like if the author submitted with her piece a list of decisions she made while writing it?

When I went to plan the course, these things seemed related. How can you workshop everyone’s piece all at once? If everyone started with the same prompt, you could talk about each person’s different approach. Then if you had Writing Notes from each author, you could talk about those different approaches in more detail, because you would have more access to them. It would be difficult to read 12 stories each week, but if people did it once and the class continued to check in on those stories’ progress via Revision Notes, we could talk about all of the pieces at once each time we talked about any single piece.

I’ve written about this course in earlier posts. I want to focus on the Notes now as a way to let the class into the writing process, and to make the workshop as much about process as about product. I also want to talk about the Notes as a way to approach craft as culture.

The other day I was talking to another writer of color in my program, and she mentioned that she didn’t think writing could be taught. I expressed surprise. Why be in a writing program then? When she saw my surprise she explained a little. She didn’t believe in craft (as she had been taught to use the term), and she thought that some revision methods could be taught, but not writing.

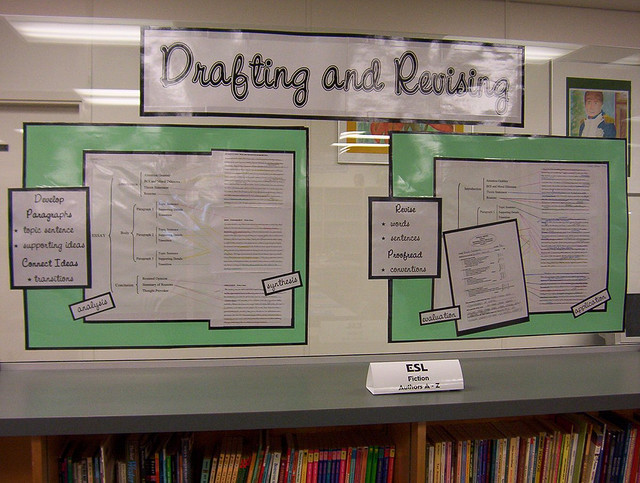

To me, most of writing is revision. What she seemed to be calling “writing” is what I would call “drafting”–first drafting–if there is to be a split between writing and revision. So to say that revision can be taught is, to me, to say that writing can be taught.

I could also empathize with her on the matter of craft. We’re often taught craft as some kind of consistent nuts & bolts, as if plot and arc and characterization and POV can be defined in only one way. I wrote about this when I was writing about how “pure craft” is a lie, but I think the answer is to acknowledge that craft is cultural. Not that it doesn’t exist, but that what we think of as plot is cultural, what we think of as arc is cultural, what we think of as characterization is cultural, and a different culture might view these elements of craft in completely different ways. To teach craft then is to teach culture, which often doesn’t get acknowledged in the classroom. It’s especially troublesome when you have other cultural ideas about what craft is and they get flattened or run over by a kind of (for lack of a better way of saying it) mainstream MFA cultural understanding of craft.

I think Revision Notes can help with these things. I’ll say more about how in the next post.